|

A 53-year-old male presented to the ophthalmic emergency department with flashes and painless decreased vision in the left eye for two days. He had an ocular history of lattice degeneration and an atrophic hole in the right eye. Pertinent medical history includes type 2 diabetes mellitus, for which he takes metformin 1000mg twice daily. He also disclosed occasional use of tadalafil 10mg. He reported no recent viral prodromal symptoms and had no other neurological symptoms such as headache, diplopia, numbness or weakness.

On presentation, his visual acuity was 20/20 OD and 20/70 OS. Intraocular pressures (IOPs) were 18mm Hg OD and 16mm Hg OS. The pupils reacted briskly, but there was an afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. Color vision was full at 14/14 in the right eye and decreased to 1/14 in the left eye with Ishihara testing. Extraocular motility testing was normal without pain. Fundus exam was unremarkable OD and revealed grade 2 optic nerve edema with flame hemorrhage OS. The retina was attached in both eyes.

Currently, differentials for a painless unilateral decrease in vision with disc edema and no signs of intraocular inflammation include an ischemic event, such as anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (non-arteritic vs. arteritic), compressive optic neuropathy, diabetic papillitis, demyelinating disease or an infectious or inflammatory-related etiology.

Arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION), as seen in giant cell arteritis, was considered less likely due to his age and lack of suggestive symptoms such as new headache, temporal pain, jaw claudication, weight or appetite loss, fever and pain seen in polymyalgia rheumatica. Despite being less likely, laboratory testing was ordered—including complete blood count, c-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate—and returned unremarkable, thereby ruling out AION.

|

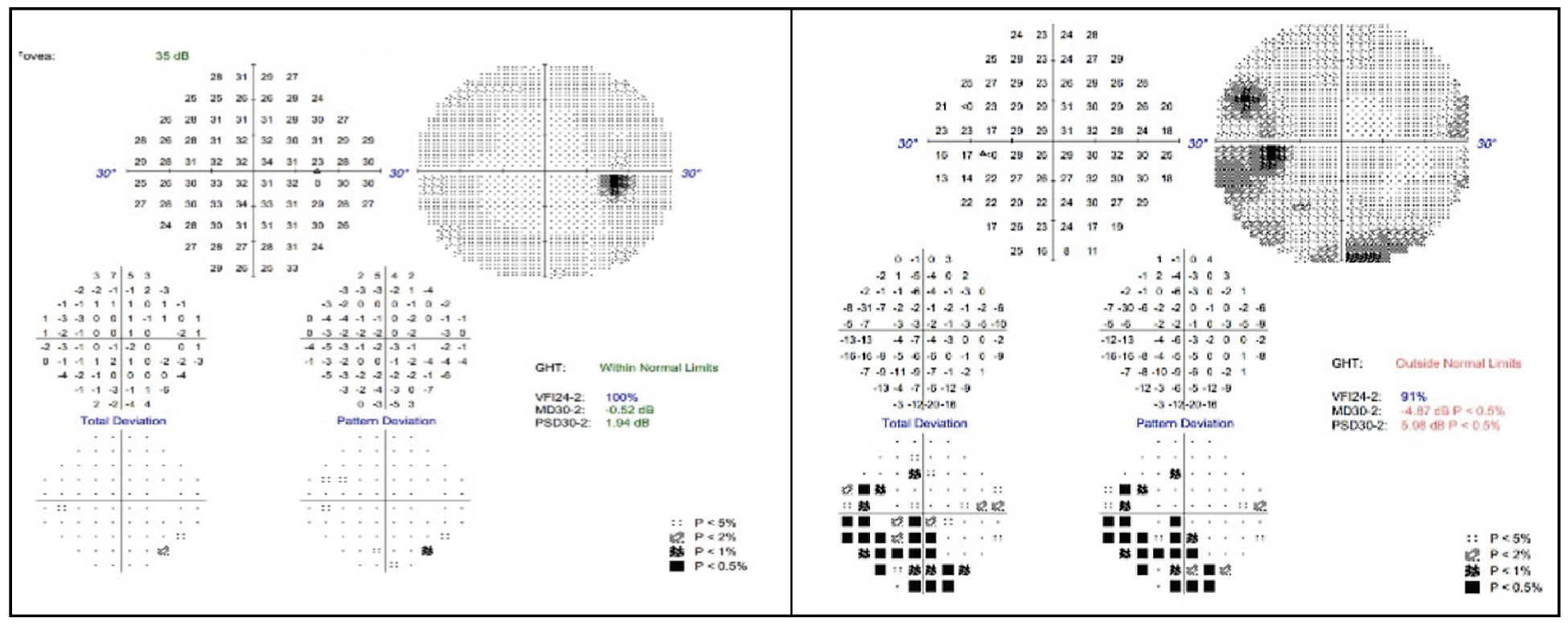

Fig. 1. 30-2 Humphrey visual field of the right eye (left) and left eye (right). Click image to enlarge. |

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbit was completed with and without contrast to look for any lesions or enhancement of the optic nerve. The MRI yielded normal results, making conditions such as compressive optic neuropathy and optic neuritis unlikely. The differential diagnosis list at this point was narrowed to non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), diabetic papillitis or an inflammatory or infectious etiology.

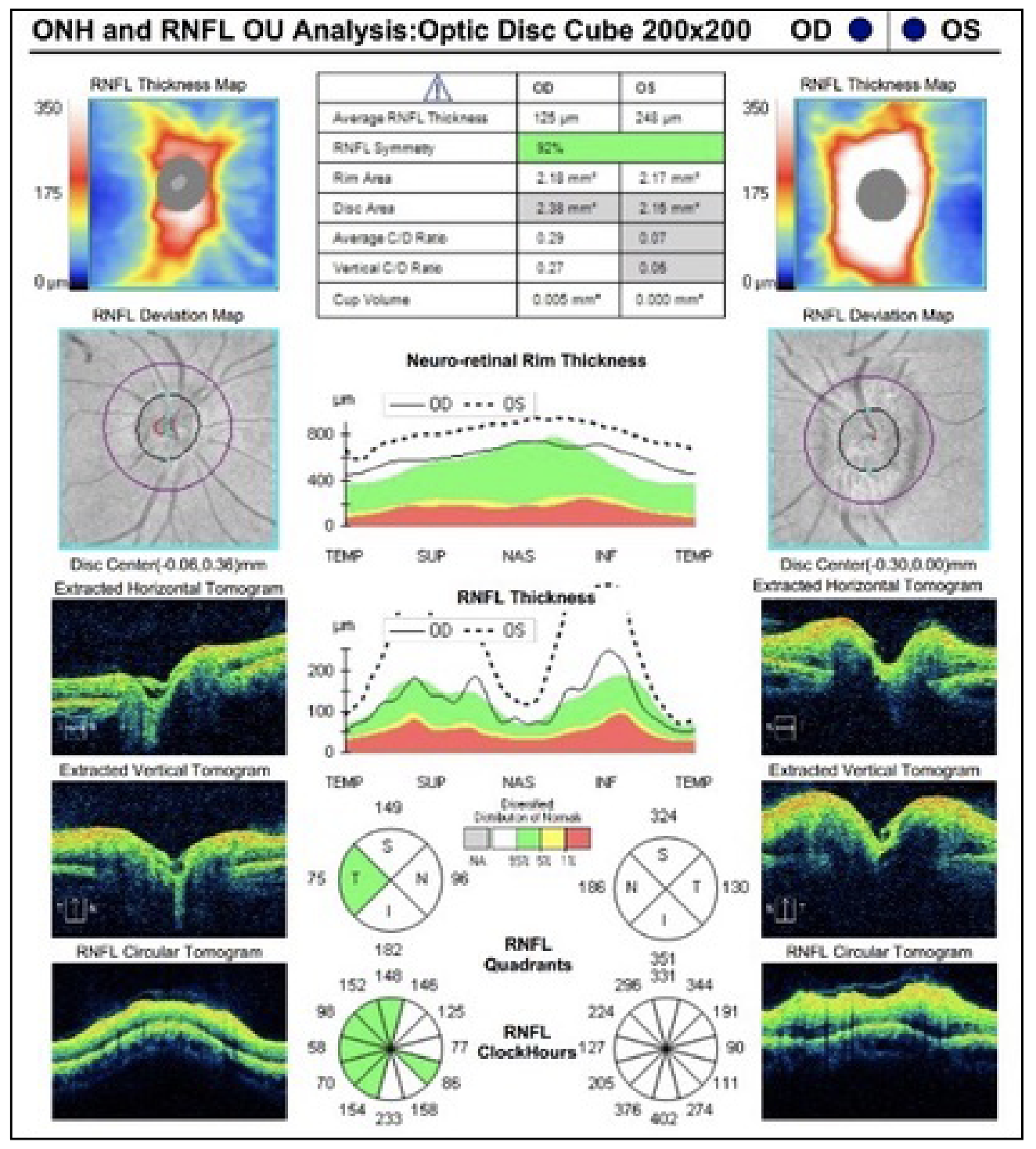

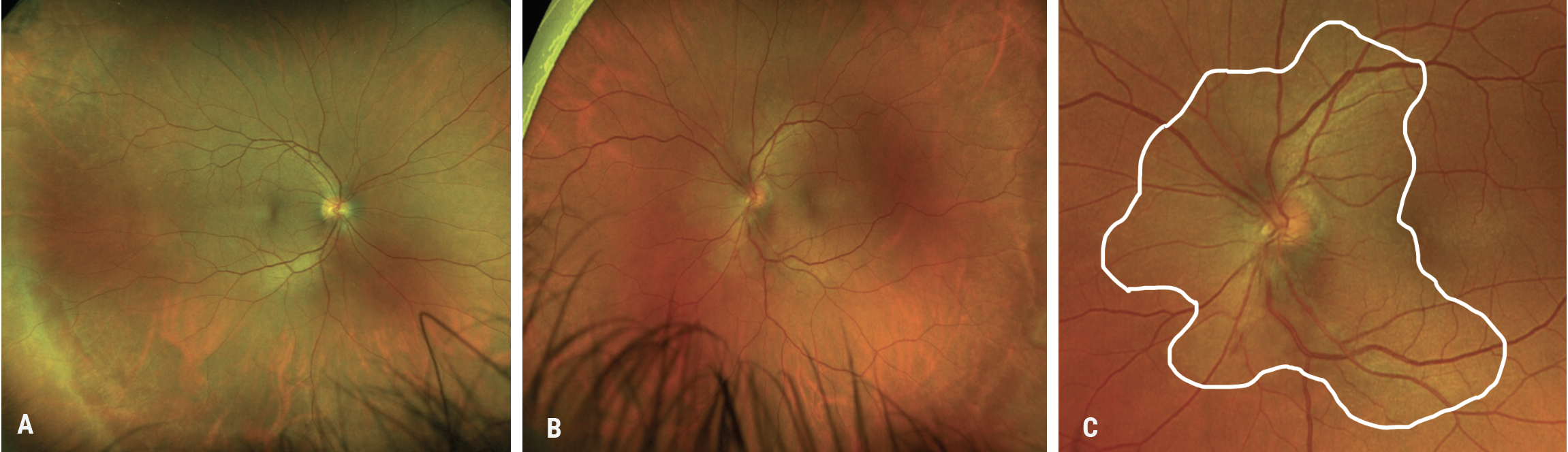

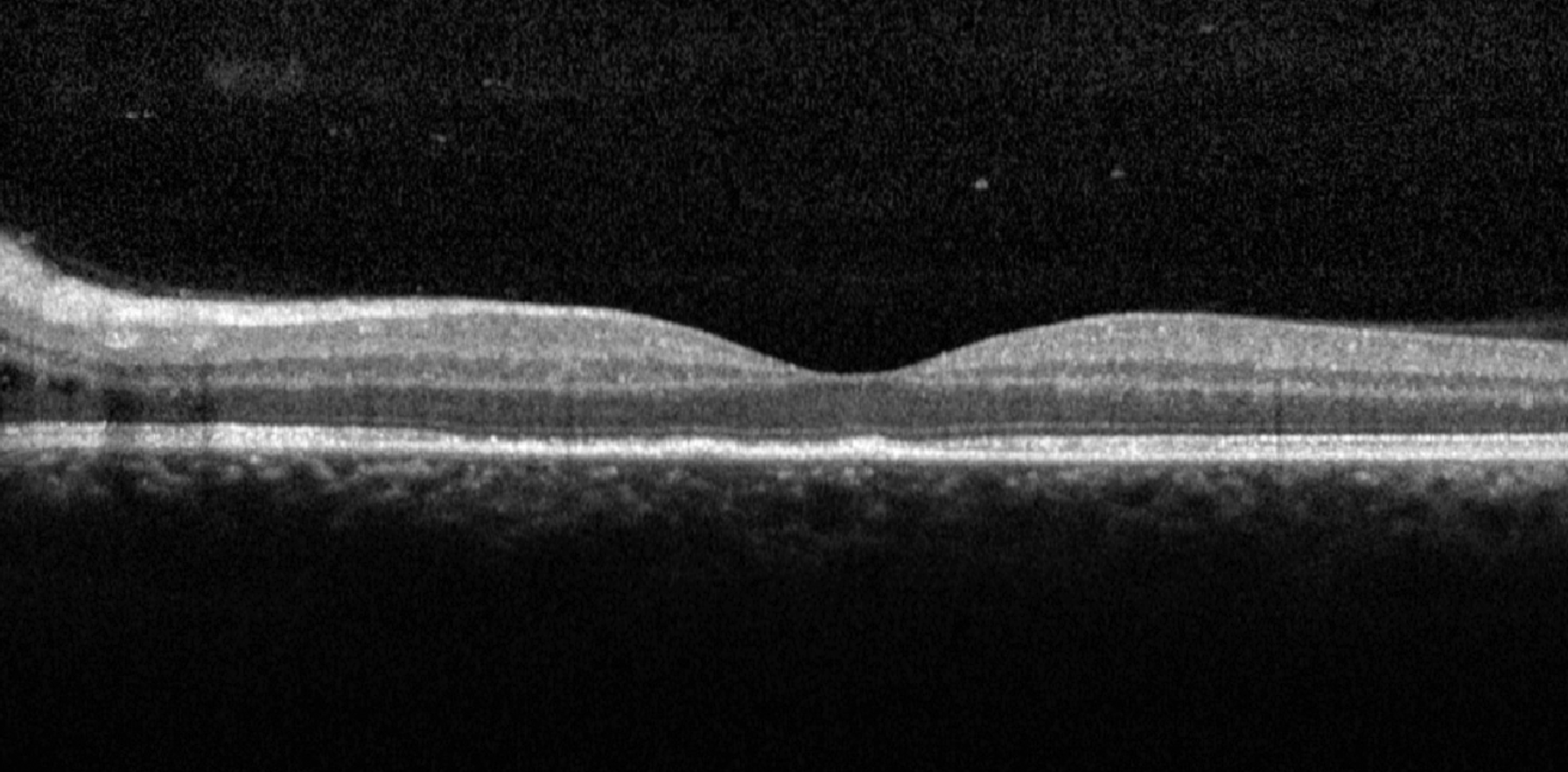

Visual field testing on a short-interval return visit to the neuro-ophthalmology clinic revealed a full field OD and an enlarged blind spot with an inferior scotoma OS (Figure 1). There was notably diffuse thickening of the OS retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) on OCT (Figure 2). The same day, fundus photos revealed an unremarkable right eye (Figure 3A). However, in addition to the optic nerve edema and flame hemorrhage initially seen in the left eye, a new, large, faintly yellowish placoid lesion was seen circumventing the optic nerve (Figure 3B-C). An OCT of the left macula can also be reviewed in Figure 4.

|

Fig. 2. OCT of the RNFL of both eyes. The right eye is unremarkable and the left eye presents with 360 degrees of RNFL thickening. Click image to enlarge. |

Although NAION was the presumed diagnosis initially based on the patient’s age, acute loss of vision and history of using PDE-5, the retinal findings were not consistent with NAION. Therefore, to investigate infectious and inflammatory etiologies, the patient was sent for labs, including Bartonella antibody titers, Lyme antibody titers, angiotensin converting enzyme, serum lysozyme, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rapid plasminogen reagin (RPR), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), toxoplasmosis antibody titers, toxocara antibody titers, comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count with differential. The labs were unremarkable aside from a reactive FTA-ABS and elevated RPR, supporting a diagnosis of syphilis.

|

| Fig. 3. (A) Fundus photo of the right eye with mild peripheral pigmentary changes, but otherwise unremarkable. (B) Fundus photo of the left eye demonstrates a large, faintly yellowish placoid lesion circumventing the optic nerve, along with blurred optic disc margins and a small inferior hemorrhage. (C) Enlarged fundus photo of the left eye allows for better visualization of the yellowish placoid lesion circumventing the optic nerve (outlined in white) along with blurred optic disc margins and a small inferior hemorrhage. Click image to enlarge. |

Verdict and Outcome

Our patient was diagnosed with acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis with optic nerve edema and was admitted to the hospital for intravenous (IV) penicillin treatment and an infectious disease consult. After completing a five-day course of treatment, the patient was seen in clinic for a follow-up, where his vision had improved to 20/20 in both eyes, and there was complete resolution of both the optic nerve edema and visual field defects.

|

| Fig. 4. OCT of the macula of the left eye showing loss of ellipsoid zone and intraretinal edema adjacent to the optic nerve. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Syphilis is known as “the great masquerader” because its clinical presentation can vary widely. The infectious disease is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum and can be transmitted during sexual contact or via congenital transmission in utero, either across the placenta or less commonly by contact with an active genital lesion during delivery.2

Syphilitic infection progresses through four stages and can affect many organ systems. Primary syphilis manifests as a painless ulcer or chancre at the site of inoculation. These lesions are often overlooked and will resolve spontaneously. If untreated, primary syphilis can progress to secondary syphilis roughly six to eight weeks later and presents with generalized symptoms such as fever and malaise, as well as a generalized rash, but may also involve ocular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, renal and neurological symptoms.3 Primary and secondary syphilis will resolve without treatment and enter a latent phase with no clinical manifestations. Approximately 15% to 40% of untreated patients in this stage will progress to the tertiary stage, characterized by the presence of gummas, which are tumors of granulation tissue containing T. pallidum that can affect any body organ, commonly involving the cardiovascular and nervous systems.3

Syphilis can cause inflammation in most areas of the eye at any stage of disease. The anterior segment can present with conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis and syphilitic keratitis. The condition can also manifest in the posterior segment as necrotizing or non-necrotizing retinitis in the macula, midperiphery and peripheral retina and can be associated with vasculitis and vascular occlusion. This case presented with a syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis, which is a yellow inflammatory lesion near the level of the RPE, resulting from invasion of the choriocapillaris.4 These lesions are rare and best viewed with fundus autofluorescence.

The most common ophthalmologic presentation of syphilis is uveitis, which can vary widely in presentation. The inflammation can be granulomatous iridocyclitis (46%), non-granulomatous iridocyclitis (25%), panuveitis (13%), posterior uveitis (8%) or keratouveitis (8%).4 Optic nerve is appreciable in about 20% of cases and presents as perineuritis, optic neuritis, neuroretinitis, papilledema and optic atrophy (late stage).3 Optic nerve edema is thought to be secondary to ischemic or inflammatory processes. Argyll Robertson pupil is a classic finding in syphilis and may result from damage to the ciliary nucleus or to the neuronal connections between the Edinger-Westphal nuclei and the pretectal nuclei. This damage causes the pupils to be miotic and unable to constrict in response to light, but they will constrict in response to near vision phenomenon, termed light-near dissociation.4

The oculomotor pathway can also be affected: in the early stages of syphilis, saccade velocity and accuracy of smooth pursuit movements may be abnormal, and in late stages, a cranial nerve palsy may develop.4

Testing and Treatment

Venereal disease research laboratory and RPR tests are useful in screening for active disease and antibody quantification as a titer level. These tests are sensitive, but not specific, and a positive result should be confirmed with treponemal tests such as FTA-ABS, microhemagglutination assay for Treponema pallidum or T. pallidum-particle agglutination.4 Ocular syphilis may be considered a finding of neurosyphilis; therefore, neurosyphilis protocol may be considered for treatment of all cases. This includes brain imaging and possible lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis, as well as consultation of infectious service.1 The recommended adult regimen for treatment of neurosyphilis is IV aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18 to 24 million units per day (either as continuous infusion or three to four million units every four hours) for 10 to 14 days.1

In conclusion, it is important to always consider less-common etiologies for common clinical presentations, especially if the clinical phenotype morphs or doesn’t fit into the diagnostic box as we expect. Syphilis should remain in the back of our minds often, given its clinically variable presentations, stealthy progression and rise in incidence across the United States.

Dr. Bozung currently practices at Bascom Palmer where she primarily sees patients in the hospital's 24/7 ophthalmic emergency department. She also serves as the optometry residency program coordinator. Dr. Bozung is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and a member of the Florida and American Optometric Associations. She is a founding board member of Young OD Connect and serves on the editorial board for Review of Optometry. She has no financial interests to disclose.

Dr. Mechas received her doctorate of optometry at Ohio State University. Recently, she completed a residency in Ocular Disease at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami and is happy to announce she will be continuing her optometric career at Cincinnati Eye Institute.

|

1. Jones-Vanderleest JG. Neurosyphilis, ocular syphilis, and otosyphilis: detection and treatment. American Family Physician. Published July 31, 2022. www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2022/0800/editorial-syphilis.html. Accessed August 1, 2023. 2. Tudor ME, Al Aboud AM, Leslie SW, et al. Syphilis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. May 30, 2023. 3. Kabanovski A, Donaldson L, Jeeva-Patel T, Margolin EA. Optic disc edema in syphilis. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2022;42(1):e173-e180. 4. Lee AG, Bindiganavile SH, Wiley Z, et al. Ophthalmologic manifestations of syphilis. EyeWiki. Updated July 30, 2022. eyewiki.aao.org/Ophthalmologic_Manifestations_of_Syphilis. Accessed August 1, 2023. Accessed August 1, 2023. |