|

Dry eye can be caused or exacerbated by many things, not the least of which is dehydration. Indeed, we have long been aware of the multifactorial nature of dry eye disease (DED), yet we have paid comparatively less attention to specifically how and why whole body hydration is an important consideration in dry eye etiology and management, something that is backed by research and can be a meaningful therapeutic strategy.1-3

Here, we will review the scientific literature on the effects and measurement of hydration and recommend practical strategies that can help patients improve whole-body hydration in a manner that is specifically designed to optimize ocular surface health.

Ocular Structures and Systems

The effects of whole body hydration on the eyes are staggering, although not surprising since water is a major constituent of the eye.4 In fact, the tear film, aqueous and vitreous are over 98% water.5 A systematic review shows that hydration affects the ocular physiology, morphology, ocular pathophysiologic processes and disease states found in both the front and back of the eye, including dry eye, cataracts, refractive changes, glaucoma and retinal vascular disease.3

|

|

Minimal tear meniscus height, pictured here, is indicative of aqueous-deficient dry eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Hydration Challenges

Despite apparent challenges associated with patients’ ability or willingness to improve whole-body hydration, optometrists should do their part to at least convey the relevance of hydration on ocular well-being. Ideally, our conversations should extend beyond cliché reminders to drink more water and include specific directions on how to meet eye health hydration standards.

Biometric Measurement Alternations That Respond to Hydration Status:3

|

Hydration isn’t as simple as drinking lots of water. Electrolytes also play an important role in reaching and maintaining healthy hydration levels—so much so that in the Women’s Health Study, which included over 50,000 participants, researchers concluded that recommending increased water intake is not justifiable, as water by itself has not been proven to decrease the risk of DED.14

Recognizing that drinking a lot of water can be a burden, many patients have turned to sports drinks and other high-electrolyte beverages. While these can help overcome dehydration quicker, many are unsuitable for regular use due to high sugar content. Also, none of these beverages are specifically formulated with ingredients shown to benefit ocular structures in particular.

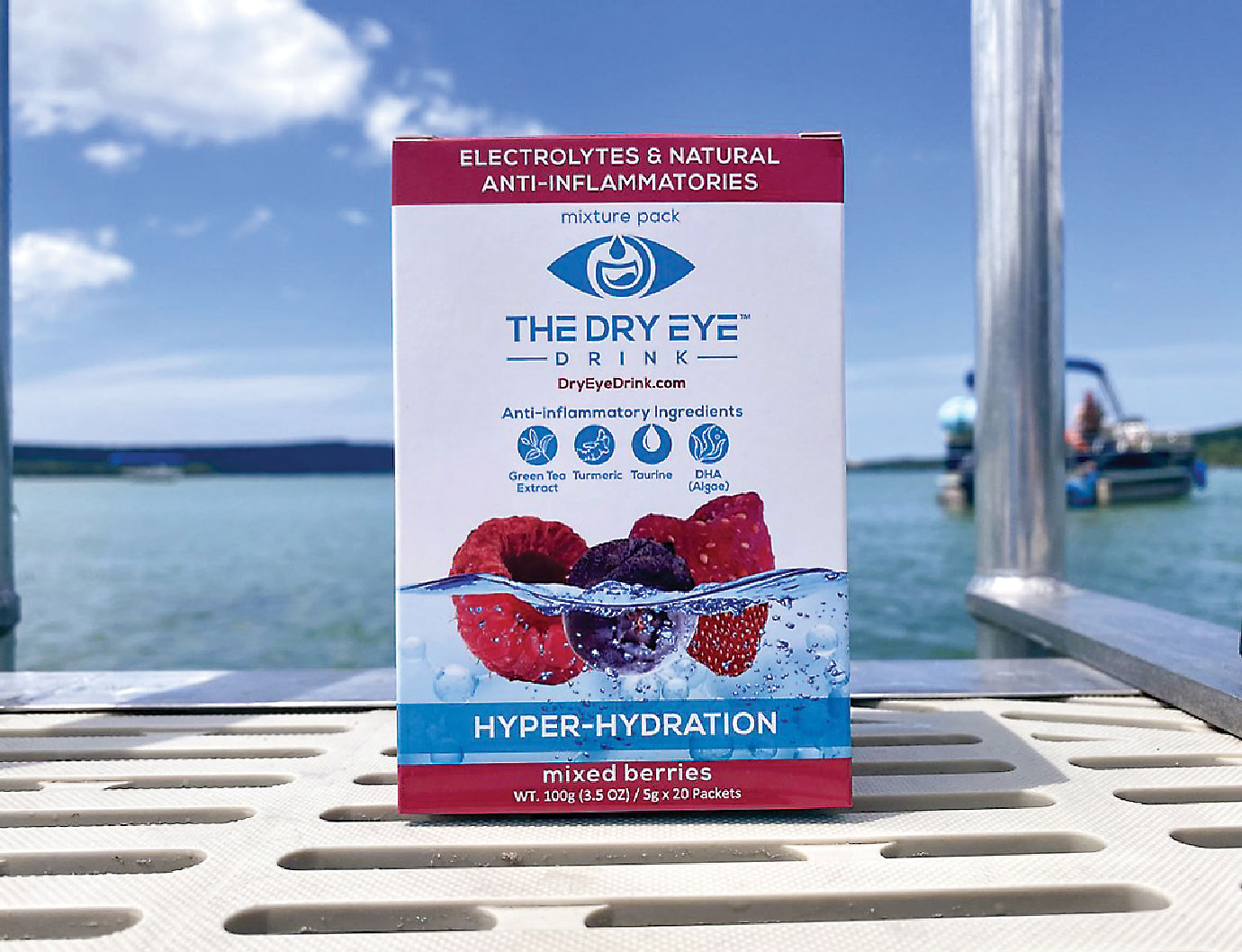

Dry Eye Drink

Recognizing the need for something eyecare providers could confidently recommend to a broad base of patients—many of whom enjoy flavored beverages, yet may not be likely to adhere to drinking large quantities of water—a new product was developed, known as the Dry Eye Drink. This specifically formulated powdered drink pack is meant to be added to water and consumed twice per day to help hyperhydrate patients without the deleterious effects of sugar.

After testing 43 formulations, the final version was developed with other vitamins that have been shown to benefit the ocular surface, such as vitamins A, B3, B6, B12 and C. The Drink Eye Drink also includes turmeric, DHA, taurine and green tea, as well as natural electrolytes and omega-3s, which help decrease inflammation.

Hydration Terms3

|

The product has shown clinical benefits and new versions were recently developed. Patient feedback indicated that for caffeine-sensitive individuals, the original daytime formula can cause restlessness when taken immediately before bed, which led to a “PM” version that replaced the B vitamins and green tea extract with melatonin, chamomile extract and Valerian root extract. In other words, it was designed to not only aid dry eye, but also sleep issues. Lack of adequate sleep has been associated with DED, and DED has been shown to affect sleep quality.15,16 Anecdotally, one of the primary causes of treatment-resistant DED is inadequate lid seal, which may also play a key role in poor sleep quality.

As we learn more about the role hydration plays in dry eye, whole body hydration—specifically the Dry Eye Drink—may help more patients in their journey to better ocular surface health.

|

|

Dry Eye Drink is a combination of turmeric, DHA, taurine, green tea and natural electrolytes, which helps decrease inflammation. Click image to enlarge. |

Special thanks to Josh Davidson, OD, for his contributions to this column.

Dr. Karpecki is the director of Cornea and External Disease for Kentucky Eye Institute, associate professor at KYCO and medical director for Dry Eye Institutes of Kentucky and Indiana. He is the Chief Clinical Editor for Review of Optometry and chairman of the affiliated New Technologies & Treatments conferences. A fixture in optometric clinical education, he provides consulting services to a wide array of ophthalmic clients. Dr. Karpecki’s full disclosure list can be found here.

1. Lemp MA. Advances in understanding and managing dry eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(3):350-6. 2. Walsh NP, Fortes MB, Raymond-Barker P, et al. Is whole-body hydration an important consideration in dry eye? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(10):6622-7. 3. Sherwin JC, Kokavec J, Thornton SN. Hydration, fluid regulation and the eye: in health and disease. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;43(8):749-64. 4. Fischbarg J. Water channels and their roles in some ocular tissues. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33(5-6):638-41. 5. Bishop PN. Molecular composition of the vitreous and aging changes. Encyclopedia of the Eye. 2010:37-43. 6. Fortes MB, Diment BC, Di Felice U, et al. Tear fluid osmolarity as a potential marker of hydration status. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1590-7. 7. Sabetti L, Renzetti A, D’Alessandri L, Balestrazzi E. Eventual error caused by dehydration with pachometry. Ophthalmologica. 2001;215(2):97-101. 8. Hunt A, Feigl B, Stewart I. The intraocular pressure response to dehydration: a pilot study. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(5):1963-6. 9. Read SA, Collins MJ. Water drinking influences eye length and IOP in young healthy subjects. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91(2):180-5. 10. Susanna R Jr, Vessani RM, Sakata L, et al. The relation between intraocular pressure peak in the water drinking test and visual field progression in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(10):1298-301. 11. Nowroozzadeh MH, Mirhosseini A, Meshkibaf MH, Roshannejad J. Effect of Ramadan fasting in tropical summer months on ocular refractive and biometric characteristics. Clin Exp Optom. 2012;95(2):173-6. 12. Inan UU, Yucel A, Ermis SS, Ozturk F. The effect of dehydration and fasting on ocular blood flow. J Glaucoma. 2002;11(5):411-5. 13. Balk LJ, Sonder JM, Strijbis EM et al. The physiological variation of the retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and macular volume in humans as assessed by spectral domain-optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(3):1251-7. 14. Nguyen L, Magno MS, Utheim TP, et al. The relationship between habitual water intake and dry eye disease. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2023;101(1):65-73. 15. Li A, Zhang X, Guo Y, et al. The association between dry eye and sleep disorders: the evidence and possible mechanisms. Nat Sci Sleep. 2022;14:2203-12. 16. Magno MS, Utheim TP, Snieder H, et al. The relationship between dry eye and sleep quality. Ocul Surf. 2021;20:13-9. |