|

The practice of medicine is a collaborative effort and optometry is no exception. As we discussed in the first installment of this series, comanagement plays a critical role in healthcare delivery and, as primary eyecare providers, ODs should be at the helm of the referral relationship.

While challenging, these conditions can be comanaged successfully and optometrists are in the perfect position to take a leadership role in the care of this patient population.

Comanagement ConnectionsCheck out other articles in this series: Be a Retina Referral Rock Star Keep Glaucoma Care Close to Home |

“It’s important to recognize that there are too few neuro-ophthalmologists to effectively manage the number of patients that present with neuro-ophthalmic disorders,” notes Leonard Messner, OD, an optometric expert in care of neuro-ophthalmic disease and vice president for patient care services at Illinois College of Optometry. “Therefore, it is very important that the general optometrist has a fundamental knowledge and understanding of these disorders to ensure comprehensive patient care.”

Recent research highlights the important role ODs can play in the management of these patients and the need for a comprehensive understanding of these conditions. A prospective, cross-sectional study of cases sent to neuro-ophthalmology subspecialists (from both optometrists and general ophthalmologists) found that the referral diagnosis was incorrect in 49% of cases.1 The researchers reported that 26% of misdiagnosed patients suffered harm, which could have been prevented by earlier referral. In 23% of cases, patients experienced inappropriate laboratory testing, diagnostic imaging or treatment prior to referral.

Clearly, there’s plenty of headroom for optometry to grow its capabilities in triaging neuro cases.

Given the seriousness of these conditions, tackling the management of neuro-ophthalmic patients can be overwhelming. As a part of our comanagement series, this article will help lay the framework for a strong referral relationship as well as offer clinical pearls and practical advice to give ODs the confidence to take on these patients.

|

|

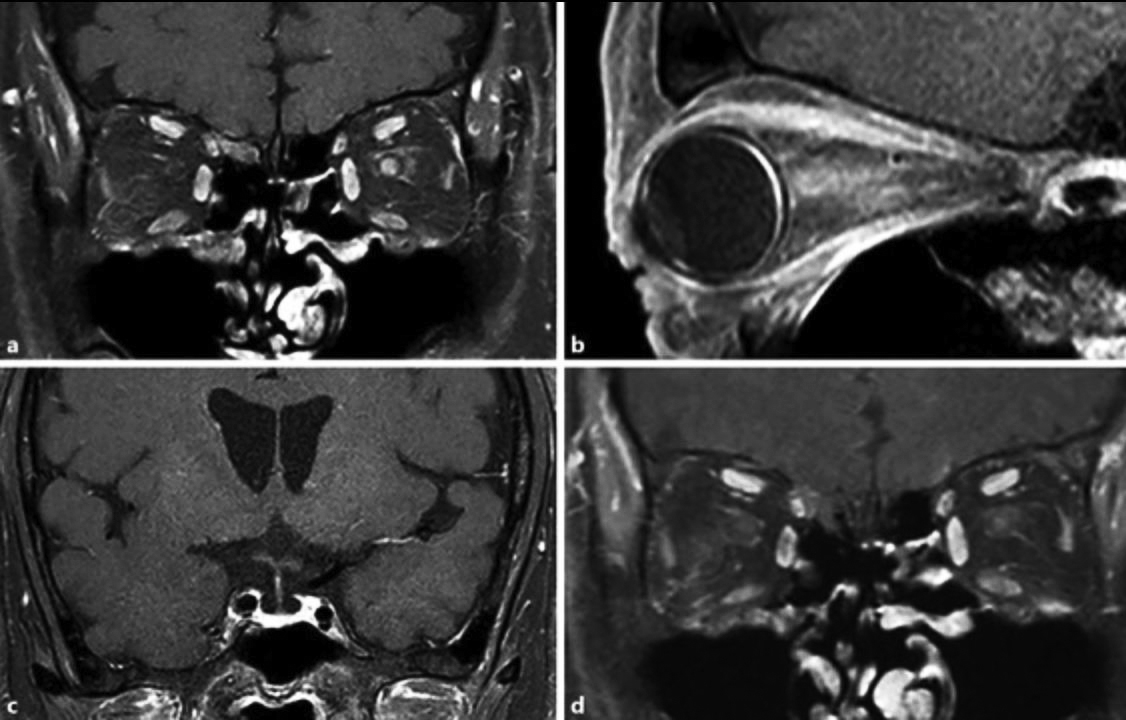

The appearance of optic neuritis on MRI. Optometrists should be comfortable knowing when and why to order neuroimaging work. Photo: Kelly Malloy, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Determining the Referral Pathway

Unlike other areas of optometry, such as cataract or cornea care, the referral pathway for neuro-ophthalmic cases is not always straightforward. Therefore, it is important for ODs to have a clear plan on when and to whom they refer.

Michael DelGiodice, OD, PhD, who practices in New Jersey, has access to neuro-ophthalmologists; however, it can still be challenging to get appointments for patients quickly. “I typically always comanage with neurology,” he explains, noting that neuro-ophthalmologists usually work with neurology as well. “As optometrists, we have the knowledge and skills to work directly with these specialists.”

Comfort level plays a key role in the referral pathway an optometrist chooses to follow, notes Kelly Malloy, OD, professor and chief of neuro-ophthalmic disease at Pennsylvania College of Optometry. “If an optometrist has the confidence to do so, they can directly handle imaging and referral to neurology and neurosurgery,” she says. “Since timely intervention is critical for many neurologic conditions, it is important to take the most direct referral route whenever possible.”

That isn’t to say that neuro-ophthalmology has no role to play. For non-urgent cases, they can serve as a second opinion or additional resource, notes Dr. DelGiodice. In emergency situations, waiting for an appointment with a specialist—whether that’s the neuro-ophthalmologist or neurologist—is not always an option. Those cases require the ODs to make a judgment call and send their patient to the emergency department for immediate care. Once admitted to the hospital, the patient will then be able to more acutely benefit from the knowledge and expertise of neuro-ophthalmologists, neurologists and other specialists as needed, according to Dr. Malloy.

In some cases, the best specialist may not be neurology related. For instance, Dr. DelGiodice will refer a patient with unilateral disc edema or signs suggestive of incipient disc edema to a retina specialist for immediate, same-day fluorescein angiography (FA). “These cases obviate the need for neuro-ophthalmic referral because the FA will elucidate the seat of the pathology,” he notes.

|

|

As many as 60% of myasthenia gravis patients, such as this one, present with ptosis and diplopia. Photo: Christopher Suhr, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Fostering Strong Relationships

Like any comanagement relationship, building a partnership based on mutual trust and respect is vital to success. This begins by finding specialists who not only have strong clinical skills but also value the important role optometry plays. Without this, a true comanagement relationship that benefits both patients and providers is not possible.

“Effective comanagement requires a high level of coordination between providers, whether that is the neuro-ophthalmologist, neurologist or primary care provider,” notes Dr. Messner. “Building and maintaining a strong relationship depends on communication.”

Direct, consistent communication helps take the guesswork out of case management. “Nothing can replace picking up the phone and communicating peer-to-peer. This ensures the relationship is a two-way street and everyone is on the same page,” emphasizes Dr. Messner. “That is the art and science of medicine. It is the essence of taking care of people properly.”

Given the complex, and often subtle, nature of neuro-ophthalmic conditions, ODs must feel comfortable working collaboratively, but finding the right specialist can be a challenge. Visiting physicians at their office, whether by appointment or dropping off your resume and making a quick introduction, can be a good way to build connections, according to Dr. DelGiodice.

“Writing comprehensive letters is another way to enhance the referral relationship,” he says, noting that this is an effective approach to showcase your own skills and knowledge of neurologic conditions. Dr. DelGiodice also suggests taking it a step further and calling the office to discuss the case as well. “Comanagement becomes easier as you build that trust and both providers are confident in one another’s abilities.”

Optimizing the Approach to Neuro-Ophthalmic Care

Understandably, many neuro-ophthalmic conditions can pose a challenge for optometrists. Neuro abnormalities can present within any of the three main components of the eye examination (afferent assessment, efferent assessment and ocular health assessment) and these conditions often have features that overlap with a variety of other ocular and systemic conditions. Determining when and when not to refer can be a difficult task.

Common neurologic complaints optometrists may encounter include diplopia, vision loss or visual disturbances, and headaches. Facial and lid abnormalities, such as ptosis, proptosis, facial weakness, head turn or tilt, and blepharospasm, can also indicate neurologic eye disease.2

As with any type of condition, a detailed history is a vital first step, followed by a comprehensive eye exam. This should include blood pressure measurement, relative afferent pupillary defect assessment, measuring pupils and eyelids, visual field testing and OCT.3 In addition, a cursory neurologic examination can also help significantly with localization of the abnormality.

“Optometrists should always consider that every patient might have a neuro-ophthalmic disease process,” suggests Dr. Malloy, who notes that while it may be obvious among patients who present urgently, ODs also need to pay attention for signs of neuro-ophthalmic disease in patients who present for routine care without any specific complaints. “It is important to comprehensively assess the afferent and efferent visual systems as well as the ocular health status of every patient.”

Navigating when a referral is necessary and when it isn’t depends on a fundamental understanding of these conditions as well as the necessary testing. “ODs must be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of underlying neurologic disease and conduct appropriate tests,” Dr. Messner says. “And, when needed, work hand in hand with either neuro-ophthalmology or neurology for the betterment of the patient.”

For example, there are number of vision and eye movement problems associated with multiple sclerosis, including optic neuritis and brainstem motility abnormalities. The general optometrist should be able to recognize these issues and work with neurology to evaluate and manage these individuals effectively.

Once patients have been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, the OD continues to play a role in their long-term comanagement. For example, communicating follow-up OCT and visual field findings to neurology can help them determine stability and adjust treatment plans as needed.

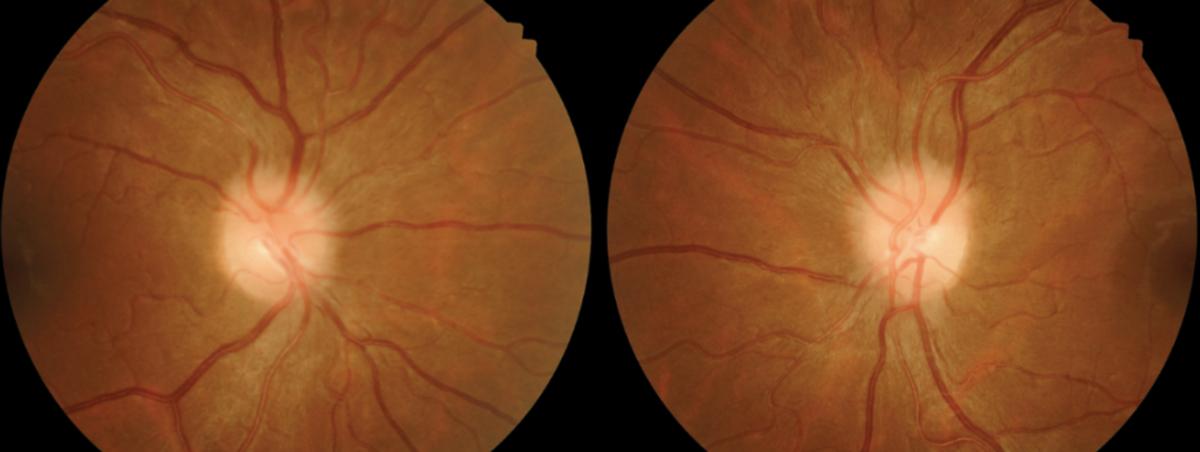

A condition that Dr. Messner sees frequently is idiopathic intracranial hypertension. “A key finding associated with this disease is papilledema,” he says. “So, these are individuals that invariably are initially seen by optometrists with comanagement by neurology.”

However, this does not mean the optometrist’s role ends with the referral. Someone still needs to be following the patient’s vision and doing regular visual fields and OCTs, notes Dr. Messner. “Neurologists, to a large extent, do not have the fundamental knowledge of the visual field or OCT interpretation, and this is where optometry must take the lead. This is comanagement in its truest sense.”

When a condition necessitates a referral, optometrists should maintain relationships with both the specialist and patient to ensure they continue to take a leadership role in care. Communication with the neurologist or other specialists is crucial throughout follow up.

“I make a point to schedule an appointment with my patient after they see the neurologist and I will continue to manage their visual challenges,” explains Dr. DelGiodice. “This can include, for example, running OCTs or visual field tests. The results of all of those images and testing are then sent to the neurologist. While they are taking care of the chronic management of a patient’s disease, I am following the patient and continuing to manage their visual needs.”

One of the most challenging—and potentially daunting—aspects of neuro-ophthalmic comanagement is the life-threatening implications some conditions may have. Optometrists must be able to recognize when a situation is an emergency and when it is not. Conditions that require immediate referral to the emergency department include aneurysm, giant cell arteritis, acute stroke, papilledema, pituitary apoplexy and carotid artery dissection.3

In these cases, timing is critical; ODs need to be ready to take immediate action and send their patients to the emergency department. Referring to their primary care provider or another specialist could cost the patient valuable time. “Optometrists have a significant role to play in recognizing emergency cases and acting accordingly,” explains Dr. Malloy, who suggests that ODs stay current on the latest recommendations as well as participate in ongoing continuing education to ensure they have the confidence to make these calls.

Recommendations and standards of care can change from the time an OD graduates from optometry school, notes Dr. Malloy. “More recently, we have seen this with how acute transient vision loss and symptomatic retinal emboli are managed,” she says. “We now understand that these conditions should be treated the same as acute stroke, requiring the patient be sent immediately to an emergency department of a hospital with a dedicated stroke center.”

|

|

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is fairly commonly diagnosed by optometrists—and it’s incumbent on them to coordinate care, says Dr. Messner. Photo: Joseph Sowka, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Effective Patient Communication

A sometimes difficult but important aspect of comanagement is patient communication. This involves not only explaining a diagnosis or reason for referral, but helping them through the process of seeing a specialist.

When discussing neurological concerns, ODs must strike a balance between conveying the seriousness of a condition without unduly alarming their patient. “You don’t want to overstate the diagnosis,” suggests Dr. DelGiodice, “because the majority of the time you’re not going to have a definitive answer yet.”

Conducting a Comprehensive Neuro Exam4The neurologic exam is a vital part of comanaging neuro-ophthalmic conditions and can easily be conducted in the optometry office. Key components of the exam, include:

|

Using words like proactive or preventive while describing your recommendations and actions can be a good approach with patients. “The key is to communicate,” says Dr. DelGiodice. “Explain the process and let them know that you will be following up with them after they see the specialist.” When patients hear you taking the lead in coordinating their care, they tacitly acknowledge that your role in their care will continue even as other doctors become involved.

“There’s a tendency to think that if you scare someone [with a dramatic description of the condition], they’re actually going to follow through” and urgently see a specialist, Dr. DelGiodice continues. “However, in my experience, it has the opposite effect. Often, the patient will shut down and won’t process what you are saying.”

Handling emergency cases requires a nuanced approach, he notes. An emergent situation still doesn’t mean you should scare your patients, but you do need to emphasize that moving quickly is in the best interest of their health and overall well-being.

Dr. DelGiodice goes the extra mile to make sure his patients have support, especially when they have to contend with a visit to the emergency department. He provides them with a note for the doctor as well as his phone number and tells them to call if they have any questions or need help.

The optometrist should also call the hospital and, if possible, speak with either the neurologist on call, emergency department doctor or at least the triage nurse to explain the patient’s presentation and why it warrants emergency evaluation, suggests Dr. Malloy.

When a patient adamantly refuses to go to the emergency room, Dr. DelGiodice will follow up with the patient as well as connect with one of their other providers. This may not be their PCP but rather the person they see most frequently, such as their cardiologist. “In these situations, sending your patient back to a provider they haven’t seen in two years is not an effective approach,” he notes.

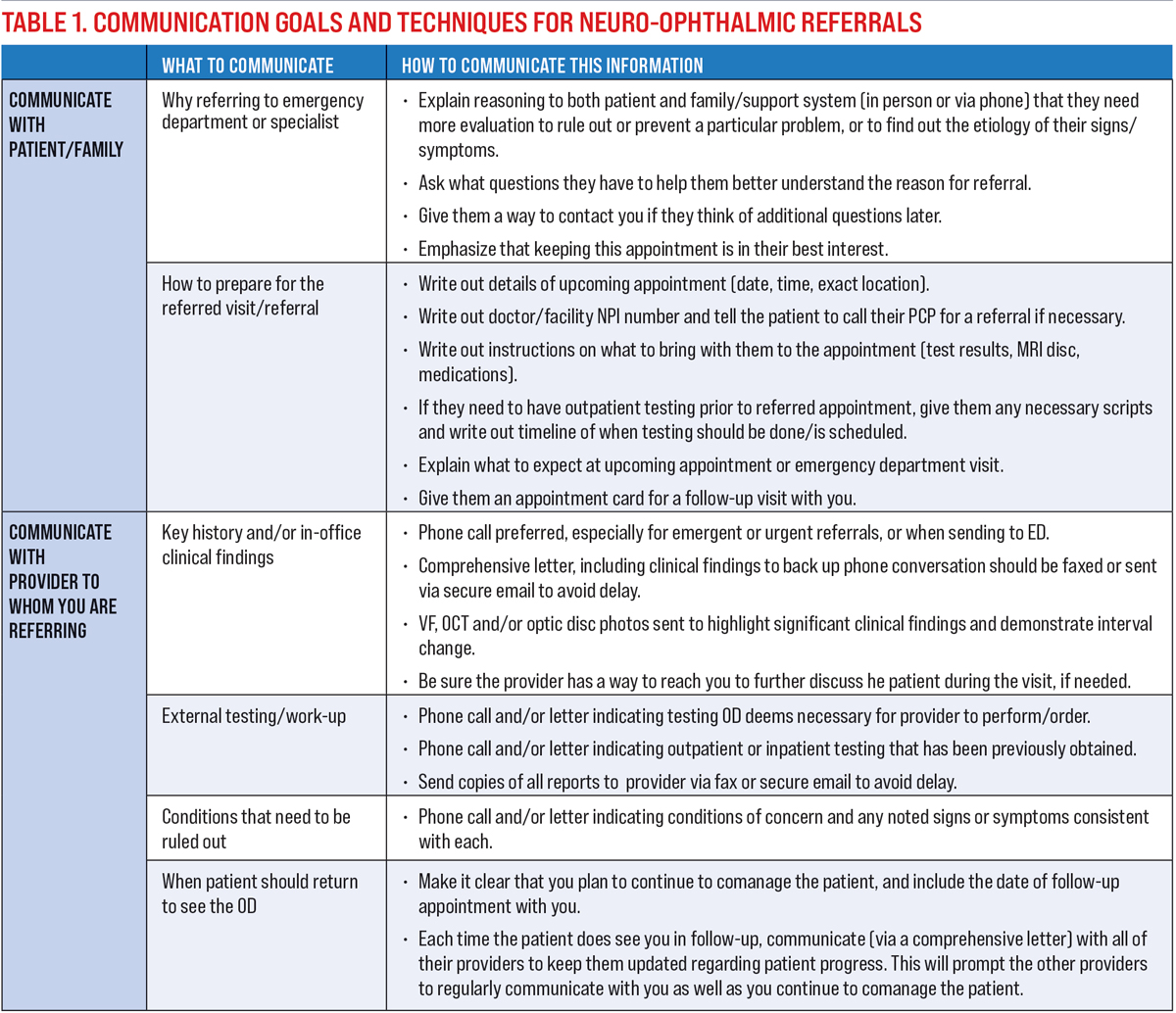

Table 1, developed by Dr. Malloy, lists many specific points to communicate to patients and comanaging providers.

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Ongoing Education & Growth

Given the wide range of neuro-ophthalmic conditions as well as their complex nature, continuing education and professional growth is necessary for the ongoing enhancement of your practice.

One way to build your confidence when assessing these cases is through mentorship. “Fostering a mutual relationship with someone who does neuro work, ideally a fellow optometrist, is an excellent way to grow your skills,” notes Dr. DelGiodice. “This will help you become more comfortable with timing and diagnosis of these conditions.”

An area where mentorship could be very useful is double vision, according to Dr. DelGiodice, who notes that given the subtlety of this issue, building up skills on your own can be very challenging. Optometrists should also continue to develop their ability to interpret visual field and OCT findings for patients with neuro-ophthalmic disorders, notes Dr. Messner, who emphasizes the importance of keeping up with the latest technologies.

“It’s fascinating to see how technology is evolving, particularly in the area of OCT,” he says. “We’re able to look at the structure of the optic nerve and retina almost down to a cellular level. It’s been said now that we really need to be looking at OCTs the same way that neuroradiology looks at the MRI and I think that is absolutely true.”

Another key component related to the care and comanagement of these patients is knowing which neuroimaging studies to perform. Any OD who wants to take this aspect of their practice to the next level must devote significant time to honing these skills.

Key Takeaways

|

As mentioned above, optometrists should play a central role in the management of these patients, including ordering imaging. With a shortage of neuro-ophthalmologists, especially in more rural areas, ODs should be prepared to take charge of these patients. “The optometrist should be fundamentally involved in ordering neuroimaging studies, MRI and CT scans,” explains Dr. Messner.

“We don’t want to abrogate this responsibility to the primary care physician or the general ophthalmologist,” he continues. “As optometrists, we are the ones seeing the patient and we have the greatest understanding of their clinical manifestations; therefore, it is our responsibility to take the lead.”

Optometrists need to know which imaging studies correlate with which conditions. Who needs a CT? Does the patient require an MRI with or without contrast? Once you have identified the condition, ODs must feel comfortable directing the imaging center. “Proving localization and directions for the proper imaging study is crucial,” says Dr. DelGiodice. “The final part, which can be more challenging, is reviewing the scans.”

Over time, the OD’s experience will grow, and they will become more comfortable reading the scans. Some may ask, is this a necessary step? “I think it is important because it is our field,” notes Dr. DelGiodice. “If you’re comanaging with a neurologist, you want to know what you are looking at. This step may be less necessary if you are working with a neuro-ophthalmologist; however, I believe improving your skills in this area will only enhance your practice.”

Dr. DelGiodice makes a point to request the discs and review all of the scans. If questions arise, he will connect with the neuroradiologist. He acknowledges that not everyone has direct access to this specialty. However, the OD should always have the ability to call and speak with the reading radiologist regardless of where they work and/or where the study was performed. In addition, comanaging with neurology or neuro-ophthalmology can allow for another opinion regarding neuroimaging findings when needed.

With limited access to neuro-ophthalmologists as well as cases that often require timely intervention, it is critical that ODs be positioned as leaders in care for patients with neuro-ophthalmic conditions. Effective comanagement begins with ODs and their desire to explore what are often complex and challenging cases.

“Most patients present with subtle clinical signs, so you have to be able to carve out the time to carefully evaluate these cases and you have to be curious,” concludes Dr. DelGiodice. “Curiosity is paramount when it comes to managing these conditions.”

1. Stunkel L, Sharma RA, Mackay DD, et al. Patient harm due to diagnostic error of neuro-ophthalmologic conditions. Ophthalmology. March 10, 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. 2. Trottini M, DelGiodice M. An Intro to Neuro. Review of Optometry. 2015. www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/an-intro-to-neuro. 3. Malloy K. 10 Tips and Helpful Hints for Neuro-ophthalmic Disease. Review of Optometry. 2018. www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/10-tips-and-helpful-hints-for-neuroophthalmic-disease. 4. Maglione AK, Seidler K. The Neurologic Exam, Step-by-step. Review of Optometry. 2019. www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/the-neurologic-exam-stepbystep. |