|

|

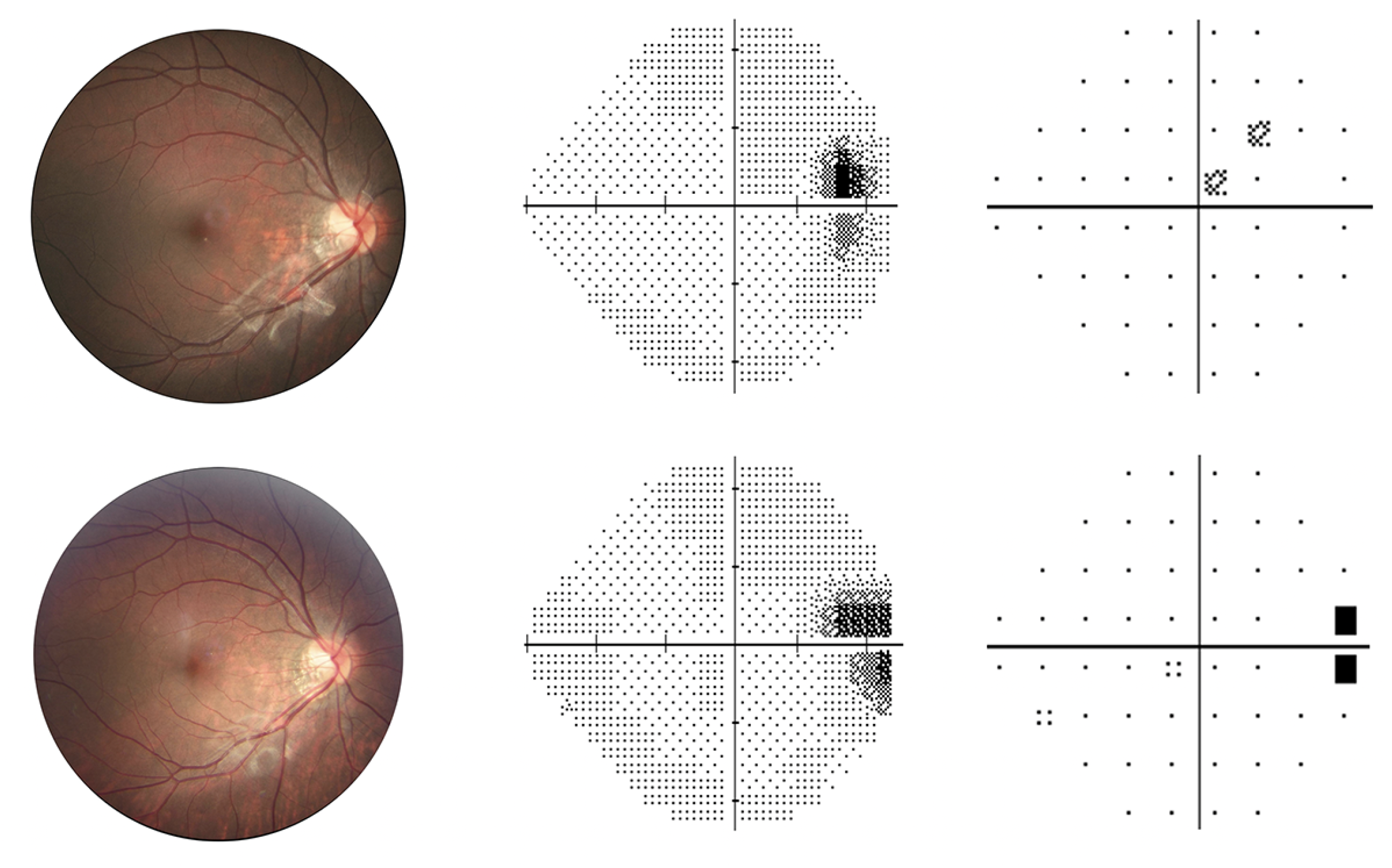

Enlarged blind spot was the most common form of visual field defect observed in this study of high myopes over an eight-year period. Photo: Li C, et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024;65(10):43. Click image to enlarge. |

Optic neuropathy associated with high myopia is one of the most frequent causes of irreversible vision loss, particularly in people of Asian ethnicity. Although this is the case, current studies that exist have been limited on this topic—especially involving highly myopic people without pathologic change. Chinese researchers aimed to bridge this gap with a new study that investigated long-term patterns and risk factors of visual field (VF) defect development in highly myopic (HM), nonpathologic patients over eight years’ observation.

Included in this study were 330 eyes from 194 patients. Of these, 49.4% of eyes developed a field defect, with 16.7% characterized as moderate or severe. The most common was an enlarged blind spot, followed by nonspecific defect, partial arcuate defect (5.5%), vertical step, nasal step (4.6%), paracentral defect (2.4%) and combined defects. At baseline, a longer axial length, thinner central corneal thickness, worse mean deviation of VF and presence of peripapillary γ-zone (defined by a whitish region presenting clearly visible sclera at the temporal optic disc margin without underlying choriocapillaris, middle-sized choroidal arteries and signs of retinal pigment epithelium) all correlated with development of any VF defect.

Despite some longitudinal studies in the past having investigated this phenomenon in high myopes, long-term VF defect patterns of development remain unclear. One prior investigation reported 13.2% of HM eyes developing a significant defect over 10 years, while another reported a much higher rate of 42% in a Danish population. The current study’s findings indicate VF defects occurred frequently in highly myopic individuals without pathology. As the study authors relay, this may be due to peripapillary atrophy and/or a tilted optic nerve insertion mapping beyond the normal blind spot on static perimetry; this is corroborated by studies reporting peripapillary atrophy (41.5% to 81.2%) and a tilted optic disc (56.6% to 57.4%) were highly prevalent with HM.

The second most common defect observed was deemed nonspecific, which the authors also predict may be caused by stretching and bending of the retinal nerve fiber layer with myopia progression. Meanwhile, 12.5% of eyes were found to develop glaucoma-like defects of partial arcuate defect, nasal step or paracentral defect. This suggests initial location of optic nerve damage in HM glaucoma may differ from nonmyopic glaucoma, since high myopia alters normal trajectory of retinal nerve fiber bundles temporal to the macula.

With these points in mind, the authors recommend in their paper for IOVS that, “considering the progressive essence of optic neuropathy in HM, it is recommended to incorporate VF testing as a routine assessment, with mean deviation serving as an indicator of functional loss for monitoring HM, especially at the initial visit.”

They also add that “this study highlights the necessity of comprehensive myopia management for monitoring and controlling excessive axial elongation in children and adolescents. Currently, the pathophysiologic mechanism in HM that affects VF is still unclear, and thus our results would be helpful in identifying high-risk individuals and facilitating timely interventions.”

Li C, Chen Y, Yang S, et al. Long-term prediction and risk factors for incident visual field defect in nonpathologic high myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024;65(10):43. |