|

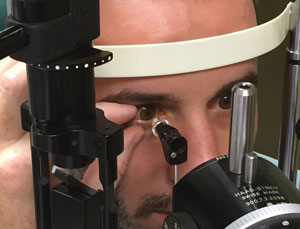

| Although POAG screening has been shown to be accurate and effective, performing these tests on every patient may lead to overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment. Photo: Natalie A. Townsend, OD, and John J. McSoley, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The burden on primary care clinicians to triage nearly every condition imaginable is profound, and these busy doctors need to know what their part looks like in identifying patients with glaucoma and referring them for further evaluation. However, their role remains unspecified. In updating its 2013 recommendation, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently concluded that there is still not enough evidence to assess whether the benefits outweigh the harms of screening for glaucoma in GP offices. This finding applied to adults 40 and older who did not have signs or symptoms of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).1 While the task force found adequate evidence that screening tests can identify POAG, these screening tests were not commonly found in primary care settings.2

The USPSTF commissioned a systematic review of 53 studies (n=65,464) to evaluate the benefits vs. harms of screening for POAG in adults.

Despite advances in the diagnostic tests that ophthalmologists can perform, no combination of assessments can diagnose glaucoma in asymptomatic adults with sufficient sensitivity and specificity to be useful, particularly outside of an eye clinic setting, an editorial in JAMA noted.3

Although the USPSTF found adequate evidence that treatment of glaucoma reduces intermediate outcomes such as intraocular pressure (IOP), visual field loss and optic nerve changes, there was not enough evidence to conclude that these changes would improve health outcomes such as visual impairment, vision-related function and quality of life.2 Because there was not an obvious link, it was unclear if changes in intermediate outcomes can translate into tangible health outcomes for patients.2

People with POAG may not have increased IOP, and increased IOP may not result in nerve damage or visual impairment. Many patients with glaucoma do not have symptoms. However, once vision loss occurs—usually slow loss of side vision or peripheral vision—the optic nerve is already damaged.2

Because not all people who are diagnosed with and treated for open-angle glaucoma progress to visual impairment, a possible harm of screening tests includes unnecessary treatment. Possible harms caused by treatment of glaucoma include formation of cataracts resulting from surgery, topical medications or both.1

Moving Forward

The USPSTF clarified that its statement is a recommendation neither for nor against screening. The task force has called for more studies that target the following areas:2

Trials that include larger numbers of Black and Hispanic/Latino patients reporting on the effects of screening and treatment of POAG.

Cases of referral to an eyecare specialist and use of contemporary screening and diagnostic modalities (e.g., spectral-domain OCT or swept-source OCT) that are of sufficient duration and include vision-related outcomes (visual impairment, vision-related function, quality of life and other patient-reported outcomes).

Accuracy of risk assessment tools both for early identification of people at increased risk of glaucoma and to inform screening strategies.

Long-term effects of treatment on visual impairment, vision-related function and quality of life to verify that benefits of treatment are retained in patients diagnosed with POAG using newer imaging methods such as OCT.

In the meantime, a JAMA Ophthalmology editorial by prominent glaucoma specialist Harry Quigley, MD, suggested the internist/family physician three questions as risk assessments that could point to the need for an ophthalmic examination:4

Have you had a detailed eye examination beyond simply having your glasses measured?

Do you have a blood relative who had glaucoma or blindness?

Were you told in the past you have glaucoma but stopped going for treatment?

The editorial in JAMA noted that the day may come when images of the optic nerve and retina are routinely obtained in a primary care office or other settings and when such images can be accurately categorized by an artificial intelligence algorithm as normal or demonstrating disease.3

“Until that time, and until additional evidence on screening for glaucoma is available, primary care clinicians should not necessarily conclude that there is no utility in screening for glaucoma but rather may attempt to determine which patients are at highest risk through history-taking and direct them to an eyecare specialist,” the study authors wrote.3

1. Jin J. Screening for primary open-angle glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;327(20):2030. 2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for primary open-angle glaucoma: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;327(20):1992-7. 3. Jampel HD, Shukla AG. Screening for glaucoma. JAMA. 2022;327(20):1961-2. 4. Quigley HA. Identifying glaucoma in primary care offices. JAMA Ophthalmol. May 24, 2022. [Epub ahead of print]. |