A 52-year-old white female initially presented in May 2000 as a new patient to the office. Her past ocular history was positive for ocular hypertension, for which she was monitored for approximately six years without intervention. She has no known history of glaucoma. Current medications include only Nexium (esomeprazole, AstraZeneca) qd. She underwent a cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal) three years earlier. Otherwise, her past medical history was unremarkable.

Best-corrected visual acuity has remained 20/20 O.U. through myopic astigmatic presbyopic correction since her initial presentation. Pupils are equal, round and 3+ reactive to light and accommodation, with no afferent pupillary defect.

The slit lamp examination of her anterior segments O.U. was completely unremarkable at all visits. When we first examined her in 2000, entering IOPs were 21mm Hg O.D. and 24mm Hg O.S. at 11 a.m. Her previous records indicated that IOP in the right eye ranged from a low of 17mm Hg to a high of 26mm Hg. IOP in the left ranged from 20mm Hg to 25mm Hg.

Gonioscopic examination demonstrated 360 open angles with ciliary body visible in all quadrants. There was a mild to moderate amount of pigment in the angles, and no angle abnormalities.

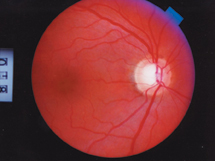

Threshold visual fields from 1995 through 2000when her previous provider last saw herremained normal and stable. There was no evidence of early glaucomatous visual field loss in either eye. Her neuroretinal rims were healthy, plush and well perfused, without thinning, nerve fiber layer defects, peripapillary atrophy or peripapillary vascular compromise.

This ocular hypertensive patient has a healthy-looking fundus.

Her condition was straightforward, so I chose to continue monitoring her in lieu of therapeutic intervention. Since I began seeing this patient, her visual fields have remained constant in both eyes, although she may be exhibiting a slight decrease in her overall threshold (standard deviation) in her right eye. The neuroretinal rims in both eyes have also remained stable. So has her gonioscopic appearance. Applanation tensions have averaged 22mm Hg O.D. and 24mm Hg O.S.

The recently published five-year results of the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study prompted us to obtain central corneal thickness (CCT) readings at her last visit. Her average pachymetry ranges were 525m O.D. and 517m O.S.

Discussion

When it was initially designed, many expected the OHTS study to provide results to take some of the guesswork out of managing patients with ocular hypertension. To a degree, this has happened: We can now be more comfortable with medical intervention for those hypertensives who have certain risk factors.1 On the other hand, the OHTS study has added another factor to evaluate in assessing riskcentral corneal thickness.

We have known for a while now that thinner corneas result in artificially low IOP readings. Independent of other risk factors (age, race, etc.), the OHTS data clearly show that as CCT decreases, the number of patients who convert to glaucoma increases. Note that the OHTS study does not establish a cause-and-effect relationship between the two risk factors; rather, it implies that low CCT has a masking effect on evaluating IOP. And that difference is magnified in patients with thin corneas and IOPs greater than 25-26mm Hg.

The OHTS study therefore makes the argument that CCT measurements should be included in the workup of glaucoma suspects. (See chart on next page.) Does this mean that you should go out and purchase a pachymeter? Perhaps. Some authors have gone so far as to say that the standard of care in managing glaucoma patients should include pachymetry. Nevertheless, you can certainly diagnose glaucoma without a pachymeter.

The OHTS data clearly show that as central corneal thickness (CCT) decreases, the risk for developing glaucoma increases. Specifically, the percentage of ocular hypertensives who develop glaucoma increases significantly when IOP is greater than 25.75mm Hg and CCT is less than 555m. Of the nine sub-groups evaluated (stratifying three IOP ranges and three CCT ranges), about one-third of ocular hypertensives whose IOP is greater than 25.75mm Hg and whose CCT is less than 555m will go on to convert to glaucoma.

The pachymeter is a convenient instrument to have in the office. But if you dont have one, will you underdiagnose glaucoma in patients with thinner corneas? That is certainly possible if you tend to emphasize IOP measurements in making the diagnosis. But if you consider IOP as one risk factor, along with neuroretinal rim characteristics, peripapillary atrophy, perioptic vasculature, age, race, family history, etc., then youll reduce the likelihood to underdiagnose.

Conversely, the likelihood to over-diagnose glaucoma exists if you rely too heavily on a thinner CCT measurement without taking into account other risk factors. The OHTS study does not give us a cookbook approach to making a diagnosis of glaucoma; it simply highlights another piece of the complex puzzle that we should consider in making that diagnosis; namely, central corneal thickness.

As for evaluating our patients IOP and corneal thickness, she has a 17% O.D. and 12% O.S. likelihood of converting to glaucoma, according to the OHTS results, if her IOP remains constant. Should her IOP rise consistently above 25-26mm Hg, then her likelihood increases to 36%. After discussing this information with the patient, we have jointly elected to continue monitoring her for now. Be aware, though, that this treatment plan has been established specifically for this patient. Other patients with other risk factors must be individually evaluated.

(For more on evaluating central corneal thickness with pachymetry, see Why Pachymetry? Why Now? in this issue.)

1. Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002 Jun;120(6):714-20.