|

A 49-year-old Hispanic female presented for a second opinion regarding chronic floaters and photopsia OU for seven months that were previously diagnosed as a posterior vitreous detachment. Medical history included migraines and hypothyroidism that were both controlled medically. She had no personal or family history of prior ophthalmic conditions.

Her entering VA was 20/20 OU, IOP was 12mm Hg OU, confrontation visual fields and extraocular motilities were full and pupils were equally round without a relative afferent pupillary defect. Slit lamp exam revealed a 1+ anterior and posterior subcapsular cataract OS and 1+ anterior and posterior vitreous cell OU.

Take the Retina Quiz

1. Which is true regarding the imaging?

a. There is retinal vasculitis on the fluorescein angiogram.

b. There is diffuse choroidal infiltration on the indocyanine green angiogram.

c. There are fine vitreous opacities though no cystoid macular edema on the OCT.

d. All of the above are true.

2. What is the most likely diagnosis?

a. Behçet disease.

b. Birdshot chorioretinitis.

c. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma.

d. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease.

3. Which is a known human leukocyte antigen associated with this condition?

a. HLA-A29.

b. HLA-B27.

c. HLA-B51.

d. HLA-DR4.

4. Which of the following is not a typical etiology for decreased vision in this disease?

a. Cataract.

b. Cystoid macular edema.

c. Exudative retinal detachment.

d. Retinal damage and photoreceptor loss.

5. What is the appropriate treatment?

a. Medrol Dosepak.

b. Pars plana vitrectomy.

c. Topical prednisolone acetate one drop four times daily tapered weekly.

d. Oral prednisone with early immunomodulatory therapy induction.

|

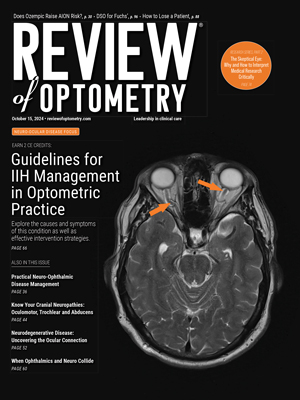

Fig. 1. Optos fundus photo OD (left) and OS (right). Click image to enlarge. |

|

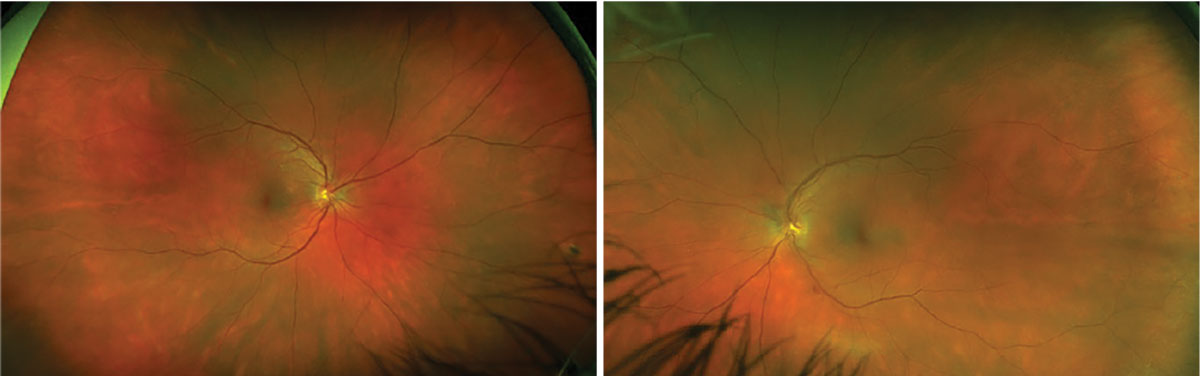

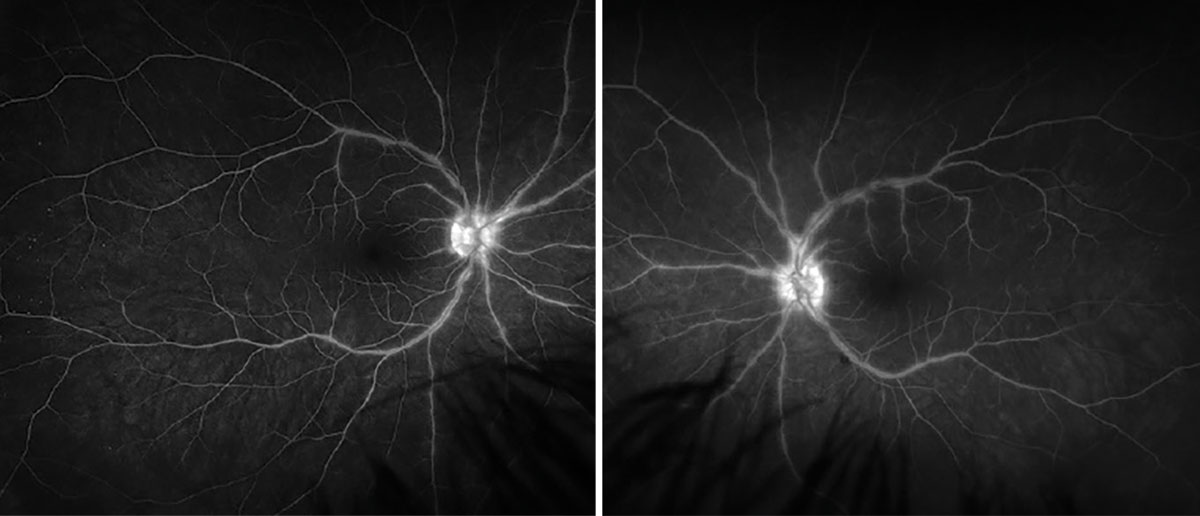

Fig. 2. Optos FA OD (left) and OS (right). Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

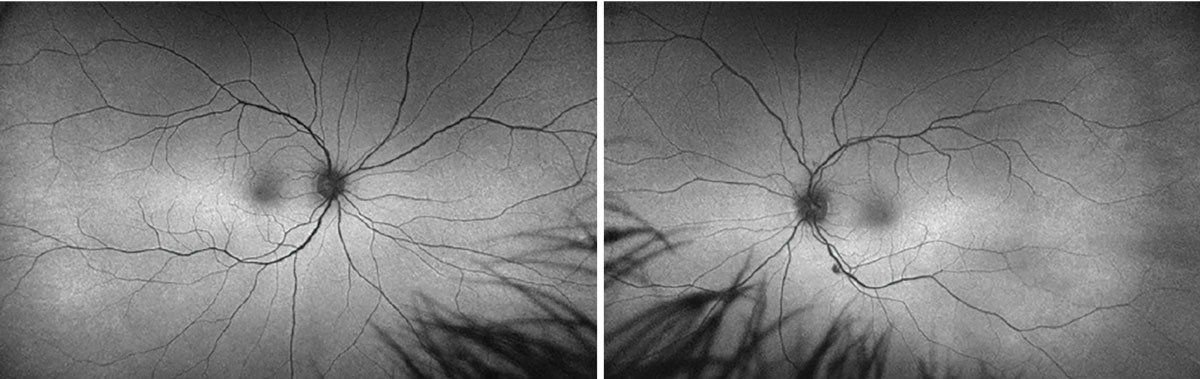

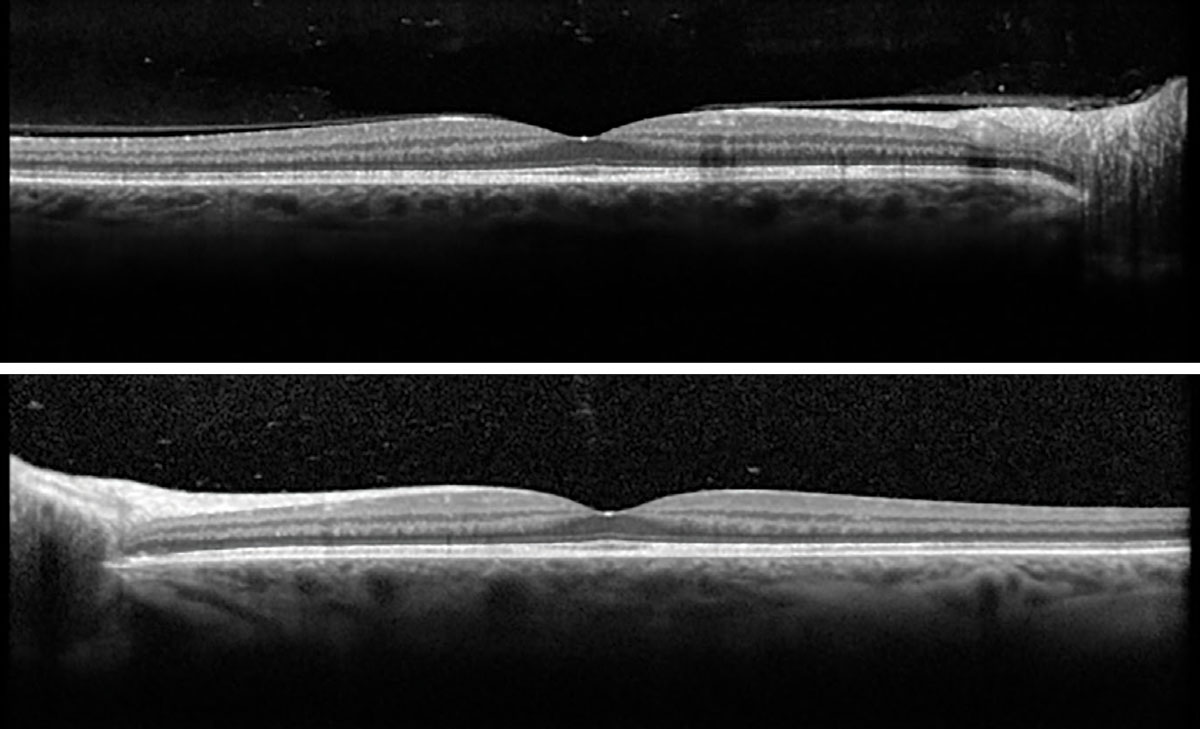

Fundus exam revealed subtle diffuse, creamy, ovoid choroidal lesions distributed throughout the fundus OU, vascular tortuosity OU, chorioretinal scar nasally OD and an intraretinal hemorrhage inferotemporal to the optic disc OS. (Figure 1). Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) showed hypoautofluorescence corresponding with the intraretinal hemorrhage with otherwise no abnormal hyper- or hypoautofluorescence (Figure 2). OCT showed the macula was flat without fluid or lesions; the hyaloid was attached OD, and there were a few scattered vitreous opacities OU (Figure 3). Fluorescein angiography (FA) showed large vessel venous leakage OU, and the indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) late phase showed diffuse hypocyanescent lesions distributed throughout the choroid OU (Figures 4 and 5). Suspicion was highest for birdshot chorioretinitis based on clinical exam and ICGA. Serologies ruled out infectious etiologies and the diagnosis was confirmed with positive HLA-A29.

|

Fig. 3. Macular OCT OD (top) and OS (bottom). Click image to enlarge. |

Birdshot chorioretinitis is a chronic, bilateral, non-infectious posterior uveitis with a typical phenotype of diffuse creamy choroidal lesions that are classically most prominent inferonasally.1,2 It was first described as “birdshot” in 1980 based on the distinct appearance and distribution of the lesions; the following year, the term “vitiliginous chorioretinitis” described the resemblance of the choroidal depigmentation to that of vitiligo.2-4 Birdshot chorioretinitis has an estimated prevalence of less than one in 100,000 and accounts for 1% of all uveitides and 7% of all posterior uveitides.1,2,5,6 It is seen most frequently in Caucasians in the sixth decade of life with a slight female predominance.1,2,6

|

|

Fig. 4. Late-phase FA OD (left) and OS (right). Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnostic Criteria

Ones from the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature working group include: 1) characteristic bilateral multifocal choroiditis (“birdshot spots”) on ophthalmoscopy, 2) mild to no anterior chamber cell in the absence of keratic precipitates and posterior synechiae, 3) moderate to no vitritis or 4) +HLA-A29 in the setting of either characteristic “birdshot” lesions or characteristic hypocyanescent lesions on ICGA.6 The presence of criteria one through three or four alone are sufficient to make a diagnosis. Exclusions include positive serologies for syphilis, evidence of sarcoidosis (radiographic or tissue biopsy) or intraocular lymphoma.6

HLA-A29 positivity is nearly diagnostic in the appropriate clinical setting as it is present in nearly all patients with birdshot chorioretinitis.1,5 The association is so strong that authors have regarded HLA-A29 positivity as a “sine qua non” (i.e., without which, not) criterion for the diagnosis of birdshot chorioretinitis; thus, in patients with a negative HLA-A29, alternative diagnoses (including malignancy) must be thoroughly excluded.2 HLA-A29 is present in approximately two to three in 10,000 of the general population, 7% to 9% in all Caucasians and >95% of all birdshot chorioretinitis patients.2,6,7

Approximately 97.5% of patients are symptomatic to floaters, photopsia, blurry central vision, loss of peripheral vision, impaired contrast sensitivity or nyctalopia at time of diagnosis.6,8 Vision loss is usually due to cystoid macular edema (CME) or retinal damage with photoreceptor damage.6 Clinical exam shows creamy ovoid lesions disbursed throughout the fundus with inferonasal predominance.1,2,6

Multimodal Imaging

OCT is useful for the diagnosis and monitoring of CME as well as photoreceptor integrity.2 FAF is of little value in the diagnosis of early disease state, but can help monitor the status of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) (which portends photoreceptor health) in the later stages of disease.2 FA is useful in the diagnosis and monitoring of retinal vasculitis but is of little utility in the assessment of the choroidal lesions.2

ICGA is perhaps the most helpful imaging modality to demonstrate the presence of choroidal lesions as diffuse multifocal hypocyanescence, especially in early presentations where the lesions may be difficult to discern ophthalmoscopically due to subtlety or pigmentary fundus alterations (blonde fundus, chronic inflammation, etc.).2

Treatment

Initial management consists of systemic (with or without local) corticosteroids and early induction of corticosteroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapy (IMT) due to the incomplete response of birdshot chorioretinitis to corticosteroid monotherapy.9

Birdshot chorioretinitis generally requires long-term extended IMT to maintain suppression of intraocular inflammation and therefore preservation of vision.9 IMT may include the use of azathioprine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil and more recently adalimumab (tumor necrosis factor [TNF]- α inhibitor).2,9

Biologic agents such as adalimumab have a more favorable side effect profile than conventional immunosuppression and have demonstrated efficacy at controlling disease activity in both primary and refractory cases.2,9 Local therapies (sub-Tenon triamcinolone acetonide, intravitreal dexamethasone implant, intravitreal fluocinolone acetonide implant) are used in patients where systemic treatment is either intolerable or insufficient, though they carry a higher risk of cataract and glaucoma.2,9

Prognosis

Preservation of the choroidal pigment is necessary to maintain normal function of the overlying RPE and photoreceptors.8 Long-term visual prognosis depends on extent of choroidal infiltration; literature reports that 14% to 16% and 20% to 22% of patients will be legally blind (20/200 or worse in both eyes) at five- and 10-year follow-ups, respectively, as compared with 4% in the general uveitis population.7 Furthermore, 57% of patients achieve VA of 20/60 or worse, compared with 35% in the general uveitis population; the leading cause of vision loss in these patients is CME which is seen in 50% to 84%, compared with 30% in the general uveitis population.7

Once serologies ruled out infectious etiologies, our patient was started on oral prednisone 60mg daily and recommended early induction of IMT. She was resistant to initiating IMT due to concern for side effects and frequently self-discontinued her methotrexate initially and adalimumab later. Ultimately, adequate disease control was obtained with a combination of oral steroids, temporary use of IMT and local therapy with sub-Tenon triamcinolone acetonide. Her cataract OS eventually worsened and she underwent surgery. Her BCVA remains 20/20 OU, and she is being followed closely for any sign of disease reactivation with multimodal imaging.

Retina Quiz Answers

1: d, 2: b, 3: a, 4: c, 5: d

Dr. Aboumourad currently practices at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. He has no financial disclosures.

1. Cunningham ET, Levinson RD, Denniston AK, et al. Birdshot chorioretinopathy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2017;25(5):589-93. 2. Bousquet E, Duraffour P, Debillon L, et al. Birdshot chorioretinopathy: a review. J Clin Med. 2022;11(16). 3. Ryan SJ, Maumenee AE. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89(1):31-45. 4. Gass JD. Vitiliginous chorioretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(10):1778-87. 5. Jabs DA, Berkenstock MK, Altaweel MM, et al. The conundrum of clinical trials for the uveitides: appropriate outcome measures for one treatment used in several diseases. Epidemiol Rev. 2022;44(1):2-16. 6. Classification criteria for birdshot chorioretinitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;228:65-71. 7. Rothova A, Berendschot TT, Probst K, et al. Birdshot chorioretinopathy: long-term manifestations and visual prognosis. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(5):954-9. 8. Monnet D, Brézin AP, Holland GN, et al. Longitudinal cohort study of patients with birdshot chorioretinopathy. I. Baseline clinical characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(1):135-42. 9. Kiss S, Ahmed M, Letko E, Foster CS. Long-term follow-up of patients with birdshot retinochoroidopathy treated with corticosteroid-sparing systemic immunomodulatory therapy. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(6):1066-71. |