|

|

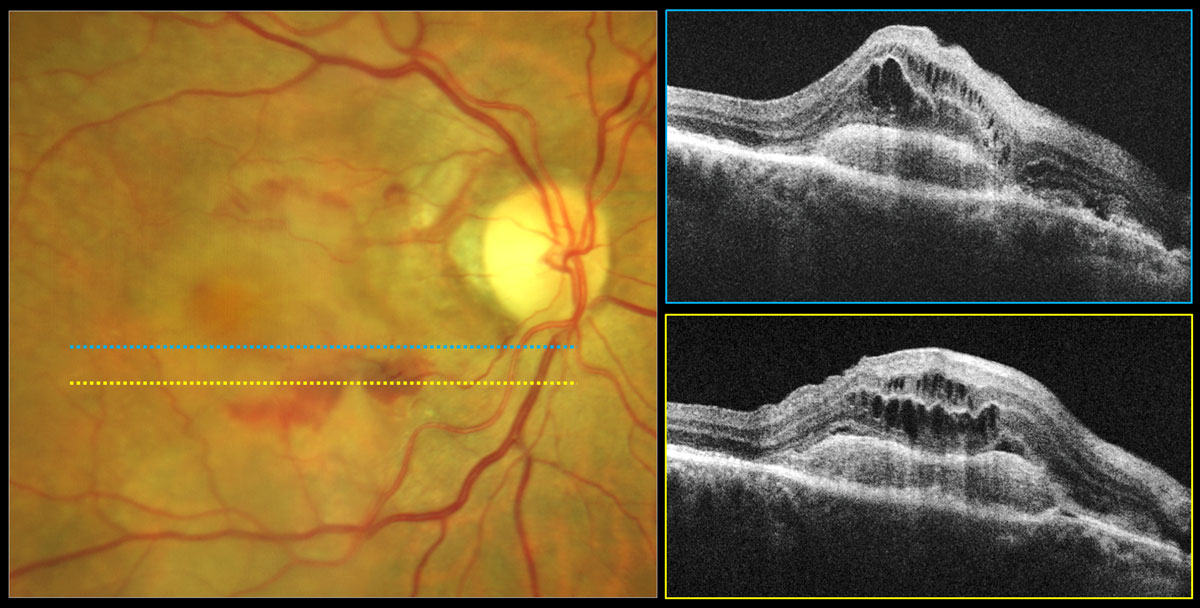

Age-related eye diseases like AMD were not associated with notably higher rates of dementia, depression or anxiety in this study. Photo: Carolyn Majcher, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania wanted to examine manifestations of visual impairment in dementia and related conditions. “Because half of all vision loss in the US is preventable or treatable, these findings raise the question of whether efforts to reduce visual impairment could prevent neuropsychiatric impairment in older adults at the population level,” they wrote in a recent paper for Ophthalmic Epidemiology. Self-reported visual difficulty has already been linked with dementia and other neuropsychiatric outcomes, but existing studies on age-related eye diseases have resulted in conflicting findings.

This group of researchers retrospectively examined data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Totaling 10,089 participants, the dataset is an ongoing, nationally representative survey of older adults in the US. The researchers then used Medicare claims data to identify those with age-related macular degeneration, primary open angle glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy (DR) and cataract. Researchers selected controls for each condition with complete Medicare eligibility and at least one eyecare encounter.

After analyzing data on these patients, the authors were able to determine that self-reported visual difficulty was associated with dementia, depression, anxiety and hallucinations. DR was also associated with depression, while cataract interestingly displayed a lower depression and anxiety risk. No other associations were seen between age-related eye disease and neuropsychiatric outcomes. As such, it can be generalized that self-reported visual difficulty is associated with dementia and other neuropsychiatric outcomes to a greater degree than age-related eye diseases are with such conditions.

The association between self-reported visual difficulty and dementia, depression, anxiety and hallucinations are consistent with previous reports and other patient populations. Many mechanisms might be the cause of this relationship, such as a direct effect of functional deafferentiation in brain function, vision-related changes in physical activity or social engagement. However, hallucinations are especially useful in understanding a potential directly causal relationship between visual and cognitive function. Visual hallucination pathogenesis is directly linked to the visual cortex, and vision loss from anterior visual pathway disease can independently produce hallucinations in the absence of a comorbid neurological or psychiatric disorder. The authors add, though, that age-related eye disease would be associated with these outcomes if visual impairment was a significant cause of neuropsychiatric impairment at the population level.

The investigators also point out an inconsistency between ophthalmic disease and neuropsychiatric outcomes, whereas self-reported visual difficulty display robust associations with all outcomes examined. One possibility for this is the potential contribution of other conditions like uncorrected refractive error. As the authors explain, diagnosis alone may not be an adequate indicator of visual function, even if all major visual impairment causes were captured, because many eye diseases display minimal or no vision loss in early or mild stages.

Finally, the inverse association of cataract with depression and anxiety risk may be an artifact that arises due to greater healthcare use among such individuals. “Patients who see an ophthalmologist or optometrist for monitoring of cataracts may have fewer comorbidities or be more likely to participate in health maintenance compared to patients who see eyecare providers for different reasons,” they wrote in their paper.

The authors believe that, since age-related eye disease was not consistently associated with neuropsychiatric outcomes like self-reported visual difficulty was, it “raises questions about whether associations for self-reported visual difficulty are reflective of visual function and, thus, whether enhanced screening or treatment of eye disease in the older adult population would reduce the risk of these outcomes, though further research is needed to answer these questions.”

Hamedani AG, Willis AW, Ying GS. Self-reported visual difficulty, age-related eye disease, and neuropsychiatric outcomes in older adults. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. May 8, 2024. 1-9. |