|

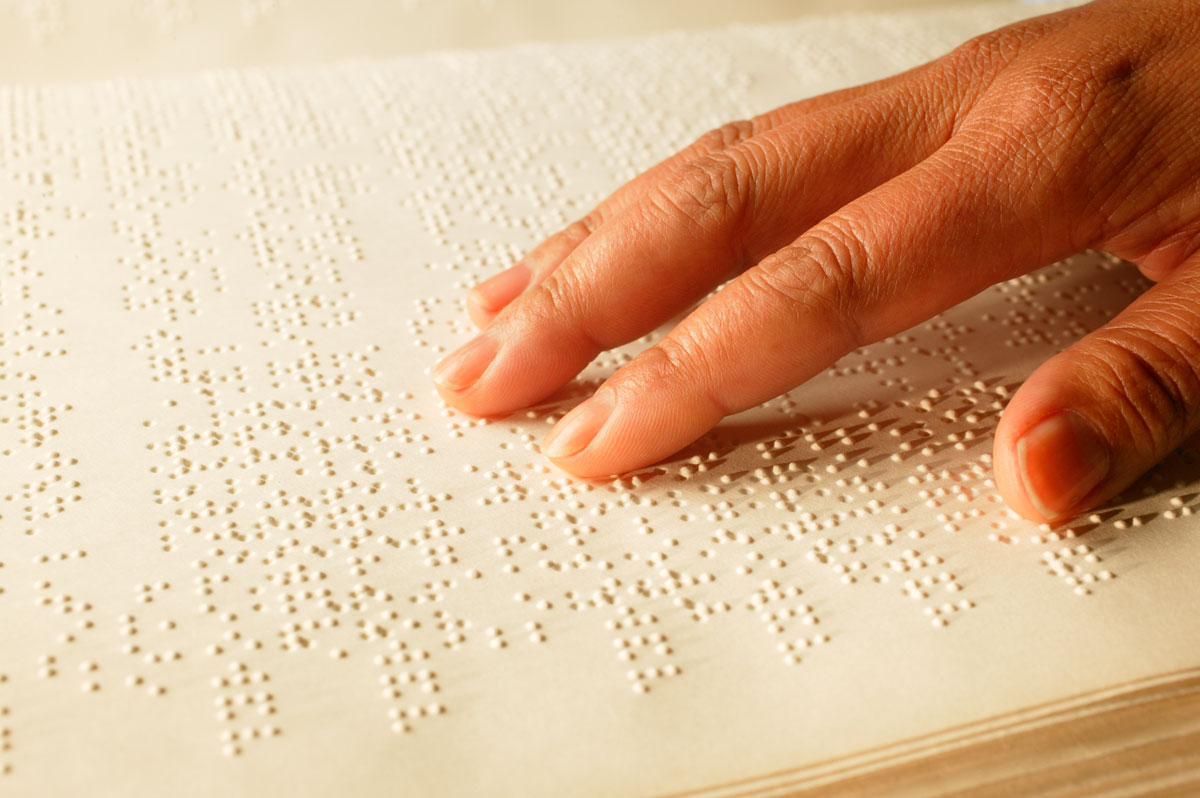

| A study found that many practices lack sufficient resources for those with visual disabilities. Photo: Getty Images. |

Equitable access to healthcare is essential to ensure all patients receive proper care. Though this is legally mandated, the types of accommodations for particular disabilities are often not clearly defined or enabled. Researchers, pointing out the millions of individuals with vision-related disability and impairment, recently authored a paper investigating how physicians practicing in the United States provide accommodations for those with blindness or vision impairment. Despite more than 30 years since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, they found that many physicians aren’t meeting the basic needs of their vision-impaired patients.

“In focus groups [from another study], people with significant vision impairments described needing basic accommodations during healthcare visits,” the authors wrote in their paper. These included, “having clinic staff describe the examination room spaces (to ensure patients’ safety and comfort) and receiving printed materials (e.g., instructions, prescriptions) in accessible formats (e.g., Braille, large font).”

The researchers conducted a nationally representative survey of randomly selected US outpatient clinics across seven specialties and asked about caring for patients with different types of disabilities. They defined vision limitations as “people who are blind or have significant difficulty seeing, even with glasses or other corrective lenses.”

Of the 1,400 selected active board-certified physicians (representing family medicine, general internal medicine, rheumatology, neurology, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery and obstetrics-gynecology), 462 participated in the survey (297 of 457 were male, 65%). The weighted response rate was 61%. The researchers based accommodation performance on always or usually describing clinic spaces and on providing large-font materials. They noted that use of Braille materials was reported too rarely to be included in their analysis.

The researchers reported that only 48 physicians (9.1%) provided both types of accommodations and that 267 (60.2%) provided neither of these accommodations. The researchers noted that 245 (62.8%) non-ophthalmologists and 22 (29.3%) ophthalmologists didn’t provide either accommodation. Only 24% of ophthalmologists provided both accommodations, compared with 8.4% of other physicians.

“This national survey found that approximately three-fifths of physicians practicing in the United States do not always or usually describe the examination room and always or usually provide printed materials in large font to patients with significant vision limitations,” the authors wrote. “More than one-fourth of ophthalmologists reported not providing both accommodations.” They pointed out that except for Braille, none of the four accommodation types cost much time or money. “Therefore,” they wrote, “failure to provide these low-cost, basic vision accommodations is troubling.”

The authors noted that their survey didn’t assess all possible vision-related accommodations practices could make and that physician self-reporting may be subject to positive-response bias, such as overestimating accommodation provision. “We also know little about physicians’ patient panels, including prevalence of disability,” they wrote. Throughout the country, too, it’s difficult to determine vision impairment prevalence.

They concluded that basic accommodations such as large-print materials and describing the clinic can enhance care for patients with vision-related disabilities. “As required under Titles II and III of the Americans with Disabilities Act,” they explained in their paper, “physicians must ask patients which accommodations they would like and seek to comply with their individual preferences.”

Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, et al. Incidence of accommodations for patients with significant vision limitations in physicians’ offices in the US. JAMA Ophthalmology. December 2, 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. |