|

A 77-year-old female patient presented to the office emergently with a chief complaint of pupil distortion. She was admitted to the hospital after a fall, had a small subconjunctival hemorrhage inferiorly. While looking at the eye more closely, she noticed her pupil looked funny. She explained she had not noticed this before and denied trauma to the eye. She had no previous medical or ocular history. She was taking only an oral antibiotic prescribed by her doctor and denied allergies of any kind.

Clinical Findings

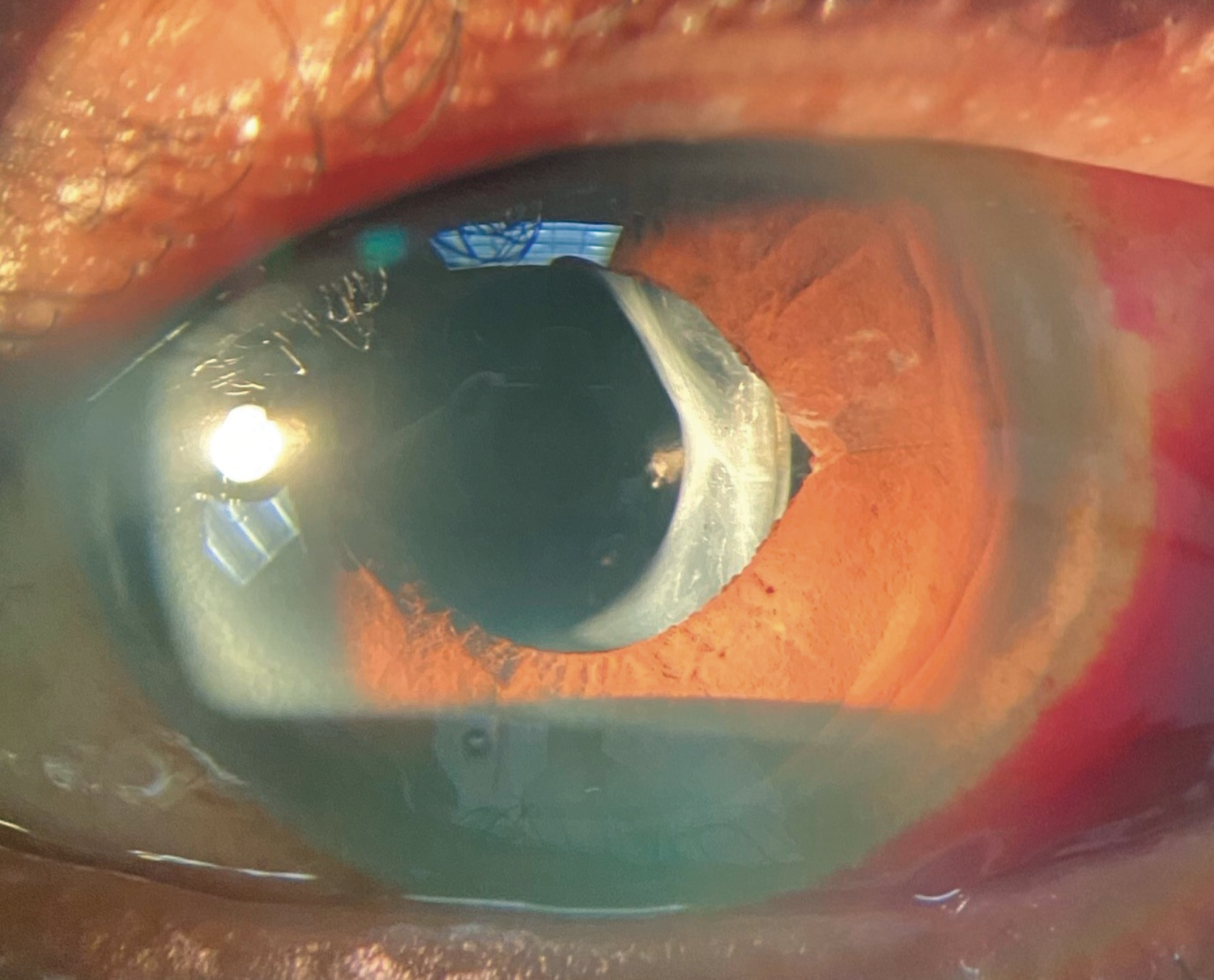

Her best-corrected entering visual acuities were 20/20 OD and 20/20 OS at distance and near. Her extraocular motilities were normal and her confrontation fields were full OU. The pertinent external and pupillary observations are demonstrated in the photograph. There was no afferent defect. Her biomicroscopic examination was normal and Goldmann applanation tonometry was measured at 17mm Hg in both eyes. Dilated fundus examination revealed no significant posterior pole or peripheral retina findings. The nerves were distinct with cup-to-disc ratios of 0.3/0.35 OD and OS.

Additional Testing

The clinician measured the pupils in both bright and dim illumination to rule out pathologic anisocoria. Inspecting old photographs was also completed to determine whether or not the issue was in fact new. The eye was dilated to confirm no posterior segment pathology.

|

|

This is the patient’s presentation. What does it tell you about the potential etiology? Click image to enlarge. |

Pathogenesis

The diagnosis in this month’s issue is vitreous prolapse inducing a peaked pupil. Cataract surgery has evolved and techniques have become less invasive and more precise with the advent of phacoemulsification; smaller corneal entry wounds result in less induced astigmatism and enable quicker visual recovery times.1 Self-sealing clear-corneal incisions are made with a keratome most frequently at the temporal limbus.2,3 The lens is then hydrodissected, phacoemulsified and the anterior chamber and capsule undergo irrigation and aspiration for removal of cortex and remaining viscoelastic prior to the placement of the intraocular lens implant. The corneal incisions are then hydrated and sealed with saline or a biocompatible surgical glue for efficacious closing of the wound; sometimes sutures are required.1

Complications following extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) include posterior capsular opacification, increased intraocular pressure, corneal decompensation, cystoid macular edema, retinal detachment and endophthalmitis. The intraoperative common denominator that increases the likelihood of these complications is posterior capsular rupture (PCR) with vitreous prolapse.4 The incidence of PCR is 0.2% to 14% with vitreous loss observed in 1% to 5% of cases.4-7

Additional risk factors for PCR include pseudoexfoliation (which creates zonular fragility), intraoperative miosis, high myopia and hypermature cataract.6,7 Zonular weakness and zonular dehiscence have been noted as a risk factor for vitreous prolapse without PCR in the setting of pseudoexfoliation syndrome, trauma and iatrogenic causes.8–10

The Perils of PCR

PCR must be recognized quickly, as continued phacoemulsification with a ruptured capsule can quickly worsen the tear. If any vitreous has prolapsed, triamcinolone acetate can be used to stain the vitreous so that the strands which require removal via anterior vitrectomy are more visible.5 Prolapsed vitreous has the potential to become connected to anterior segment structures, resulting in a peaked pupil, IOL decentration and incarceration of the vitreous into the surgical wound with wicking of external contents into the eye; this is referred to as wicking syndrome or a vitreous wick.5-10

Vitreous prolapse can occur even in the setting of what appears to be an intact capsule. Ruiz and Teeters reported 11 cases of vitreous prolapse following uneventful intracapsular cataract extraction, extending to the extraocular surface that occurred after a two-week postoperative period of otherwise sound corneal wounds.11 A small gelatinous mass was noted on the surface of the wound, which further peaked the pupil when tension was applied to it. Some patients exhibited wicking syndrome without any intraocular irritation, while others developed the clinical picture of endophthalmitis; creating an environment for severe vision loss.11 The authors hypothesize that the vitreous prolapse occurred secondary enlarged corneal incisions and tight corneal sutures.11

Rouw and Shaver reported two cases of uneventful ECCE that developed wicking syndrome.12 One case experienced PCR and vitreous prolapse into the anterior chamber seen on postoperative day one without any wound involvement. On postoperative day nine, the patient was noted to have a peaked pupil with a vitreous wick extruding through a corneal wound. A second case was reported after uneventful ECCE without PCR on 10-day follow up, where the patient presented with extremely elevated extraocular pressure, a mid-dilated pupil, iris bombé, vitreous prolapse with extrusion through the incisional wound. In both cases, the patients underwent anterior vitrectomy for removal of the retained vitreous.12

To avoid vitreous wicking syndrome, the surgeon must be considerate of risk factors that increase the possibility of PCR. While performing the capsulorhexis, if there is excessive movement of the lens or wrinkling of the anterior capsule, the procedure should proceed with caution as vitreous prolapse may occur in the absence of PCR.10

Should vitreous incarceration of the corneal wound occur, the vitreous wick can be pulled further exterior, excised with iris scissors and the remaining strand allowed to reenter the anterior chamber with an air bubble placed as a tamponade to keep the vitreous in place until the corneal wound is resealed. In the event of an inflammatory or infectious ocular reaction, high-dose topical steroid and/or antibiotic coverage may be administered with the patient closely followed.11

When incarcerated vitreous is excised, an anterior vitrectomy should be performed with topical antibiotic prescribed in the interim.12 If there is no clear extension of the vitreous extraocularly and the wound appears sound on the ocular surface, vitreolysis may be performed utilizing a Nd:YAG laser to sever the vitreous strand. This may relieve the induced corectopia.13

Dr. Gurwood thanks Dr. Colin Kane for his contributions to this case.

Dr. Gurwood is a professor of clinical sciences at The Eye Institute of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University. He is a co-chief of Primary Care Suite 3. He is attending medical staff in the department of ophthalmology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. He has no financial interests to disclose.

|

1. al Mahmood AM, Al-Swailem SA, Behrens A. Clear corneal incision in cataract surgery. Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology. 2014;21(1):25-31. 2. Ong-Tone L, Bell A. Practice patterns of Canadian Ophthalmological Society members in cataract surgery - 2009 Survey. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2010;45(2):121-124. 3. Greenberg PB, Havnaer A, Oetting TA, Garcia-Ferrer FJ. Cataract surgery practice patterns in the United States Veterans Health Administration. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 2012;38(4):705-709. 4. Chan E, Mahroo OAR, Spalton DJ. Complications of cataract surgery. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2010;93(6):379-389. 5. Chakrabarti A, Nazm N. Posterior capsular rent: Prevention and management. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017;65(12):1359-1369. 6. Zare M, Javadi M-A, Einollahi B, Baradaran-Rafii A-R, Feizi S, Kiavash V. Risk Factors for Posterior Capsule Rupture and Vitreous Loss during Phacoemulsification. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2009;4(4):208-212. 7. Vajpayee RB, Sharma N, Dada T, Gupta V, Kumar A, Dada VK. Management of posterior capsule tears. Survey of ophthalmology. 2001;45(6):473-488. doi:10.1016/S0039-6257(01)00195-3. 8. Tabatabaei SA, Rajabi MB, Tabatabaei SM, Soleimani M, Rahimi F, Yaseri M. Early versus late traumatic cataract surgery and intraocular lens implantation. Eye (Basingstoke). 2017;31(8):1199-1204. 9. Ritch R, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U. Exfoliation syndrome. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2001;45(4):265-315. 10. Sangal N, Chen TC. Cataract surgery in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Seminars in Ophthalmology. 2014;29(5-6):403-408. 11. Ruiz RS, Teeters VW. The vitreous wick syndrome. A late complication following cataract extraction. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1970;70(4):483-490. 12. Rouw J, Shaver JF. Vitreous wicking syndrome as a complication of extracapsular cataract extraction. Optometry. 2008;79(4):193-196. 13. Levy JH, Pisacano AM. Clinical experience with Nd:YAG laser vitreolysis in the anterior segment. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 1987;13(5):548-550. |