|

Q:

A patient just released from the hospital after a bout of pneumonia presented with blurred vision and bilateral retinal hemorrhages. What is the best way to manage this case?

A:

“A thorough medical history is critical,” advises Jason Guo, OD, of the Eye Clinic of University Village in Seattle. This patient had just been placed in an induced coma on a ventilator for a week with pneumonia, a history of hypertension and a recent diagnosis of liver damage and anemia. Her medication list included furosemide for liver damage, nadolol and spironolactone for hypertension and prednisone for pneumonia.

“When you see bilateral preretinal hemorrhages, start ruling out diabetic retinopathy (DR), retinal arterial macroaneurysm, hemorrhagic posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) or Terson syndrome,” Dr. Guo advises.

There was no history of diabetes or signs of DR. Bilateral symmetrical arterial microaneurysms typically look very different than this patient’s presentation. There were no signs of a PVD or any vitreous hemorrhage. Terson syndrome was unlikely due to the lack of any associated neurological disease or increased intracranial pressure. Medical eye examination revealed best-corrected acuity of 20/80 OD and 20/200 OS. All other findings were normal except for the fundus.

|

|

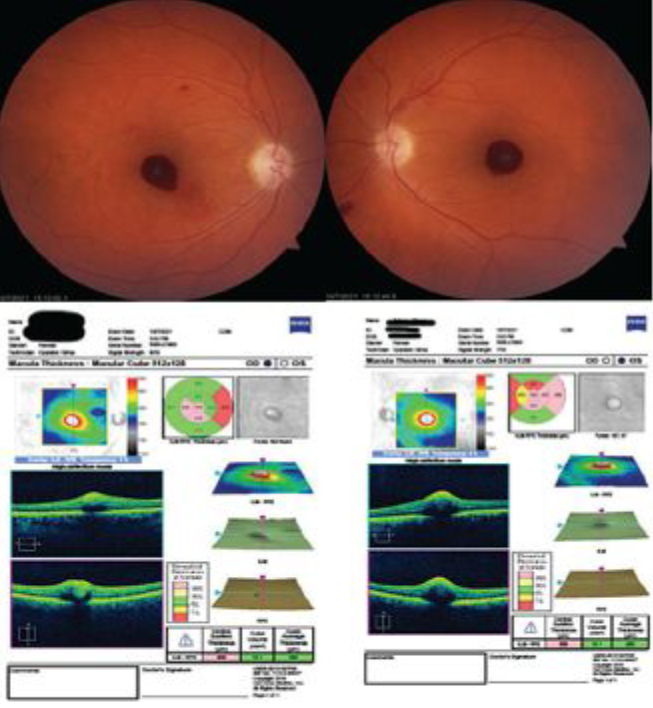

Fig. 1. Fundus exam revealed bilateral preretinal hemorrhages, and corresponding OCT imaging. Click image to enlarge. |

Don’t Hold it In

The macula revealed large preretinal hemorrhages OD and OS that obscured the fovea. There was a small retinal hemorrhage noted two disc diameters superior to the macula, and the left eye showed a larger retinal hemorrhage inferior nasal to the optic nerve. OCT confirmed preretinal/subhyaloid hemorrhage over the foveae, and delineation was appreciated between blood and inner retina OU (Figure 1, above).

Valsalva retinopathy made the most sense; it can occur unilaterally or bilaterally in an otherwise healthy patient.

A Valsalva maneuver is an effort to exhale without letting air escape through the nose or mouth. People often use a Valsalva maneuver during common activities, such as straining to have a bowel movement or blowing a stuffy nose. While Valsalva retinopathy is more commonly seen in males, there is actually no predilection between sex, age or race.1 It is described as a venous vasculopathy caused by a rise in the intrathoracic or intra-abdominal pressure against a closed glottis that ruptures small superficial capillaries.2 It produces a high influx of pressure against the venous system and allows the pressure to pass the thoracic and abdominal pressures into the vessels supplying the eye.3 This increase in pressure in the eye leads to the perifoveal superficial retinal capillaries rupturing, causing a detachment of the internal limiting membrane (ILM).

Don’t Panic

Monitor the hemorrhages, as they usually resolve on their own. That occurred in this patient, with visual acuity of 20/25 OD and OS almost three months after the initial presentation.

If the patient is symptomatic or if the hemorrhage does not improve or resolve within three months, using neodymium:YAG laser can disrupt the ILM or posterior hyaloid, leading to the drainage of blood into the inferior cavity and producing a faster resolution.4,5 A second intervention is pars plana vitrectomy, but this is risky and should be avoided if possible.

While Valsalva retinopathy is a rare side effect of intubation and mechanical ventilation, do not overlook it. Although this patient was on a ventilator for pneumonia and not COVID-19, understanding the ocular effects of intubation can help prepare optometrists for unintended consequences. Patients undergoing general anesthesia of any kind are also at risk.6

Dr. Ajamian is board certified by the American Board of Optometry and serves as Center Director of Omni Eye Services of Atlanta. He is vice president of the Georgia State Board of Optometry and general CE chairman of SECO International. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Simakurthy S, Tripathy K. Valsalva retinopathy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Last updated June 27, 2022. 2. Duane TD. Valsalva hemorrhagic retinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1972;70:298-313. 3. Pstras L, Thomaseth K, Waniewski J, et al. The Valsalva manoeuvre: physiology and clinical examples. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2016;217(2):103-19. 4. Sahu DK, Namperumalsamy P, Kim R, Ravindran RD. Argon laser treatment for premacular hemorrhage. Retina. 1998;18(1):79-82. 5. Schulz-Key S, Carlsson JO, Crafoord S. Long-term follow-up of pars plana vitrectomy for vitreous floaters: complications, outcomes and patient satisfaction. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011; 89(2):159-65. 6. Sunny ACL. Bilateral Valsalva retinopathy after general anesthesia: a case report. J Acute Dis. 2020;9:131-3. |