Eyelids & Ocular SurfaceThe November 2024 Review of Optometry issue showcases five articles on eyelid & ocular surface conditions, from MGD to scleritis. Read about what to do when dry eye patients aren’t responding to treatment, corneal AEs caused by systemic meds, innovative MGD treatments, managing ocular cellulitis and more. Check out the other articles featured in this issue: |

Preseptal cellulitis, also known as periorbital cellulitis, is an infection that affects the skin and soft tissues around the eyes. Symptoms include localized redness (erythema), swelling (edema) and discomfort or pain in the affected area.1-3 This condition generally occurs secondary to a bacterial infection that remains anterior to the orbital septum. Fortunately, serious complications resulting from preseptal cellulitis are relatively uncommon, as the condition is often manageable with appropriate topical and oral treatments.1-3

Drug-induced iatrogenic deposits are often asymptomatic but can cause visible opacities that typically affect specific layers or regions of the cornea. Although meds may reach the cornea via tears, aqueous humor or perilimbal vasculature, the exact pathophysiology and mechanisms behind layer-specific deposits remain poorly understood.1 While some deposits are well-documented in the literature, others are scarcely mentioned in case reports.

Nonetheless, there are significant risks if it is misdiagnosed or inadequately treated. Inaccurate diagnosis or delayed treatment can allow the infection to progress to orbital cellulitis, a more severe and potentially dangerous condition. Orbital cellulitis will not only threaten vision; in extreme cases, it can pose life-threatening risks.1-3 Therefore, it is crucial for preseptal cellulitis to be accurately identified and effectively managed to prevent such adverse outcomes.

The differentiation between preseptal cellulitis and orbital cellulitis can be quite challenging, as both conditions present with similar symptoms, such as eyelid swelling and redness. However, the crucial factor that distinguishes these two is the location of the infectious process in relation to the orbital septum. Preseptal cellulitis occurs anterior to the orbital septum, involving the skin and soft tissues of the eyelid, while orbital cellulitis occurs posterior to the orbital septum, affecting deeper structures within the orbit.1-3

This anatomical distinction is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment. In addition to the general symptoms shared by both conditions, orbital cellulitis will present with more specific signs of orbital involvement. These may include exophthalmos (protrusion of the eye), reduced vision, swelling of the optic nerve, restriction of the extraocular muscles, orbital pain or an afferent pupillary defect. Furthermore, patients with orbital cellulitis might also exhibit systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise, which can help differentiate it from preseptal cellulitis and indicate a more severe infection requiring prompt medical intervention.1-3

Preseptal Cellulitis

This condition often develops as a secondary complication arising after an initial insult in and around the lid. The onset of symptoms following a hordeolum, an insect bite, an eyelid laceration or other skin infections, particularly when accompanied by a lack of visual changes, is indicative of a preseptal infection.1

The most frequent triggers for preseptal cellulitis include sinusitis, which can lead to the infection spreading to the surrounding tissues; insect bites, which may introduce bacteria into the eyelid area; periocular or facial trauma, which can create openings in the skin through which infections can enter; and impetigo, a highly contagious bacterial skin infection that can affect the facial and eyelid regions.1 Each of these inciting events can cause localized infection and inflammation in the tissues anterior to the orbital septum.

While these conditions often present with redness, swelling and discomfort, they typically do not involve visual disturbances or deeper orbital symptoms.1 When first evaluating a patient with suspected preseptal cellulitis, a provider should collect a careful history to include a history of previous insect bite, prior bump or rash or redness around the eyelid or trauma to the eye. Collecting a detailed medical history is also important, specifically to inquire about any immunocompromised or diabetic status, which affects treatment and diagnosis.

It is important to correctly diagnose patients. While physical examination will provide the majority of information needed, a thorough case history can aid in diagnosis. Questions regarding symptoms of vision loss and/or double vision, recent insect bites, trauma, dental work and prior infection can help with the diagnosis.1 Preseptal cellulitis will present involving one eyelid with diffuse erythema and edema along with pain and warmth to the touch. Other conditions that can masquerade as it are mild orbital cellulitis, hordeola, as well as swelling from viral infections such as herpes simplex or varicella zoster and localized edema from an allergic reaction.

Patients with hordeola will typically have a localized nodule and area surrounding either the adjacent meibomian glands and/or eyelash follicle that are inflamed. Varicella zoster will present with a rash and/or vesicles of the face or scalp on the same side as the edematous eyelid.

|

|

Preseptal cellulitis with eyelid erythema and edema in a patient with no ocular complications. Photos: Paul C. Ajamian, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Allergic reactions tend to have a more diffuse, water-filled appearance, with erythema. There will be a lack of pain and may present with scaling of the periorbital skin. Patients often are able to describe what elicited the allergic response, and those with both viral and allergic conjunctivitis will also have swollen eyelids and present with conjunctival edema, injection, discharge and swollen eyelids of both eyes. In contrast to these conditions, preseptal cellulitis involves only one eyelid and feel warm to the touch.

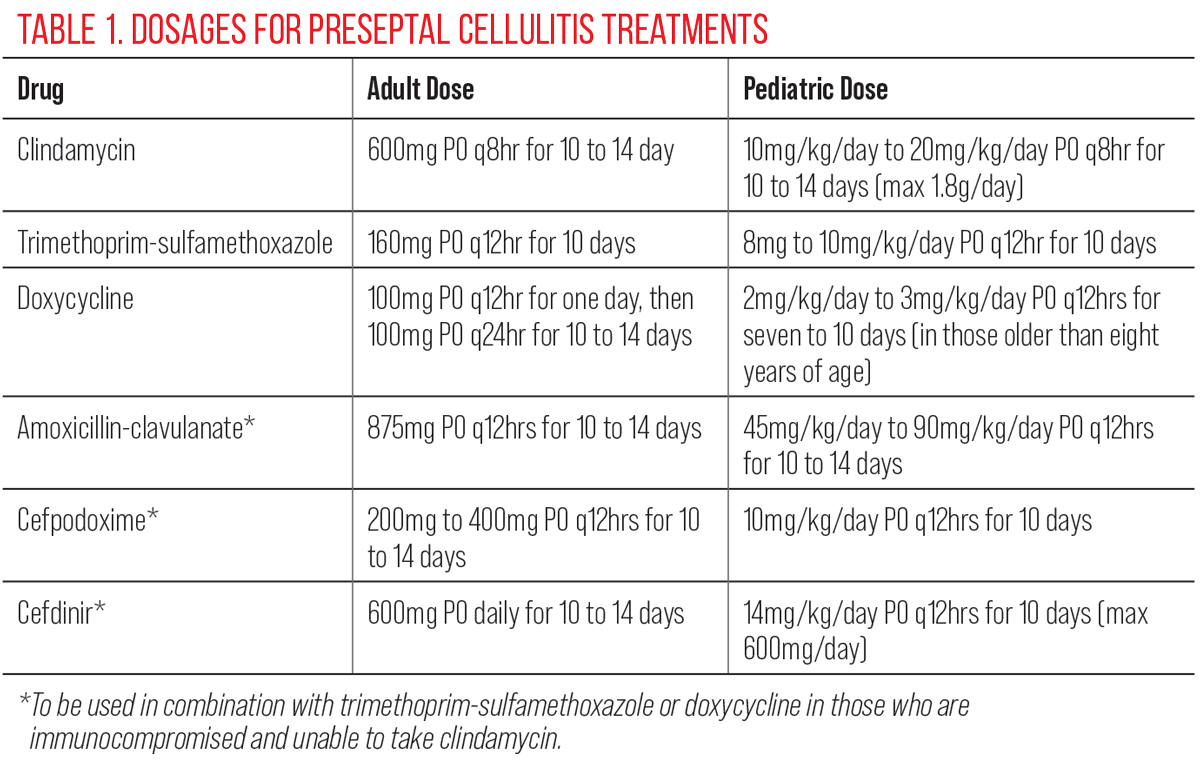

Management. The best treatment for preseptal cellulitis is prompt initiation of oral antibiotics. The most common pathogens are gram-positive Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Due to an increase in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), clindamycin is preferred. However, this poorly covers against Haemophilus influenzae, an uncommon source of infection in preseptal cellulitis since the initiation of the Haemophilus influenzae B vaccine, and is contraindicated in those with a history of ulcerative or pseudomembranous colitis.

If clindamycin is contraindicated, the next line of therapy should be either trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, contraindicated in those with sulfa allergies, or doxycycline, which should be avoided in children under the age of eight.1-7 Pregnant or nursing mothers should avoid trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as well as doxycycline, and clindamycin is thought to be safe only in the second or third trimester of pregnancy.1-8 Previously, it was recommended to use amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefpodoxime or cefdinir as first line, but this is no longer used as these medications have poor coverage over MRSA and anaerobes.1-7

For those who are immunocompromised and cannot take clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline is recommended in combination with amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefpodoximine or cefdinir. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline carry poor coverage against group A Streptococcus whereas amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefpodoxime and cefdinir have poor coverage against MRSA and anaerobes.4-8 The dosages for each of the above medications is listed in Table 1.

Rarely are IV antibiotics needed except for patients with preseptal cellulitis at a higher risk for developing orbital cellulitis. This is the case for infants less than one year old, immunocompromised patients or patients without immunization against Haemophilus influenzae and Strep. pneumonia.2,3 Intravenous therapy options include piperacillin/tazobactam, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefuroxime and ceftriaxone. Vancomycin should be added if MRSA infection is suspected.

For patients allergic to penicillins or cephalosporins, it is recommended to add ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin to vanomycin.9 These patients should be referred promptly to the emergency room or oculoplastic specialist for evaluation and initiation of therapy.

However, regardless of immune status, all patients with preseptal cellulitis should be monitored closely due to the low but possible risk of progression to orbital cellulitis. If symptoms worsen within 24 to 48 hours, prompt referral to the emergency room should be initiated unless access to an oculoplastic specialist is readily available.2,3

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Orbital Cellulitis

While both preseptal and orbital (postseptal) cellulitis arise from infection, orbital cellulitis has increased risk for infraorbital abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis, encephalomeningitis, sepsis and intracranial abscess.1,2 Orbital cellulitis occurs when an infectious or inflammatory process is present behind the orbital septum. The source may be local or distant. The paranasal sinuses are the most common source of infection for both adults and children when post-septal infection occurs.2

There are several areas of anatomical weakness within the orbit that can predispose an individual to orbital cellulitis.2 Within the subperiosteal space, the periorbita has some loose attachments to the bony orbit in areas outside the orbital suture lines. The orbital veins, which allow venous drainage of the paranasal sinuses, cavernous sinus and pterygoid plexus, can also predispose this area to infection, as they do not contain valves.2 These various disadvantages around the eye can allow superficial sinus infections within the face to gain access to the cavernous sinus and pterygoid plexus. Within the paranasal sinuses, there are additional structural challenges that can also result in easier passage for an infectious process.

Due to the thinness of the medial wall separating the orbit from the ethmoid sinus, it is the most common location for subperiosteal abscesses. The next common location for subperiosteal abscesses is from the maxillary sinus through the thin inferior orbital floor wall.2 While the superior orbital roof is thicker than the inferior or medial walls of the orbit, severe frontal sinus infections can lead to severe complications, including epidural abscess, subdural abscess, intracerebral abscess and meningitis if the infection pierces through the superior roof.2 Finally, posteriorly in the orbital space, the sphenoid sinus sits next to the orbital apex and optic nerve and, as such, infections in this confined, post-septal space can result in severe visual complications.2

|

|

Extensive eyelid edema suggestive of preseptal vs. orbital cellulitis warranting further clinical evaluation. Click image to enlarge. |

In addition to infections spreading from various sinuses surrounding the ocular tissue to areas behind the septum, the spread of infection from the upper respiratory tract to the orbit is also a major cause of orbital cellulitis.2,3,9 This, along with a relatively larger size of ethmoid sinus, is the reason that orbital cellulitis is more common in children compared with adults.2,9

Other causes of orbital cellulitis include dacryocystitis, endophthalmitis, panophthalmitis, untreated preseptal cellulitis, dental infections generally spread through the maxillary sinus and hematogenous spread in the setting of bacteremia from distant sources.3,10,11 Trauma or surgery is a common source of orbital cellulitis in developing countries but is rare in developed countries.3

Patients with orbital cellulitis are more likely to present with a recent history of sinus or upper respiratory infection to include fever, fatigue, headache or nasal congestion. Additional ocular symptoms may include vision loss, afferent pupillary defect, diplopia, pain with eye movement, exophthalmos and orbital pain. These symptoms are experienced if the inflammation and infection press upon or restrict various structures around the orbit, such as the cranial nerves, extraocular muscles.1-9 However, there will be times when the clinical difference between the two conditions is unclear. In these instances, or for individuals with high suspicion of orbital cellulitis or a suspicion of a retained intraorbital or intraocular foreign body, it is recommended to obtain computerized tomography with contrast or magnetic resonance imaging n cases where no metallic foreign body is suspected.

Imaging of preseptal cellulitis will show eyelid swelling, no proptosis, no fat stranding of orbital contents and no involvement of the extraocular muscles, whereas orbital cellulitis will demonstrate orbital involvement.8,9 Imaging can also be beneficial to demonstrating where a foreign body entered the orbit as well as localizing abscesses in cases of orbital cellulitis.8,9

Differential diagnosis. The list of conditions that can mimic orbital cellulitis is both extensive and diverse, encompassing a wide range of primary and secondary disorders. Among the primary neoplasms that may present with symptoms like orbital cellulitis are rhabdomyosarcoma, most often occurring in children under the age of seven, a malignant tumor of the soft tissues often found in the orbit, and retinoblastoma, a rare but serious cancer that primarily affects the retina but can spread to the orbital area.3,5,7,10,11 In addition to these primary tumors, metastatic neoplasms can also present with symptoms resembling orbital cellulitis. These include secondary tumors that have spread to the orbit from other primary sites, as well as hematologic malignancies such as leukemia and lymphoma, which can present orbital involvement and swelling.

Furthermore, certain rheumatologic conditions can mimic orbital cellulitis, such as complications of sarcoidosis, orbital pseudotumor, thyroid orbitopathy, and Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Each of these diagnoses would be distinguished through imaging modalities and history.3,5,7,10-11

An example of a rheumatologic associated condition that may mimic components of orbital cellulitis that would not be detected by standard imaging modalities is temporal arteritis or giant cell arteritis, an inflammation of the medium to large arteries, including those supplying the head and eyes, that may present with orbital pain and swelling. The potential for other conditions based on presentation, other findings or history may require different diagnostic and therapeutic approaches compared to orbital cellulitis, underscoring the importance of a thorough evaluation to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.3, 7-9

It is important to note that pre-pubescent children are at higher risk of orbital cellulitis, with an incidence of 1.6 per 100,000 in the pediatric population vs. 0.1 per 100,000 in adults. Children are not only more likely but also more susceptible to the serious secondary complications of orbital cellulitis, such as optic neuropathy, orbital abscess, meningoencephalitis and brain abscess, because of their immature immune system.2-4

|

|

Unilateral edema of upper eyelid and lower eyelid that extends into the orbit, concerning for orbital cellulitis. Click image to enlarge. |

Prognosis and management. The prognosis of orbital cellulitis when treated early with antibiotics is good. In the pre-antibiotics era, the mortality rate from associated conditions such as cavernous sinus thrombosis and intracranial abscess was 19%. The rate of vision loss was 20%.9 With the appropriate diagnosis and early intervention with antibiotics, the overall rate of vision loss for orbital cellulitis currently approaches zero, with reports of up to 11% of patients experiencing some vision loss. In cases where orbital cellulitis progresses to endophthalmitis, there is a higher risk for poor visual outcomes.11

The mortality rate associated with orbital cellulitis approximates 1% to 2%, but it may be as high as 40% in patients with intracranial abscess.11 Unfortunately, patients with orbital cellulitis in low- and middle-income countries tend to seek care later in the course of the disease and hence are more likely to experience complications. It is possible that even in developed countries, patients with low socioeconomic status, lack of health insurance and poor access to health care may also delay care.1-3,10,11

Due to the potential for sight- and life-threatening complications, orbital cellulitis should be referred to a physician for urgent imaging and hospitalization whenever possible. Typically, an oculoplastics specialist is best suited to care for these patients; however, an emergency room referral is also appropriate. Patients should be promptly started on empiric intravenous antibiotics, usually targeting gram-positive organisms, while awaiting results of a culture and sensitivity analysis. The most common inciting organisms are Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.9

If needed, antibiotic therapy can be modified once these results are reviewed. IV vanocomycin is generally recommended in those with normal renal function, in addition to either ceftaxomine, piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftriaxone or ampicillin-sulbactam.9 Also, the underlying condition—often sinusitis—must be managed with nasal decongestants, saline irrigation or intranasal corticosteroids. For those with concerns for systemic infection, blood cultures are recommended, and those with concerns of meningitis should receive a lumbar puncture.2,4,9

In immunocompromised individuals, a biopsy should be considered to investigate potential fungal etiologies. In patients with poorly controlled diabetes, the concern for fungal mucormycosis, caused by Mucorales, arises when patients present with orbital apex syndrome, which involves multiple extraocular muscles and the optic nerve.2,4 Other fungal organisms known to cause orbital cellulitis include Aspergillus, most commonly found in those with immune deficiencies, and rarely Mycobacterium tuberculosis.2,4,5,9,12 Those with confirmed fungal cases should receive intravenous antifungal therapy with medications such as amphotericin B or voriconazole, and typically require surgical debridement.2,4,5,12

|

|

A patient with chronic styes presents with an associated preseptal cellulitis. Click image to enlarge. |

The addition of intravenous corticosteroids for those with orbital cellulitis of various etiologies is controversial, as steroids may help to reduce the inflammatory process and protect the ocular structures at the cost of potentially suppressing the immune system response.2

Surgery is indicated for those with a history of foreign body, those who worsen or do not respond to medical management, those whose visual function deteriorates, or for those with orbital abscesses. The timing of surgical drainage in those with abscesses varies amongst surgeons, with some surgeons recommending immediate drainage and others electing to wait and see if the patient responds to medical management first. Those with orbital abscesses usually require surgical drainage, whereas subperiosteal abscesses tend to resolve on medical management and not require drainage.2

Takeaways

The clinical distinction between preseptal and orbital cellulitis is imperative for a clinician to make due to the potential visual and systemic complications with the latter. While preseptal cases are generally mild and resolve with oral antibiotics, particular care must be taken for infants, children and immunocompromised individuals.

Orbital cellulitis can not only be sight-threatening but can also be life threatening. Thus, prompt treatment for both conditions is important, as is close monitoring, to ensure the patient is responding as expected based on the diagnosis made and there is no evidence of progression.

The eyecare physician should do a thorough exam to include inquiring about symptoms of recent trauma, illnesses and ocular pain as well as visual acuity testing, pupil assessment, extraocular muscle assessment and a thorough anterior and posterior segment evaluation. Potential additional in-office assessments include exophthalmometry, assessment for fever and assessments to rule out an ocular foreign body. If there is any suspicion of orbital cellulitis or any concern for immunocompromised status, the patient should be urgently referred to an appropriate physician for imaging, cultures and treatment.

Dr. DeWilde works as a TeleEye optometrist at the VA for the VISN 22 Clinical Resource Hub in addition to lecturing at state, national and international meetings.

Dr. Toms is currently a staff optometrist for Virtual Eyecare Providers within the VA through VISN 23 Central Resource Hub. Prior to their roles within tele-eyecare, both Dr. Dewilde and Dr. Toms worked at the Kansas City VAMC and served as adjunct faculty for University of Missouri-St Louis College of Optometry. They have no financial or advisory conflicts of interest.

1. Gordon AA, Phelps PO. Management of preseptal and orbital cellulitis for the primary care physician. Dis Mon. 2020;66(10):101044. 2. Lee S, Yen MT. Management of preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2011;25(1):21-9. 3. Tsirouki T, Dastiridou AI, Ibánez Flores N, et al. Major review: orbital cellulitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63(4):534-53. 4. Wong SJ, Levi J. Management of pediatric orbital cellulitis: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;110:123-9. 5. Danishyar A, Sergent SR. Orbital cellulitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507901/. Last updated August 8, 2023. Accessed October 16, 2024. 6. Jones D B, Steinkuller P G. Strategies for the initial management of acute preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1988;86:94-108 7. Monsivais-Rodríguez, FV, Yen MT, Tsui JC, Burkat CN. Preseptal cellulitis. EyeWiki. eyewiki.aao.org/preseptal_cellulitis. April 18, 2024. Accessed September 10, 2024. 8. Murphy PB, Bistas KG, Patel P, et al. Clindamycin. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519574/. Updated February 28, 2024. Accessed October 16, 2024. 9. Mejia E, Vohra V, Braiman M. Ocular cellulitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513319/. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed October 16, 2024. 10. Bourget D, Bae C. Periorbital cellulitis. StatPearls. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470408/. Last updated July 17, 2023. Accessed September 10, 2024. 11. Pelletier J, Koyfman A, Long B. High risk and low prevalence diseases: orbital cellulitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;68:1-9. 12. Farooq AV, Patel RM, Lin AY, et al. Fungal orbital cellulitis: presenting features, management and outcomes at a referral center. Orbit. 2015;34(3):152-9. |