|

Although the diverse nature of vasculitis presents a diagnostic challenge, optometrists are up to the task. A careful patient history, ophthalmic testing and a systemic workup are integral to detecting and managing signs of this heterogeneous group of disorders that includes rare forms such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), also known as Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Vasculitis Essentials

The term vasculitis refers to a group of relatively uncommon conditions characterized by inflammation and damage in blood vessel walls, leading to tissue necrosis. Vasculitis has a reported annual incidence of 40 to 54 cases per one million persons and appears to vary with geographical location, patient age and seasonal changes.1

Blood vessels of any type, including capillaries, veins/venules and arteries/arterioles, can be affected, resulting in a broad spectrum of signs and symptoms. While vasculitis may be limited to the skin or other individual organs, it may also be a multisystem disorder with several manifestations and complications. There are 10 primary vasculitides based on vessel size (small, medium and large).1

|

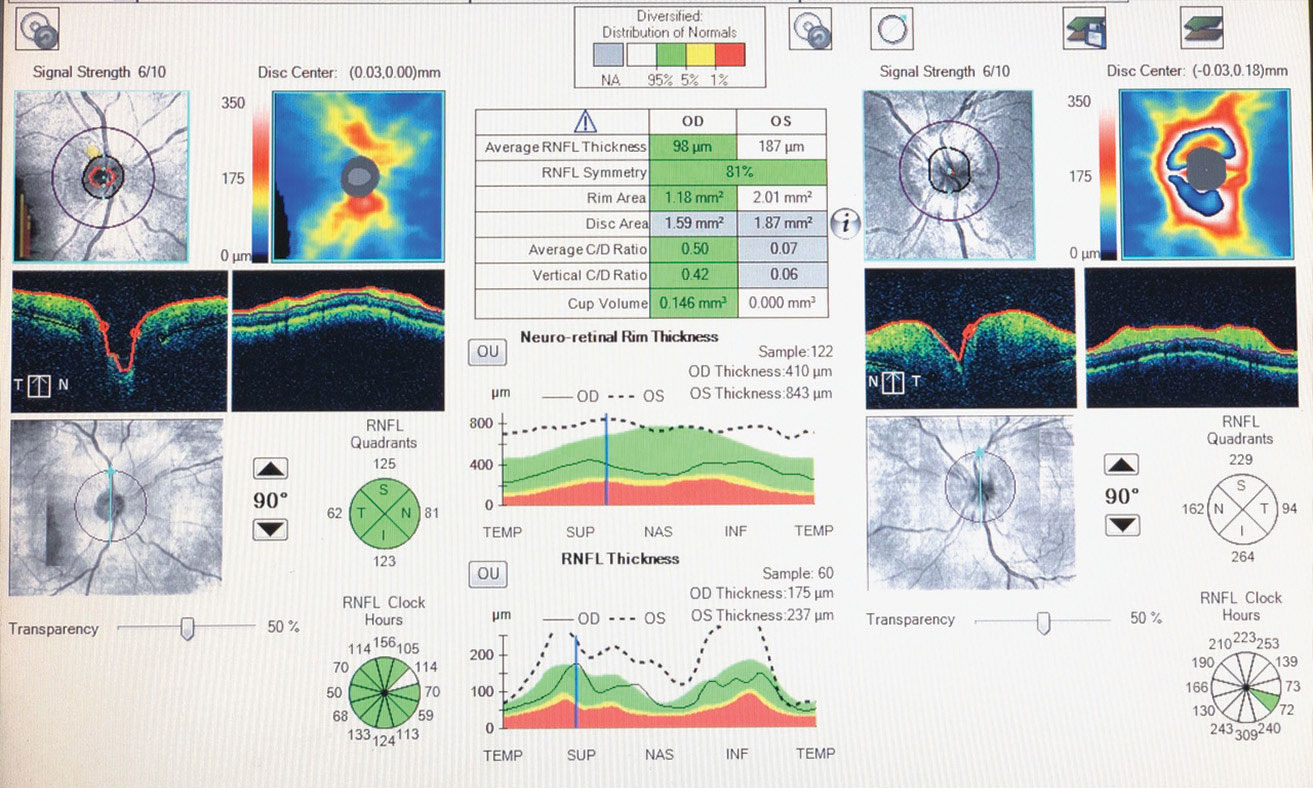

| Fig. 1. OCT of the left optic nerve the day this patient first presented with GPA reveals optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer edema. |

The ABCs of GPA

GPA is an inflammatory disease that affects multiple organ systems and is believed to be autoimmune in origin.

Although it can occur almost anywhere in the body, GPA most frequently impacts the kidneys and respiratory tract, and the associated vasculitis has a predilection for smaller arterial blood vessels. GPA most commonly occurs around the age of 50 and is equally common in males and females. It occurs in around five to 10 cases per million people every year.1,2

Because typical cases of GPA show renal or respiratory signs, patients commonly present with symptoms similar to pneumonia or a sinus infection. GPA may also cause generalized symptoms of fatigue, a low-grade fever and weight loss. The diagnosis is based on the results of blood tests, radiologic (x-ray and computed tomography) findings and a thorough physical exam. A biopsy of the affected tissue can help confirm the diagnosis when necessary. Lab results typically show elevated ESR and CRP, and elevated anti–neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) levels. ANCA testing with C-ANCA/PR-3 in particular shows high sensitivity and specificity for the disease.1,3

The prognosis in patients with GPA depends on when treatment starts and how much damage has already occurred at the time of diagnosis. It also varies depending on whether the GPA is C-ANCA or P-ANCA related, as higher levels of C-ANCA/PR-3 correlate with a higher mortality rate.1,3,4 A patient treated before any damage can occur may be able to achieve remission. However, if left untreated, the survival rate is one to two years.1,5

|

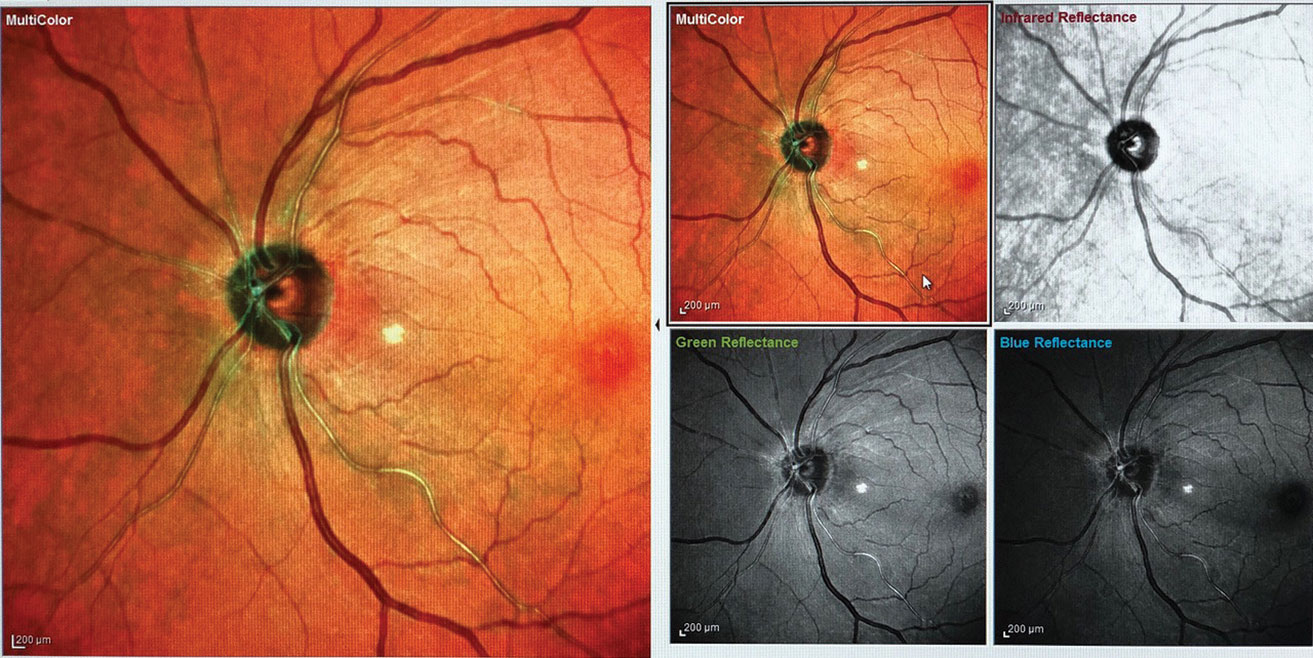

| Fig. 2. One month after initiating treatment, the patient’s disc edema and vasculitis have mostly resolved (the white spot temporal to the nerve is an artifact). |

The Eye in GPA

Ocular manifestations may be the presenting sign of GPA, as ocular involvement is between 29% and 79% in a patient’s lifetime.6 Findings are similar to those of other vasculitides and may include any of the following:4,6

- Blurred vision

- Necrotizing scleritis

- Uveitis (usually associated with the scleritis)

- Keratitis

- Retinitis

- Retinal vasculitis

- Optic nerve head edema and atrophy

- Orbital disease

- Visual field loss (defects correlate with optic neuropathy)

Case ReportA 59-year-old black female presented with complaints of hazy peripheral vision in her left eye for the past week that was constant and had been worsening. Her medical history was positive for diabetes mellitus type 2, depression and hypertension. Her medications included metformin, Celexa (citalopram, Allergan), acetaminophen/codeine, bumetanide and trazadone. She reported symptoms of mild fatigue, shortness of breath and mild coughing. Her visual acuities measured 20/20 OD and 20/20-2 OS. We documented a grade 1+ relative afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. Her confrontation fields showed mild generalized constriction in all four quadrants in the left eye. The dilated fundus exam revealed left optic disc edema with hemorrhage, a flat macula and arteriolar vasculitis. Threshold perimetry showed a mild superior rim defect in the right eye and a repeatable inferior and superior arcuate defect in the left eye, as well as an enlarged blind spot with slightly high fixation losses and high false positives. We took OCT and multimodal ophthalmic imaging (figures 1 and 2). Her lab results included several abnormalities:

Due to the high level of P-ANCA with MPO, increased ESR and CRP, inflammation of the optic nerve head, vasculitis in the retinal arterioles and pneumonitis-like symptoms, we made a tentative diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis and started the patient on a steroid pulse of 80mg PO QD. We communicated the results with her rheumatologist and cardiologist and scheduled follow up. One month later, we observed resolution of the optic nerve head edema and retinal vasculitis, although the visual field defect remains. Team-based care is ongoing. |

GPA Management

Treatment varies depending on the severity and the stage of the disease. GPA is categorized into two stages: the induction (or presentation) phase and the remission maintenance phase.

The presentation phase is further broken down into early systemic, generalized and severe stages, all of which are treated with immune suppressants and monoclonal antibodies.1 Pharmacotherapies and methods may include methotrexate, cyclophospomide, rituximab, corticosteroids and, if the presentation is severe, plasma exchange.1,7,8

The remission maintenance phase includes major relapse, refractory disease and maintenance therapy. Patients in any of these stages can be placed on intravenous immunoglobulin or different monoclonal antibodies and immune suppressants.1,8

A patient diagnosed with GPA should be managed by an interprofessional team that includes ODs. As vital members of that team, optometrists can be involved with every step of the process from diagnosis to treatment and comanagement. GPA is serious but treatable and requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent complications.

Dr. Zuercher is a 2018 alumna of University of the Incarnate Word Rosenberg School of Optometry, where she is now a resident in primary care optometry.

1. Sharma P, Sharma S, Baltaro R, Hurley J. Systemic vasculitis. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(5):556-65. 2. Pakrou N, Selva D, Leibovitch FI. Wegener’s granulomatosis: ophthalmic manifestations and management. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;35(5):284-92. 3. Salehi A, Kianersi F, Ghanbari H, et al. Simultaneous unilateral presentation of three different ocular manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Ophthal Vis Research. 2018;13(2):203-6. 4. Taylor S, Salama A, Pusey C, Lightman S. Ocular manifestations of Wegener’s Granulomatosis. Exp Rev Ophthalmol. 2007;2(1):91-103. 5. Heitkotter B, Kuhnen C, Schmidt S, Wittchieber D. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis): a rare variant of sudden natural death. Internat J Legal Med. 2018;132:243-8. 6. El-Asrar A, Herbort C, Tabbara, K. Differential diagnosis of retinal vasculitis. Middle East African J Ophthalmol. 2009;16(4):202-18. 7. Drooger JC, Dees A, Swaak AJG. ANCA-positive patients: the influence of PR-3 and MPO antibodies on survival rate and the association with clinical and laboratory characteristics. Open Rheumatol J. 2009;3:14-17. 8. Tarzi R, Pusey C. Current and future prospects in the management of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2014;10:279-93. |