Prism can be a powerful treatment for many conditions and for many patients, specifically for those who suffer from asthenopia or diplopia. Although successfully prescribing it can sometimes seem like a time-consuming and daunting task, the following tips can help you smoothly incorporate the use of prism for binocular vision conditions into your practice for the best outcomes.

Identifying Prism Candidates

One of the most important aspects of successfully prescribing prism is choosing patients who will benefit the most from it. The first hurdle is ensuring your patient is comfortable with wearing spectacles. Although small amounts of vertical prism can be prescribed in contact lenses, patients who need prism usually have to wear it on a spectacle lens. Although this seems like a very basic requirement for prism use, it can present an obstacle if not done appropriately or at all. Patients who wear contact lenses the majority of the time or who have undergone refractive, cataract or strabismus surgery may not be happy with the idea of moving or going back to spectacle wear even if it relieves asthenopia or diplopia. Educating patients on the benefits of prism wear is key in helping get them on board in these cases.

Patients with non-strabismic binocular vision disorders—such as divergence insufficiency, basic esophoria and vertical heterophoria—can often benefit from treatment with prism, particularly relieving prism, while others—including those with convergence excess, convergence insufficiency, divergence excess or basic exophoria—are better managed with other treatment modalities, such as vision therapy or lenses.1 An option for prism patients is prescribing prism to relieve diplopia and asthenopia and concurrently having the patient do vision therapy to attempt to decrease or eliminate the amount of prism needed.

|

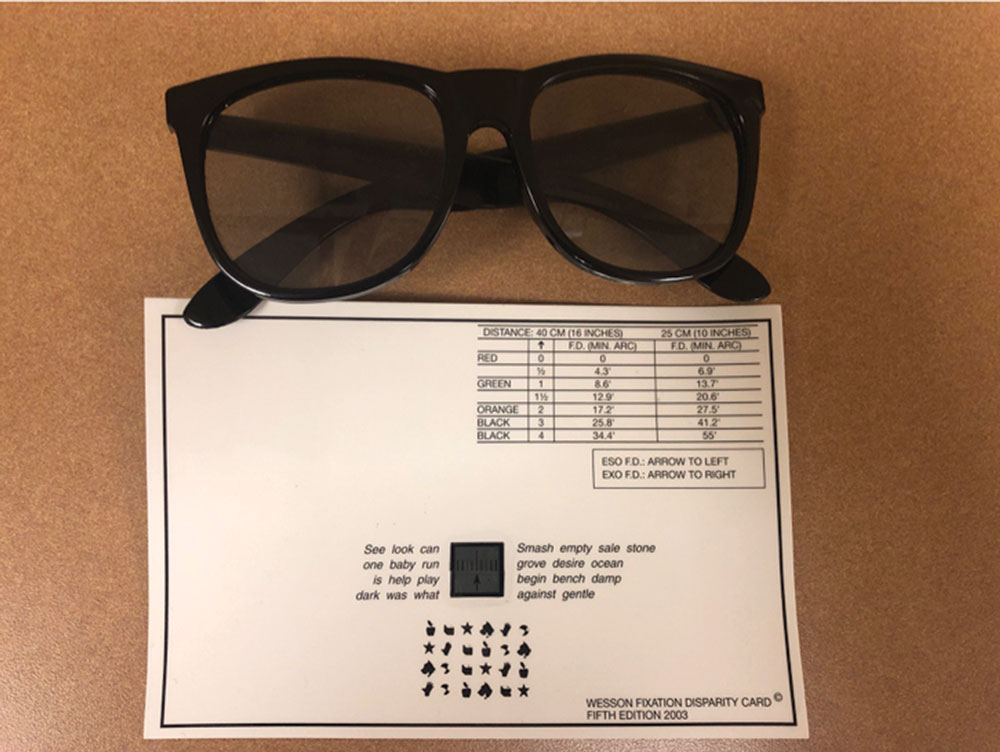

| Use Wesson cards to measure fixation disparity and the associated phoria. |

Divergence Insufficiency. Divergence insufficiency patients are often symptomatic for diplopia and asthenopia at distance and may present with a decompensated distance phoria. Divergence insufficiency is associated with systemic and neurological disorders, so we must rule out any underlying conditions that may be causing it. Any patient presenting with divergence insufficiency and neurological symptoms should undergo a full neurological evaluation and imaging.2

Vision therapy aims to decrease symptoms of vergence anomalies by increasing the compensating fusional vergence range (base-in for esophoria and base-out for exophoria). The normal amount of fusional divergence ability at distance is lower than that of fusional convergence ability, making it challenging to sufficiently increase ranges to compensate for esophoria or esotropia at distance. This combined with the success of prism treatment in patients with divergence insufficiency makes prescribing prism the ideal initial treatment for this condition. One study successfully treated 87 patients with divergence insufficiency between two and 18 prism diopters (PDs) with prism with none of the patients in the study requiring additional treatment or surgery.3 Another study found that 100% of patients with divergence insufficiency (30 patients) had success with prism.4

Basic Esophoria and Exophoria. Prism can be used alone or in combination with vision therapy to treat basic esophoria and exophoria.

Vertical Heterophoria. Another condition commonly treated with prism is vertical heterophoria, or vertical strabismus. Vertical deviations often cause patients to experience significant symptoms even when the deviation is small. Our normal supraduction and infraduction abilities are limited, so improving these ranges to compensate for a vertical deviation can be challenging. The difficulty of training vertical vergence ranges along with the success in treating vertical deviations with prism make prism the most appropriate initial management tool in these patients. Retrospective case reviews of patients with an acquired hyper deviation secondary to a superior oblique palsy found that 76% to 92% of participants were successfully treated with prism alone.5,6

These patients often present with horizontal and vertical deviations. In many of these cases, the initial management strategy is prescribing vertical prism.1 Often, if the vertical deviation is decreased or eliminated, the patient may be able to comfortably fuse the horizontal deviation. If the patient is still symptomatic, combining prism and vision therapy may help improve convergence and divergence ranges. When considering whether it is appropriate to prescribe vertical prism for a patient with combined horizontal and vertical deviations, particularly for a patient with intermittent strabismus, first identify whether the vertical deviation is primary or secondary.

A primary vertical deviation is the same in presence and size whether the patient is strabismic or aligned. A secondary vertical deviation, on the other hand, presents when the patient’s eyes are strabismic but disappears when the patient aligns their eyes to the ortho position.7 Secondary vertical deviations are common in strabismic patients, particularly in those with intermittent exotropia. If an intermittent horizontal strabismus patient has a primary vertical deviation, vertical prism may help improve their ability to fuse the horizontal deviation. In patients with a secondary vertical deviation, however, vertical prism is not an appropriate treatment. Rather, treatment for a secondary vertical deviation should aim to improve horizontal sensory and motor fusion through vision therapy so the patient is not in the strabismic position as often, thus eliminating the vertical deviation.

Convergence Insufficiency. Prisms aren’t as successful in treating convergence insufficiency and are used less frequently than other treatment modalities. The most effective treatment for this condition is office-based vision therapy, but prism can be considered in patients who are unable to undergo this treatment modality.1,8 A study did not find a significant difference in the signs or symptoms of children with convergence insufficiency who wore base-in prism compared with children who wore placebo lenses.9 Although prism has not been shown to be beneficial in children with this condition, adult presbyopic patients with convergence insufficiency may benefit from prism treatment.10,11

Strabismus. While patients with strabismus often benefit from prism wear, it is important to first determine whether a strabismic patient is fit for treatment with prism by evaluating their potential for sensory fusion and whether the addition of prism will improve their sensory fusion status. Prism is prescribed to these patients to partially or completely eliminate the motor demand so they are able to fuse. If a patient does not have good potential for sensory fusion, then the assistance that prism gives to the motor system won’t allow for normal fusion, and it doesn’t make sense to prescribe it.

Sensory Anomalies. Patients with sensory anomalies, such as suppression or anomalous correspondence, cannot be treated with prism until they have been eliminated. Testing for suppression and anomalous correspondence can be easily done with the Worth Dot test. The test can identify and characterize suppression based on the room’s illumination and the distance of the test from the patient. If a patient sees four dots in free space or gives a diplopia response but is able to fuse with prism, perform a unilateral cover test. If no movement is seen on the unilateral cover test, the patient has normal correspondence. If the patient gives a fusion response with or without prism but movement on the unilateral cover test is seen, then anomalous correspondence is suspected and relieving or corrective prism is not an appropriate management option. The most successful prism cases are often patients who have intermittent strabismus and good potential for normal fusion or patients with strabismus who have not developed any sensory anomalies. They tend to be older pediatric or adult patients with new-onset or decompensated strabismus. After these patients are evaluated for any underlying systemic or neurological disease, which must always be ruled out in any case of new-onset strabismus, they are often good candidates for a prism prescription.

|

| This patient is wearing a Fresnel membrane prism on their glasses. |

Prescribing Prism

After identifying a patient who stands to benefit from a prism prescription, the next step is deciding how much prism to prescribe. There are many different ways to do this, but the best method to use depends on the type of binocular vision disorder for which you are prescribing.

Prescribing relieving prism for horizontal, non-strabismic, binocular vision disorders can be done by calculating Sheard’s or Percival’s criteria by using clinical data or analyzing fixation disparity and determining the associated phoria.1 At near, fixation disparity and the associated phoria can be found with a Wesson card. While viewing the card, the patient reports what color line the black arrow is aligned with. The patient is also instructed to keep the words around the lines clear to control accommodation. To determine the associated phoria, add prism in the appropriate direction until the patient reports that the arrow is aligned with the center line. At distance, the American Optical vectographic slide is commonly used to determine the associated phoria. Electronic charts are now routinely used in practice, and many of them have an available distance target for determining fixation disparity and the associated phoria.

The preferred method for prescribing prism for vertical heterophoria is determining the vertical associated phoria.12 This can be done at near using the Wesson card or at distance.

Case #1

A 25-year-old female presented complaining of double vision and headaches that worsened with prolonged near work. Her medical history was unremarkable, and her ocular history was remarkable only for low myopia, for which she wore glasses.

Upon examination, she had a small exophoria and a 3 PD right hyperphoria at distance and near. Her vertical associated phoria, which I determined using the Wesson card, was 2 PD right hyperphoria. I trialed 2 PDs of base-down prism using a Fresnel prism over the right eye and dispensed at the initial visit. During a follow-up examination three months later, the patient noted increased comfort and resolved diplopia and headaches while wearing the Fresnel prism. A new prescription for prism lenses was dispensed to the patient at the follow-up examination.

Patients with constant strabismus may need corrective prism, or an amount of prism that completely neutralizes their strabismus, in order to obtain good levels of fusion. Relieving prism is often prescribed for patients with intermittent strabismus and sometimes for those with constant strabismus. This decreases the motor fusion demand, allowing the patient to fuse more comfortably. Prescribing for some patients with intermittent strabismus can be done by using Sheard’s or Percival’s criteria or determining the associated phoria as with heterophoric patients.

Another method used for prescribing for patients with intermittent strabismus, particularly for those who have difficulty with fusion in free space, is Caloroso’s Residual Vergence Demand (RVD).7 RVD criteria look at the direction and size of the deviation and determine how much residual vergence demand the patient should have after prescribing relieving prism. RVD states that esotropic patients of magnitude 6 to 20 PDs should be left with 4 to 6 PDs of residual vergence demand. Patients with 20 to 30 PDs of exotropia should be left with 10 to 15 PDs of residual vergence demand, and patients with a vertical strabismus of 3 to 10 PDs should be left with 2 to 4 PDs of residual vergence demand.7 RVD is best used in patients who have vergence ranges that have been maximally trained through vision therapy but still need prism to maintain binocular vision in free space.12

Determining how much prism is required for improved fusion, or “fusion prism,” is another method for prescribing prism for your strabismic patients. Fusion prism is the minimum amount of prism needed to see a change from diplopia or suppression to normal binocular vision.12 To determine prism using this method, use the Worth Dot test to find a preliminary prism amount. While viewing the Worth Dot test, prism is gradually increased until the patient reports fusion. You can also use Random Dot Stereo (RDS) testing to determine fusion prism. Prism is gradually increased until a patient is able to appreciate the forms on the RDS test. After a preliminary prescription of fusion prism is determined, it is recommended that you trial frame the patient and have them look around to see if they experience any diplopia when viewing objects in the room. If your patient is still experiencing diplopia, additional prism may be needed to help them achieve fusion.

Case #2

A 5-year-old female initially presented for a strabismus and amblyopia evaluation. She had been previously diagnosed with esotropia and amblyopia but was not currently wearing any correction.

On initial presentation, her best-corrected visual acuities were 20/40 OD and 20/25 OS. Her cover test revealed a 25 PD constant right esotropia with a 2 PD constant right hypotropia. Her cycloplegic retinoscopy was +3.00sph OD and +2.25sph OS. I prescribed glasses (+3.00 sph OD, +2.25 sph OS) for the patient, and she returned for follow-up care, eventually patching and undergoing vision therapy for her amblyopia.

Through her full plus spectacles, she still had a 14 PD constant right esotropia and a 2 PD constant right hypotropia. Beginning treatment, the patient suppressed on Worth Dot testing and had no RDS stereoacuity, even with corrective prism in place. As her vision improved with amblyopia treatment, I continued to monitor her sensory fusion.

At the follow-up examination after nine weeks of patching and vision therapy for amblyopia, her visual acuities were equal in both eyes, and all testing showed normal correspondence. She was able to fuse on the Worth Dot test with 12 PDs base-out and 3 PDs base-up OD. With a trial frame, she was not able to appreciate RDS stereoacuity in-office. I prescribed 12 PDs base-out and 3 PDs vertical prism, split between her eyes.

At the follow-up examination, she reported no diplopia in her glasses, and, eventually, she was able to see 250 seconds of arc RDS stereoacuity. This patient continued with vision therapy to help improve her sensory and motor fusion with the hope of eventually titrating down the amount of prism she wears.

|

| Use the Fresnel prism trial set for patients with larger amounts of prism. |

Considering Options

Before settling on a final prism prescription, it is often helpful to trial frame the amount of prism you are about to prescribe to ensure that it will help you achieve your goals. Most trial lens sets come with prism lenses, but for larger angles of strabismus, it may be helpful to use a Fresnel prism trial set. Although younger patients may not be able to give good, subjective feedback, older children and adult patients should wear the trial prism set while engaging in an activity that normally causes them to experience diplopia or asthenopia (reading or distance viewing) to see if it eliminates diplopia and improves comfort.

Fresnel membrane prisms can be very useful for many aspects of prescribing prism. They are low in cost and can be easily applied to a pair of spectacle lenses in-office to try out on a patient for several days or weeks, and refining the prism prescription is inexpensive and simple. Fresnel prism, however, degrades visual acuity and contrast sensitivity, and some patients may not find it cosmetically appealing.12 A significant decrease in visual acuity through the Fresnel lens can be seen at larger prism powers, particularly at those greater than 12 PDs.13 When trialing Fresnel prism, it is advisable to only place the Fresnel over one eye so that the patient retains good binocular visual acuity with the prism in place.

Although cosmesis can be an issue with prism glasses, educating your patients on proper frame and lens selection will help them choose a frame and lens combination for the best cosmetic outcome. When prescribing ground-in prism, high index lenses, plastic frames and frames that are smaller in size help improve the weight and cosmesis of the lenses. Antireflective coating is also beneficial for patients wearing prism lenses.

Prism is a powerful tool that can be used to successfully treat a variety of binocular vision conditions. Prism prescriptions often greatly improve the quality of life of your patients by reducing asthenopia and diplopia. Although prescribing it can seem intimidating at first, with practice and a bit of trial and error, you can perfect your ability to prescribe prism for your patients in no time.

Dr. Jenewein is an assistant professor at Salus University, Salus University’s Principal Site Investigator for the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, a Fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and a Diplomate of the Binocular Vision, Perception and Pediatric Optometry Section of the Academy. Her research interests include strabismus and binocular vision disorders.

| 1. Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical management of binocular vision: heterophoric, accommodative, and eye movement disorders. 1994, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 632. 2. Jacobson DM. Divergence insufficiency revisited: natural history of idiopathic cases and neurologic associations. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(9):1237-41. 3. Godts D, Mathysen DG. Distance esotropia in the elderly. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(11):1415-9. 4. Tamhankar MA, Ying GS, Volpe NJ. Effectiveness of prisms in the management of diplopia in patients due to diverse etiologies. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49(4):222-8. 5. Tamhankar MA, Ying GS, Volpe NJ. Success of prisms in the management of diplopia due to fourth nerve palsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2011;31(3):206-9. 6. Neena R, Giridhar A. Effectiveness of prisms in relieving diplopia in superior oblique palsies. Kerala J Ophthalmol. 2016;28(1):38-42. 7. Caloroso E, Rouse MW. Clinical management of strabismus. 1993, Oxford, UK: Butterworth Heinemann Books. 8. Randomized clinical trial of treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(10):1336-49. 9. Scheiman M, Cotter S, Rouse M, et al. Randomised clinical trial of the effectiveness of base-in prism reading glasses versus placebo reading glasses for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(10):1318-23. 10. Teitelbaum B, Pang Y, Krall J. Effectiveness of base in prism for presbyopes with convergence insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86(2):153-6. 11. Pang Y, Teitelbaum B, Krall J. Factors associated with base-in prism treatment outcomes for convergence insufficiency in symptomatic presbyopes. Clin Exp Optom. 2012;95(2):192-7. 12. Cotter SA. Clinical uses of prism: a spectrum of applications. Mosby’s Optometric Problem Solving Series, ed. R. London. 1995, St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby. 13. Véronneau-Troutman S. Fresnel prisms and their effects on visual acuity and binocularity. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1978;76:610-53. |