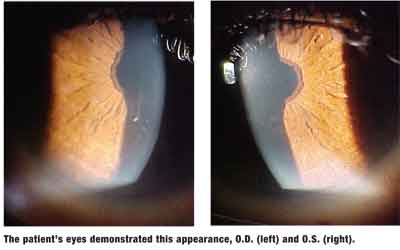

A 69-year-old black female presented complaining of haloes and glare in both eyes, at distance and near, occurring for the past two weeks. Her systemic history was significant for hyperthyroidism, hypercholesterolemia, atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure. For these, she was medicated with Zestril (lisonopril, AstraZeneca), Norvasc (amlodipine, Pfizer), Coumadin (warfarin, Bristol-Myers Squibb), Synthroid (levothyroxine, Abbott) and amiodarone.

She said she occasionally wore silicone hydrogel contact lenses. She denied ocular injuries or surgeries and reported no known allergies.

Diagnostic Data

Her best-corrected entering visual acuity was 20/30 O.U. at distance and near. External examination was unremarkable. Pupils were equal and reactive to light with no afferent defect, and confrontation visual fields using facial Amsler grid were normal.

Your Diagnosis

How would you approach this case? Does this patient require additional tests? What is your diagnosis? How would you manage this patient? What is the likely prognosis?

Discussion

Additional testing included dilated fundus examination, Humphrey automated SITA-standard 24-2 visual field testing, color vision testing with Ishihara plates, brightness comparison testing, photo stress testing and photodocumentation.

The diagnosis in this case is amiodarone corneal verticillata, producing corneal epithelial eruption and abscess secondary to a sudden large increase in dosage. Upon further history, the patient explained that she began seeing a new cardiologist six weeks earlier; that doctor tripled her daily dosage of amiodarone from 100mg to 300mg.

Amiodarone is a potassium channel-blocking antiarrythmic medication indicated for recurrent ventricular fibrillation and recurrent hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia. In recent years, it has become the most frequently prescribed antiarrhythmic agent in the United States.1-7

Following oral administration, amiodarone is slowly and variably absorbed and metabolized in the liver to N-desethylamiodarone (N-DEA). Both amiodarone and its primary metabolite, N-DEA, are highly protein and lipid bound, and there is extensive accumulation in various sites, especially adipose tissue and highly perfused organs, such as the liver, lung and spleen.2,7

Amiodarone has documented side effects that affect many organs and systemsincluding the central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, cardiac system, pulmonary system, endocrine system and hepatic systemas well as the eyes. Ocular side effects include optic neuropathy and/or neuritis, papilledema, corneal deposits, corneal degeneration, photosensitivity, discomfort, scotoma, lens opacities, and agitation of macular degeneration processes.2,3

Ocular side effects are physiologically based on the accumulation of amiodarone and N-DEA, as well as intracellular lamellar bodies, which can induce a cytotoxic phospholipidosis.3,4,7

Fine corneal subepithelial microdeposits are the most common ocular side effect of amiodarone. These deposits are reported in 68% to 100% of patients on amiodarone therapy, with some present as soon as six to 10 days and present in virtually all eyes by three to 12 months.5 Deposition is dose dependant and reversible upon discontinuation of therapy.

Patients treated with amiodarone warrant thorough ocular examination yearly to monitor for rare but serious ocular complications. These include an optic neuropathy that resembles anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, with sudden, painless vision loss, and a pale swollen disc, often with flame-shaped hemorrhages.5-7

1. Benet LZ, Goyan JE. Bioequivalence and narrow therapeutic index drugs. Pharmacotherapy 1995 Jul-Aug;15(4):433-40.

2. Murray L, Kelly GL. Cordarone. In: Physicians Desk Reference 2002; 56:3487-3491.

3. Ingram DV. Ocular effects in long-term amiodarone therapy. Am Heart J 1983 Oct;106(4 Pt 2):902-5.

4. Kolatkar NS. Antiarrhythmic Agents. In: Pharmacology Review Notes. Houston: Iatrosoft Corporation, 1997:17-20.

5. Mantyjarvi M, Tuppurainen K, Ikaheimo K. Ocular side effects of amiodarone. Surv Ophthalmol 1998 Jan-Feb;42(4):360-6.

6. Mastropasqua L, Nubile M. Corneal Microdeposits. In: Confocal Microscopy of the Cornea. Thorofare, N.J.: Slack 2002:47-57.

7. Dovie JM, Gurwood AS. Acute onset of halos and glare: bilateral corneal epithelial edema with cystic eruptionsatypical presentation of amiodarone keratopathy. Optometry 2006 Feb;77(2):76-81.

Thanks to John M. Dovie, O.D., of Wytheville, Va., for contributing this case.