|

|

It’s important to communicate with the patient’s comanaging doctors to adjust necessary medications. There are four direct oral anticoagulants approved for atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran (Pradaxa), edoxaban (Savaysa) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Click image to enlarge. |

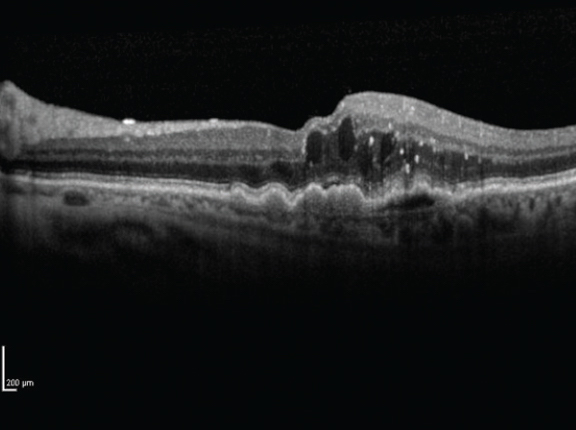

The body is an interconnected system and, as clinicians know, side effects from one treatment may wreak havoc in other areas of the body. A recent study published in Ophthalmology highlighted the delicate balancing act of medication management for the prevention of life-threatening cardiac events and sight-threatening diseases when it reported that warfarin significantly increased the risk of conversion to neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

A newer class of blood thinners called direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have proven superior in several studies compared with traditional warfarin and are preferred first-line agents for stroke prevention in certain cases. However, all anticoagulants are associated with bleeding risks, and DOACs’ intraocular complications aren’t clear yet. Researchers sought to understand the risks in patients with higher bleeding risk such as those with AMD.

The study included patients with non-neovascular AMD initiated on DOACs (n=20,300) or warfarin (n=13,387). Researchers found that at six months and at one year, patients treated with warfarin had a higher risk of developing neovascular AMD compared with those who were treated with DOACs. They also reported that warfarin-treated patients had an increased risk of requiring intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy and pars plana vitrectomy.

Additionally, patients with AMD and atrial fibrillation had an increased risk of ocular complications and need for anti-VEGF therapy over a five-year period. The researchers reported no significant difference in the development of major systemic hemorrhagic events in the two groups over five years.

Based on the real-world study findings, the researchers wrote that patients with non-neovascular AMD on warfarin are at an increased risk for developing ocular complications such as neovascular disease, macular hemorrhage and vitreous hemorrhage, and are more likely to require anti-VEGF therapy or surgical vitrectomy than patients on DOACs.

“Furthermore, there was an observed increased risk of these same events when evaluated over an extended continuous five-year period in a cohort of individuals with dry AMD receiving the anticoagulation for the indication of chronic atrial fibrillation,” the researchers added in their Ophthalmology paper.

They concluded that “switching oral anticoagulation from warfarin to select FDA approved DOACs in patients with subsequent neovascular AMD and/or history of neovascular AMD must be considered carefully, given the improved bleeding profile highlighted in the present study.”

Alsoudi AF, Koo E, Wai K, et al. Risk of ocular neovascular conversion and systemic bleeding complications in patients with AMD on DOACs or warfarin. Ophthalmology 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. |