|

A woman presents with a history of floaters and a slight decrease in vision in her left eye. She reports mild ocular discomfort, but no photophobia. She says that she has never previously experienced a decrease in vision and ocular discomfort.

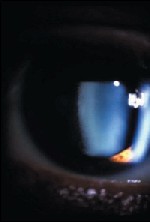

Biomicroscopically there is a granulomatous reaction with mutton-fat keratic precipitates. There is extensive posterior synechiae and a very heavy anterior chamber cell and flare response. Her visual acuity in the affected left eye is 20/60, and her IOP is 3mm Hg.

|

|

|

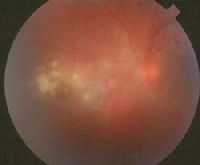

Left: Note the active toxoplasmosis lesion adjacent to a toxoplasmosis chorioretinal scar. (This photo was taken of a different patient than the one mentioned in this column.) Photo courtesy: Barry Frauens, O.D. Right: The left eye of a 37-year-old patient with active toxoplasmosis. Note the floating spots. Photo courtesy Andrew S. Gurwood, O.D. |

What seemed like a straightforward case of anterior uveitis has revealed itself to really be a spillover from a toxoplasmosis chorioretinitisthe topic of this months column.

Toxoplasmosis Background

Toxoplasmosis is caused by the obligate intracellular protozoan Toxoplasma gondii. The most common intermediate host is a cat. Toxoplasmosis is one of the most frequent causes of retinochoroiditis in humans.1 Exposure to this condition is very common, with 60% to 80% of studied populations possessing some seropositive findings.2-4

The systemic symptoms found in congenital toxoplasmosis consist of convulsions, calcification of the arterioles and chorioretinitis.5 In adults, toxoplasmosis is often contracted without sickness.1,6 A small percentage of individuals encounter self-limiting, flu-like symptoms at the time of inoculation.1,6

Toxoplasma exists in humans in two forms: actively motile tachyzoites and encysted bradyzoites. The oocysts, which contain the organisms that produce infection, are excreted in fecal material and may lie dormant in the soil until ingested by other animals. This results in infection.5

There are three modes of toxoplasma transmission: oral intake of raw or undercooked meat or contaminated fruits and vegetables, ingestion of materials contaminated with cat feces, and transplacental infection.6 Toxoplasmosis can only be transmitted to a fetus during maternal parastemia.1,6 Congenital toxoplasmosis accounts for the majority of cases encountered in clinical practice.1,6

In most cases, the body is primed for infection or toxoplasmosis reactivation by an immune system failure.5 This may occur following contraction of human immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV) or with medical immunosupression following organ transplantation. In immunocompetent individuals, toxoplasmosis chorioretinitis is a self-limiting disease.

The symptoms associated with ocular toxoplasmosis include unilateral, mild ocular pain, blurred vision and new onset of floaters. Clinical findings may include granulomatous anterior chamber reaction, vitritis, optic disc swelling, neuroretinitis, vasculitis and retinal vein occlusion in the vicinity of the inflammation. Active toxoplasmosis presents with white-yellow, chorioretinal lesions and vitreous cells.6 Often, the active lesion is adjacent to an area of chorioretinal scarring, as in the above case.

Management

The goal of management is two-fold: eradicate the parasite and suppress the inflammatory response. Many practitioners utilize the antibiotic oral sulfadiazine 2 to 4 grams/day, in divided doses, for four to six weeks to accomplish these tasks. Bactrim DS (trimethoprim 160mg/sulfamethoxazole, Roche) 800mg 1 tab p.o. b.i.d. for four to six weeks is also most commonly prescribed. An alternate treatment is pyrimethamine (a 75mg loading dose, followed by 25mg p.o. b.i.d. ) with sulfadiazine (2g loading dose, then 1g p.o. q.i.d. for four to six weeks). Both medications inhibit the folic acid metabolism necessary for toxoplasmosis to survive. Concurrent folic acid, 3mg to 5mg p.o. twice weekly helps to minimize any bone marrow toxicity produced by the pyrimethamine.

After beginning antibiotic therapy in immunocompetent individuals, oral prednisone at a dose of 20mg to 80mg daily for four to six weeks can be added to help suppress the remaining inflammation. However, oral steroids without systemic antibiotics are expressly contraindicated.

The Question of Treatment

While we have long known how to treat toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis, we dont know if we should treat this disease. Despite current clinical practices in which medication is used to treat active toxoplasmosis infections, especially if the lesion threatens the optic nerve or macula, there is a lack of evidence to support routine antibiotic treatment for acute toxoplasma chorioretinitis in terms of improving the outcome of the disease.7,8 Clearly, controlled studies need to be performed to determine the effectiveness of antibiotic treatment in immunocompetent individuals.

What we do know is that for individuals with recurrent toxoplasmosis chorioretinitis, long-term intermittent treatment (one tablet of Bactrim DS every 3 days) significantly reduces the rate of recurrent Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis.9 Therefore, this treatment must strongly be considered in patients who have recurrent disease.

Once properly diagnosed with toxoplasmosis, the patient mentioned above was treated with Bactrim DS and responded well.

Drs. Sowka and Kabat are members of Alcons speakers alliance. They have no financial interest in any of the products mentioned. Special thanks to Maryke Neiberg, O.D., for her assistance with this months column.

1. Balayre S, Gomez K, Tribut A, et al. Toxoplasma gondii and necrotizing retinitis: a case report. J Fr Ophtalmol 2003 Oct;26(8):837-41.

2. Varella IS, Wagner MB, Darela AC, et al. Seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2003 Jan-Feb;79(1):69-74.

3. Pawlowski ZS. Toxoplasmosis in Poznan region, Poland 1990-2000. Przegl Epidemiol 2002;56(3):409-17.

4. Bahia-Oliveira LM, Jones JL, Azevedo-Silva J, et al. Highly endemic, waterborne toxoplasmosis in north Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2003 9(1):55-62.

5. Martin S. Congenital toxoplasmosis. Neonatal Netw 2001 Jun;20(4):23-30. 6. Atmaca LS, Simsek T, Batioglu F. Clinical features and prognosis in ocular toxoplasmosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2004 Jul-Aug;48(4):386-91.

7. Stanford MR, See SE, Jones LV, et al. Antibiotics for toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis: an evidence-based systematic review. Ophthalmology 2003 May;110(5):926-31.

8. Gilbert RE, See SE, Jones LV, et al. Antibiotics versus control for toxoplasma retinochoroiditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1):CD002218.

9. Silveira C, Belfort R Jr, Muccioli C, et al. The effect of long-term intermittent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole treatment on recurrences of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol 2002 Jul;134(1):41-6.