|

|

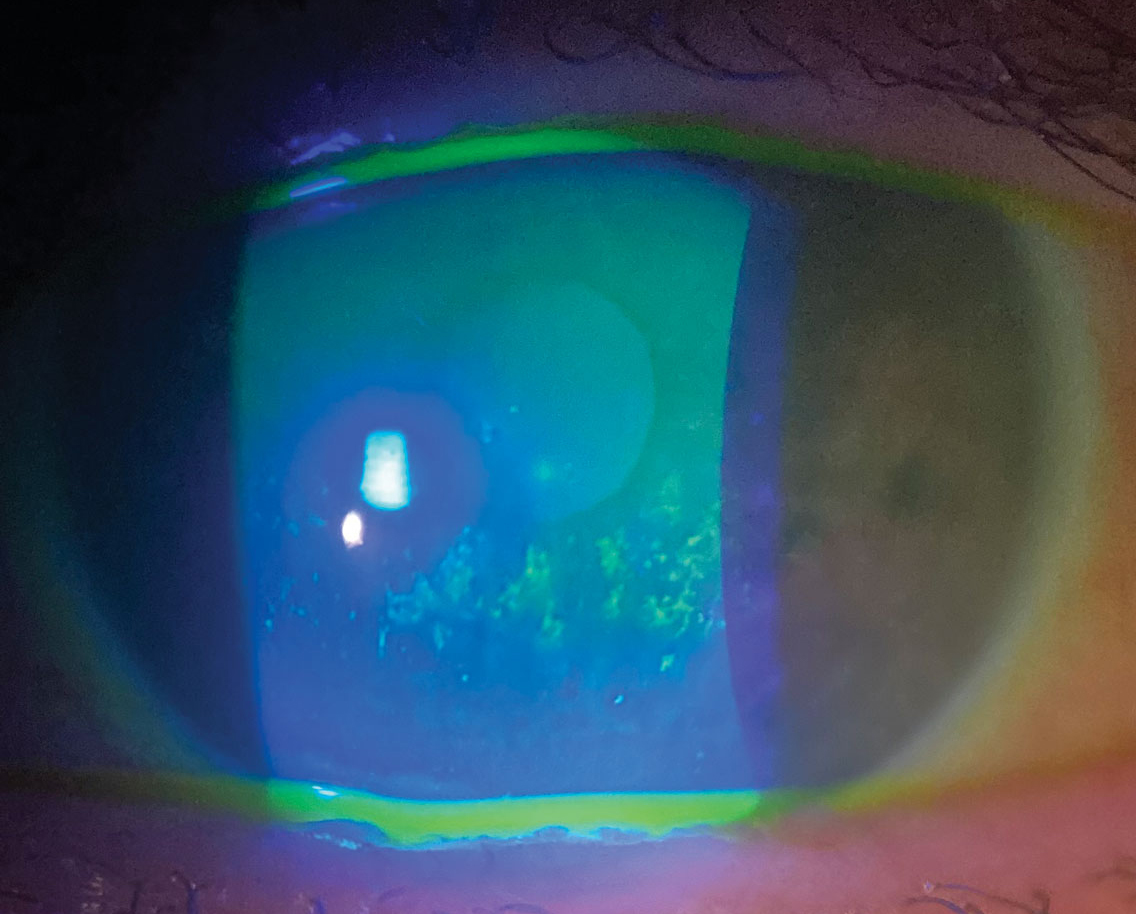

Current literature seems to disagree on the actual number of patients who suffer from DED or MGD. Photo: Pam Theriot, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

While dry eye may seem ubiquitous in eyecare practices, surprisingly little is known about its actual prevalence in the general population. A study recently published in JAMA Ophthalmology sought to close this gap, examining the prevalence and incidence of dry eye in relation to meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD).

Since MGD is the hallmark cause of evaporative dry eye, the researchers retrospectively examined 13 studies for data on dry eye and MGD. Analysis indicated that pooled dry eye prevalence in the US population was 8.1%—with estimates in individual studies ranging anywhere from 5.3% to 14.5%—while pooled MGD prevalence was 21.2% but ranged from 10.4% to 55.4%. Annual incidence of dry eye was 3.5% in the population age 18 or older, increasing to 7.8% per year among the 68 or older population. None of the studies reported MGD incidence.

The authors note that the wide range seen in prevalence estimates for dry eye reflects the heterogeneity of clinical and methodological approaches in these studies. Factors that added to uncertainty of a prevalence estimate included variations of study design and setting, varied population characteristics and no standard definition used for dry eye. For instance, one study defined dry eye with relevant diagnostic codes, while another defined it by self-reported diagnosis or symptoms. Part of this high range in prevalence percentage may be in part due to population age differences.

The pooled prevalence may additionally be inflated by studies that are either subject to being unrepresentative of the actual population or at high risk of bias. One example would be a study using data gathered from the Veterans Affairs healthcare system. While this data may be representative of the veteran population, the predominance of males and the unique exposures that veterans may experience makes the 26.2% prevalence estimate for dry eye an estimation specific only to the population of the study conducted, rather than the general population.

Several diagnostic criteria, spanning numerous studies, were included in the dry eye prevalence estimation. However, because these multiple criteria were not replicated across other studies, uncertainty within the prevalence of the underlying population was compounded. With MGD, the range seen in prevalence estimates may be result of differences in clinical signs used to diagnose the condition.

As the authors point out that other conditions (e.g., glaucoma, AMD) have already received standard diagnostic classifications by expert consensus, they argue that dry eye too deserves “a set of working diagnostic criteria for DED is necessary to allow standardization and comparisons in dry eye epidemiological studies,” they wrote in their paper. While this research starts to fill the knowledge gap in a prominent area of eye care, the authors, recognizing the issues with the data, urge clinicians to remember that “the evidence provides uncertain estimates of dry eye burden and highlights the need for further studies that minimize risk of bias and use validated diagnostic criteria.

McCann P, Abraham A, Mukhopadhyay A, et al. Prevalence and incidence of dry eye and meibomian gland dysfunction in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. October 27, 2022. [Epub ahead of print]. |