(Editor's note: This version reflects recent changes in legislative activity that took place after the print edition went to press. Since scope laws and efforts are constantly evolving, you can always find timely updates on our online News Feed.)

Twenty-six years ago this month, Oklahoma ODs earned the right to perform minor laser surgeries, the first such law in the nation. In time, 10 other states followed with laser laws of their own—six of those within the last five years alone, the most recent of which occurred just weeks ago. Eight more states have laser bills active currently, setting up a contentious year for optometry as advocates and opponents vie for the favor of elected officials. Clearly, the pace of change is quickening.

Laser laws get the most attention—and, from detractors, condemnation—but optometry has been racking up wins all across the board in practice scope, be it lid lesion removal or collagen crosslinking or controlled substance prescribing. For decades, optometric advocates have been fighting legal battles to modernize the profession’s practice scope, which, in many states, comprises the same language it did in the ’90s. Not only have eyecare treatments and technology evolved dramatically during this time, but training and education curricula have intensified, the population has aged and the ophthalmology workforce has declined, putting optometrists in a prime position to meet the nation’s growing eyecare demands and improve patient access to necessary care.

“The more well-educated and well-qualified providers there are who can provide a service—like a laser procedure, an injection or an eyelid lesion removal—the sooner patients can get the care they need, and that’s the biggest reason why scope expansion is so important,” says Nate Lighthizer, OD, associate dean at NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry and one of the foremost educators on advanced procedures in optometry.

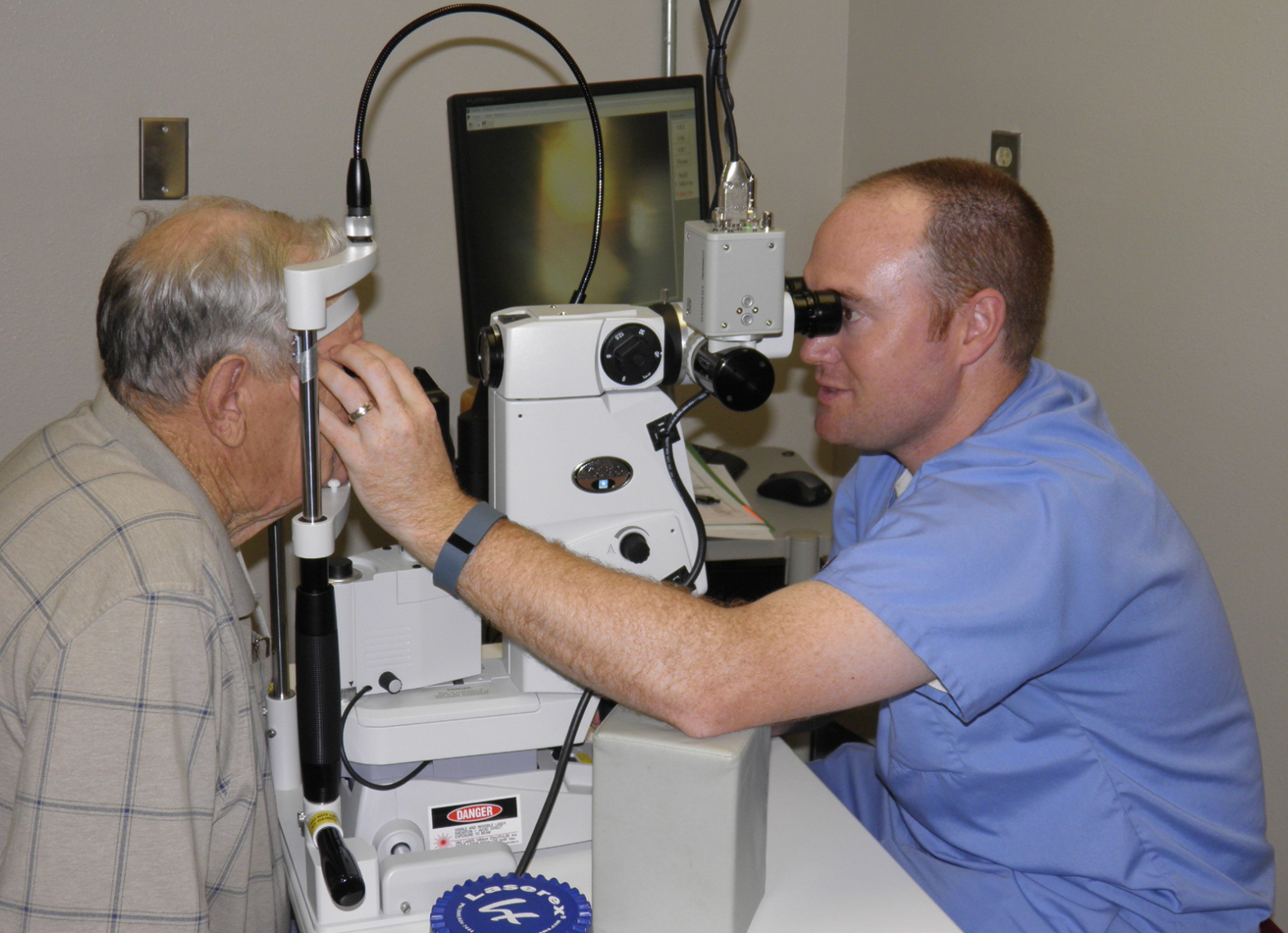

|

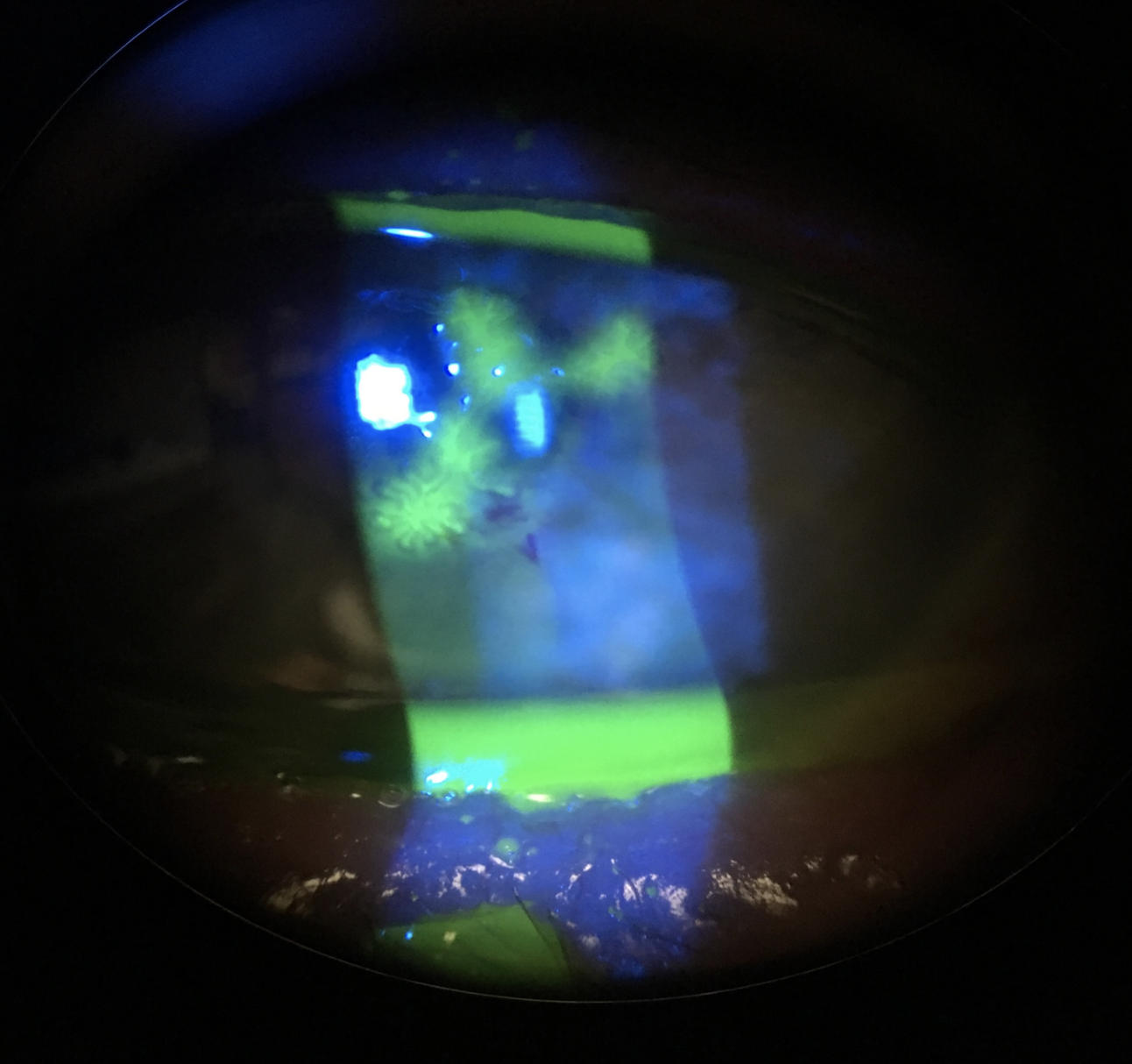

| Dr. Lighthizer—a leading educator on advanced optometric procedures—performing YAG capsulotomy on a patient. Photo: Nate Lighthizer, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Educational institutions have admirably evolved their curricula to meet current and future eyecare needs. Today’s optometry students are being taught to perform minor surgical procedures, such as lesion removal, subcutaneous injection and laser procedures including selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT), YAG capsulotomy and laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI). Trouble is, newly minted optometrists too often find their capabilities throttled by regressive optometry laws and an inhospitable or just plain clueless medical community that doesn’t know how to integrate optometry into the broader healthcare system.

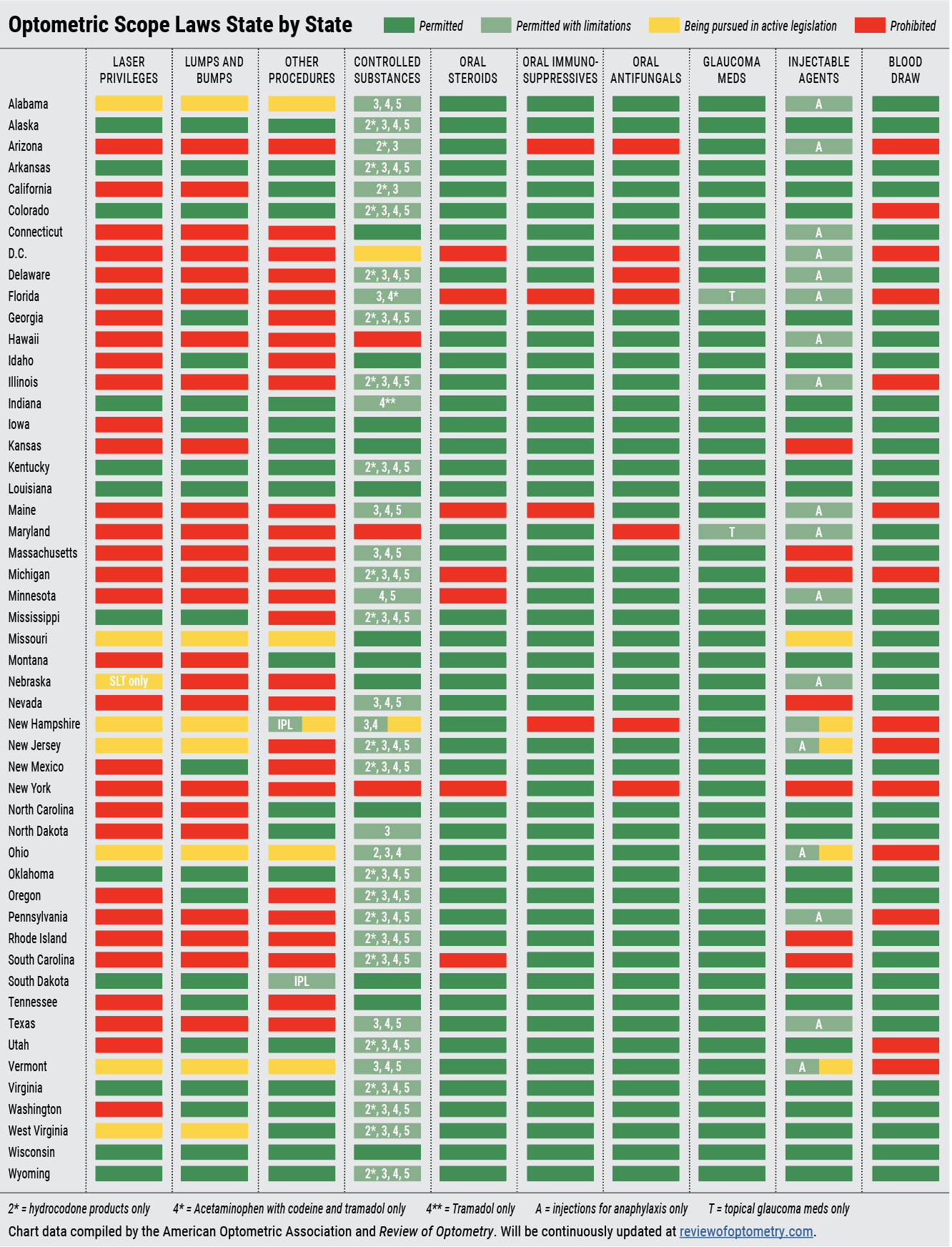

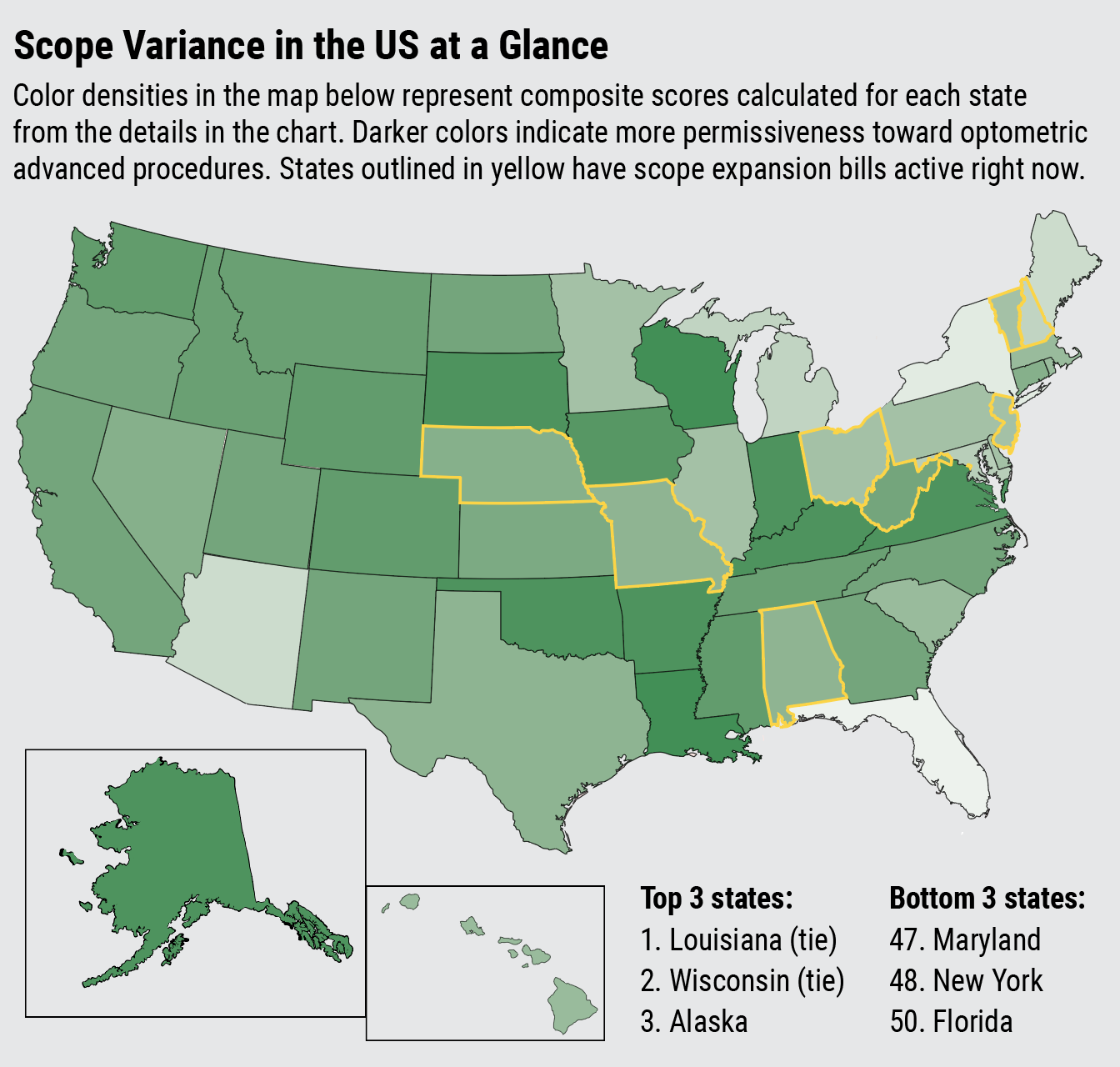

Scope expansion is by its very nature fragmented—rules are set at the state, not federal level—perhaps masking the extent of evolution now taking place. In the first portion of this article, we’ll discuss scope expansion wins that various states have secured over the last five years, followed by a state-by-state breakdown of current legislative efforts in play. Afterwards, we’ll explore which optometric privileges are on the rise and how to implement these new services into your practice once your state allows it.

Trends and Challenges

Since 2019, more than 20 scope expansion bills have been introduced. While not all were successful, these efforts granted additional privileges to optometrists in at least 14 states, six of which passed laws that include the use of lasers.

Not every state must return to the legislature to authorize new procedures, however; one such exception is Wisconsin, where an increasing number of ODs are embracing expanded practice rights under a scope law that’s been untouched since 1990, but due to its specific phrasing, ODs there are able to implement new procedures and therapeutic agents at their own discretion, thus quietly bringing the number of laser states up to 11 (for more, read this news story). Now, seemingly in the blink of an eye, the tally of optometric laser states has risen to 12 following the passage of South Dakota's scope expansion bill earlier this month.

Take a look at this brief timeline of some legislative wins in optometry just since 2019:

- South Dakota (lasers, March 2024)

- South Dakota (intense pulsed light, October 2023)

- New Hampshire (vaccine authority for influenza, COVID-19 and shingles, August 2023)

- Washington (non-laser advanced procedures, May 2023)

- Colorado (lasers, June 2022)

- New Hampshire (expanded glaucoma treatment authority to include all glaucoma types, May 2022)

- Virginia (lasers, March 2022)

- California (intense pulsed light and foreign body removal, October 2021)

- New York (topical/oral meds, October 2021)

- Texas (oral medications, June 2021)

- Wyoming (lasers, April 2021)

- Mississippi (lasers, March 2021)

- Massachusetts (topical/oral meds, January 2021)

- Iowa (non-laser advanced procedures, June 2020; in April 2023, the law was clarified to authorize anesthesia injections for lid lesion removal)

- Arkansas (lasers, March 2019)

At a glance, it may seem like the scope expansion wave has decelerated, given that 2023 was the first year in the last five in which no states were granted laser authority despite attempts in Alabama, South Dakota and Idaho, and following the high-profile veto of California’s bill in 2022. In actuality, enthusiasm and advocacy for scope expansion is at an all-time high, with more states actively pushing for laser rights in 2024 than in any previous year. Not to mention that South Dakota has already started the year off strong by becoming the 12th laser state on March 4.

Standing in the way of these efforts time and again are ophthalmologists and organized medicine, which consistently present to legislators the same spurious claim that optometrists are not properly trained to perform surgical procedures. Governor Newsom of California cited this reasoning when he vetoed the state’s first laser bill attempt in 2022, though his letter defending his decision included inaccuracies regarding the number of years optometrists undergo training.

“This is the only argument that ophthalmology has been able to claim, and it’s never come to fruition, but that’s what they cling to in every scope battle that comes along,” says Angelique Sawyer, OD, legislative co-chair of the New Hampshire Optometric Association, which is currently pushing to authorize lasers and advanced procedures. “We’re not asking for things that are outside of our training and education, and we’ve proven time and time again that when the legislature grants us authority and increased scope, we do it responsibly and to the benefit of our patients,” she says.

Dr. Lighthizer reiterates that “optometrists have a great track record of safely performing these procedures,” but adds that there will always be political opposition. “I think the reason why some states struggle is because you have to have the right people in place to pass a law,” he notes. For example, scope advocates in states with legislators who are also medical doctors—such as West Virginia and California—may have a more difficult time hammering home the safety and necessity of OD-performed procedures.

As optometric scope expansion becomes embraced in more states, evidence to validate the inclusion of these procedures in optometry’s skillset will continue to mount. Next, we’ll discuss the status of various scope efforts in pursuit across the nation.

The State of the States

This year is bound to be a disruptive one for scope expansion, with nine remaining active bills in pursuit literally all over the map, including in Alabama, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Missouri, Ohio, Vermont, Washington D.C. and West Virginia. South Dakota has already claimed the first legislative win of 2024 on March 4 when ODs there gained the authority to perform laser and advanced procedures. Other states haven't been so fortunate, including California, Kansas and Utah, whose laser bills have already flamed out for this year. Nonetheless, the aforementioned others remain live issues. Let’s survey the status of current efforts.

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Alabama. After getting stonewalled in 2023, Alabama ODs and advocates are prepped to pursue a second battle this year. Last year’s bill, HB 249, which proposed certain laser and advanced procedures, passed the House only to be terminated weeks later by the Senate Healthcare Committee, which refused to bring it to the floor for a vote. This year, Alabama plans to introduce a similar bill, the details of which are still being hashed out at the time of this writing.

|

|

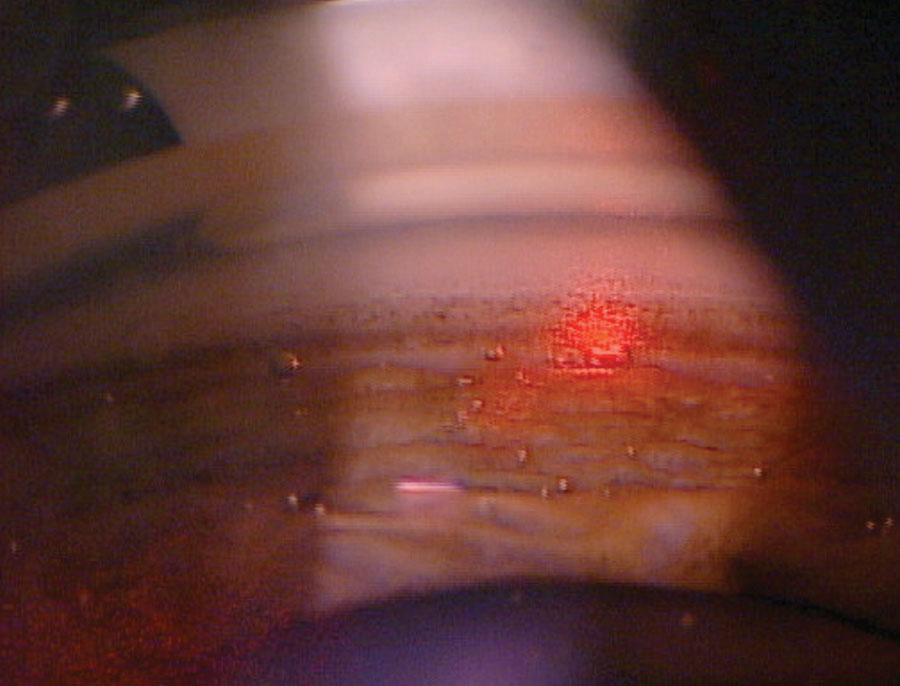

ODs in 12 states—and counting—can now perform SLT, an increasingly common first-line treatment for glaucoma. Photo: Nate Lighthizer, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Nebraska. This state’s scope bill, LB 216, currently remains in the Health and Human Services Committee, where it’s been residing since last January without any movement, though the state’s optometric association is optimistic that it will be voted out soon.

Nebraska’s bill differs from others by proposing to add only one laser procedure to optometry’s practice scope: SLT, which is growing in acceptance as a first-line option to treat glaucoma. Considering how aggressive the opposition has proven to be in other states’ recent laser battles, the Nebraska Optometric Association says that focusing their efforts initially on advocating SLT will give the state a solid starting point for future scope expansion endeavors.

New Hampshire. This state made two changes to its practice scope in the last few years, in 2022 gaining the right to treat all types of glaucoma (rather than only POAG) and the following year winning authority to administer adult vaccines for influenza, COVID-19 and shingles. Hoping to keep this momentum going, local ODs are now pursuing YAG capsulotomy, SLT and other minor surgical procedures that fall within the profession’s education.

So far this year, SB 400 is moving quicker than similar legislation in other states, having passed the Senate in early February and now awaiting a committee assignment in the House. Dr. Angelique Sawyer of the New Hampshire Optometric Association explains that while this is a scope bill, it’s also a regulatory bill that would give more authority to New Hampshire’s optometry board to determine training and certification requirements, something that several other states are also advocating for.

“If this bill goes through as is, the board will have more ability to approve certain things as new training and technology comes along without having to go back for legislation every time,” she explains.

While improved access to care is a leading argument for expanding optometry’s scope, this is especially true in more rural states like New Hampshire. “For six out of 10 counties in New Hampshire, access is a very significant issue,” Dr. Sawyer points out. “There are just not enough providers to go around, and it’s going to get worse. So, for the benefit of patients, every state needs to be able to get to this point where patients have more access to the full complement of what optometry has to offer,” she stresses.

New Jersey. Like Nebraska, this state is currently pursuing laser legislation that was introduced last year during a two-year legislative session. The identical bills, A-920 and S-354, have not moved yet in 2024 and are awaiting hearings in their respective branches of government. The bills propose adding several practice privileges for New Jersey ODs, including three laser procedures—SLT, capsulotomy and LPI—removal of styes and skin tags and an expansion of vaccine and prescription authority. As New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the US, allowing its optometrists to offer these services would have a profound impact on access to care.

“By expanding the scope of practice, optometrists can provide critical eye care when and where it’s needed most and ensure all New Jersey residents have timely access to vision and medical eye care,” says Keira Boertzel-Smith, executive director of the New Jersey Society of Optometric Physicians. “It also lowers costs by eliminating duplication of services and extra co-pays for redundant office visits and reduces patient travel time and missed hours at work,” she adds.

Despite the opposition’s claims that New Jersey ODs lack adequate training to perform these procedures, the state has one of the most rigorous continuing education requisites in the country, requiring ODs to complete 50 hours of CE every two years to retain their licensure. With continued advocacy, legislators will hopefully recognize the illegitimacy of these claims.

Missouri. Two identical laser bills are in the running here this year, SB 956 and HB 1963, which propose the expansion of optometry’s practice scope to encompass all procedures taught in optometry schools today, including minor surgery and the use of lasers. SB 956 is still awaiting an initial hearing in the Senate, while HB 1963 completed a public hearing in the house on February 13, the verdict of which had not yet been finalized at the time of this writing.

Ohio. The last update to optometry’s practice scope in Ohio dates back to 2007, highlighting the need to modernize the law to reflect the many changes in technology and training that have occurred since that time. That’s the goal of SB 129, a two-year bill introduced last June that proposes allowing Ohio ODs to remove benign lesions, cysts and skin tags, as well as use lasers for YAG capsulotomy, SLT and LPI. It also seeks to update ODs’ pharmaceutical authority to permit the treatment of any eye condition and epinephrine injection. Additionally, like many other states pushing for expanded practice rights, the bill advocates increasing authority of the Vision Professionals Board to establish training guidelines.

The bill hasn’t seen any movement yet this year, but a hearing was scheduled in the Senate Health Committee for February 28. During this waiting period, Lindsay Florkey, OD, president of the Ohio Optometric Association, says, “OOA members have been actively meeting with the members of the Senate Health Committee in their respective legislative districts, continuing to educate them about how our members are their constituents’ primary eye doctors and the importance of SB 129 in allowing ODs to provide enhanced vision services based on our proven comprehensive training and education.”

South Dakota. Last year saw both highs and lows for scope expansion advocates in this state. While South Dakota ODs celebrated gaining the authority to perform intense pulsed light treatment (IPL) due to a change in regulations last fall, this right was immediately challenged the state medical association, which even issued a lawsuit to reverse the changes. Also in 2023, ODs in the state mourned the loss of their laser bill, which was shot down by the House Health and Human Services Committee.

This year, the state has met a more fortunate fate; just a few weeks ago, South Dakota secured the first scope win of the year when Governor Kristi Noem signed the state’s laser bill into law. The bill also resolves the dispute over the use of IPL by clearing up the pending lawsuits.

“Despite all of these procedures being taught in every optometric college in the nation since at least 2015, optometrists are required to complete a three-part ‘prove up’ process to perform any added procedure,” the South Dakota Optometric Society wrote in a recent statement. The “prove up” process included in the bill requires:

- Passage of a national examination on laser procedures and a national examination on injection procedures (graduates prior to July 1, 2024 are grandfathered in).

- Passage of a 32-hour certification course to demonstrate competency on each of the added procedures.

- Hands-on demonstration of the procedures on at least five human eyes for eyelid procedures and SLT and 10 human eyes for YAG under the direct supervision of an ophthalmologist or authorized optometrist to prove competency in each of the procedures.

In the statement, SDOS president-elect, Ashley Crabtree, OD, said, “I am so proud of our member doctors for the support they provided in passing this bill. When asked, they responded and met with legislators, texted, called and emailed... We also had a robust social media and digital ad campaign to support the effort.” (For more on South Dakota's laser bill, read this news story).

Vermont. The failure of a 2020 attempt to add in-office procedures (e.g., injections, lesion removal and certain lasers) to this state’s scope of practice was attributed to a negative report from the state’s Office of Professional Regulation (OPR), which cited concerns over education and training. But last September, the OPR communicated its newfound support for the expansion of optometry’s practice scope to include various in-office procedures. The reason for the change of heart: optometry’s persistent advocacy. After receiving pushback from ODs and the Vermont Optometric Association, the state Assembly tasked the OPR with reinvestigating the matter, this time including more data on advanced procedure training and education curriculums in US optometry schools.

Armed with this new positive report from the OPR, Vermont is pursuing another laser bill (S.233) in the state’s 2024 legislative session. It currently awaits a hearing in the state’s Senate Healthcare Committee, which is expected to take place soon.

Washington D.C. While not pursuing laser privileges, this jurisdiction is looking to modernize the scope of practice for numerous allied health professionals, including optometrists. Bill 25-0545 seeks to allow ODs in D.C. to prescribe and administer controlled substances for ocular conditions, which is currently authorized nearly everywhere else in the country (except for in Hawaii, Maryland and New York). A hearing to discuss this bill was held this past December, and no further actions have been filed since.

West Virginia. A laser bill introduced here last January cleared the House but was ultimately killed in the Senate. This year, however, West Virginia ODs rebounded from the loss and have reintroduced an identical bill, HB 4783, which proposes the modernization of the practice scope to encompass all procedures taught in optometry schools today. This includes minor and surgical procedures such as lesion removal, capsulotomy, SLT and LPI.

In late January, HB 4783 passed the House Health Committee and now heads to the state’s Senate Health and Human Services for consideration. Since this is where the bill’s progress came to a halt last year, the West Virginia Optometric Association and other advocates are preparing for the battle ahead.

“As most states, we have legislators with opposing opinions of what the changes will actually do,” explains Chad Robinson, the association’s executive director. “We also have two state Senators who are medical doctors in their day jobs, so this is definitely one of the challenges. Others include the scare tactics and misinformation that will continue to be spread by the opposition.”

The last change to West Virginia’s practice scope was in 2010, when ODs there gained the authority to perform minor surgical procedures (foreign body removal, punctal plugs and lash epilation), epinephrine injections and expanded pharmaceutical privileges.

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Integrating New Services

With nearly 12 states currently lobbying for scope expansion of some sort in 2024 and more planning to in the future, thousands of optometrists will likely soon find themselves asking, “How do I implement these new services into my practice?” To help prepare you for when this time comes, below several seasoned ODs share their best practices and advice on adding various privileges, including lesion removal, injections, oral medications and laser procedures.

Incisions and injections. Two practice privileges being increasingly embraced as responsibilities of optometry’s profession include intralesional injections and minor in-office procedures such as removal of lesions in and around the eye. The recent passage of South Dakota's scope bill brings the total count of states where ODs have injectable authority to 42, though 17 of these only permit injections to treat anaphylaxis. Additionally, optometrists in 20 states can now remove lumps and bumps.

The first step of implementing these procedures is to equip your office with the right tools for the job. To accommodate more clinical uses, it helps to have a wide variety of different sizes and types of syringes, needles, clamps, scalpels and blades, many of which can be purchased at once as part of a surgical instrument kit. You’ll also need forceps, gauze pads, a high-temperature cautery, eye patches, a sharps container and several other items. For a full shopping list of materials you may need, see Equipping Your Office for Minor Surgical Procedures from our December 2023 issue.

One thing to be vigilant about for the safety of you, your patients and your staff is proper sanitation of tools and equipment before and after each procedure, as well as the use of PPE. Corri Collins, OD, who practices in Kentucky, says that before removing a lesion, for example, she first creates a sterile environment and positions the necessary equipment nearby (a sterile betadine swab, sterile gloves and erythromycin ointment).

Remember that the standard of care in all 50 states is that lesions with risk of malignancy be tentatively diagnosed as cancerous and biopsied, and most states legally prohibit ODs from removing a cancerous growth. Therefore, if there is any doubt a lesion could be malignant, referral to an ophthalmologist for excision and biopsy is warranted.

Lastly, ensure you and your staff have defined a plan of action to handle emergencies or adverse events that arise when patients are under the needle or scalpel.

Confidence performing these procedures comes with experience, but several resources are available for optometrists who wish to brush up their knowledge and skills for performing incisions and injections. Most importantly, take advantage of courses and training sessions held by your state’s optometric association or optometry board. It can also be valuable to pick the brains of colleagues from other states who have years of experience performing these procedures. For reading material, The Atlas of Primary Eyecare Procedures can be a useful resource to keep on-hand at your practice.

Oral medications. Patients in all 50 states can now prescribe some form of oral medication, such as antivirals, antibiotics, antifungals, anti-inflammatories, analgesics, antihistamines and steroids. Here’s a breakdown of the states that allow ODs to prescribe some of these specific drugs:

- Controlled substances: 47 (exclusions: Hawaii, Maryland, New York, D.C.)

- Oral glaucoma meds: 48 (exclusions: Florida, Maryland)

- Oral immunosuppressives: 46 (exclusions: Arizona, Florida, New Hampshire, Maine)

- Oral antifungals: 44 (exclusions: Arizona, Delaware, Florida, New Hampshire, Maryland, New York, D.C.)

- Oral steroids: 44 (exclusions: Florida, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, South Carolina, D.C.)

- Hydrocodone: 36

Taking advantage of expanded pharmaceutical privileges in your state gives you the opportunity to provide your patients with more comprehensive care. Additionally, prescribing oral meds in-house can help reduce referrals to ophthalmology.

A Refresher on Controlled Substances in Eye CareHere’s a quick review of which types of drugs, substances and chemicals make up each schedule and some examples in each category, though not all will be used in eye care. (Note: There are no Schedule I drugs used in eye care, hence its exclusion from this list). Schedule II: This schedule of drugs—the second-most dangerous—is characterized by agents with a high potential for abuse and the possibility of use leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. Some examples include morphine, oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), hydromorphone (Dilaudid) and combination products with less than 15mg of hydrocodone per dosage unit. Schedule III: These drugs have a moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Some examples include products containing less than 90mg of codeine per dosage unit (Tylenol with codeine), ketamine and anabolic steroids. Schedule IV: Drugs in this category have a low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence. A few examples include alprazolam (Xanax), carisoprodol (Soma), lorazepam (Ativan), midazolam (Versed), tramadol (Conzip, Ultram), pentazocine (Talwin) and zolpidem (Ambien). Schedule V: Schedule V drugs have even lower potential for abuse than those in Schedule IV. Many of these are anti-anxiety medications, sleep agents, antidiarrheals or analgesics. Some examples include pregabalin (Lyrica), cough medicine with less than 200mg of codeine or per 100ml (Robitussin AC) and diphenoxylate-atropine (Lomotil). |

“Many common ocular and periocular conditions and their sequelae are treated with oral medications,” says Jill Autry, OD, RPh, who practices in Texas, which passed a law in 2021 allowing ODs to prescribe oral meds. “It is important for optometrists to be able to use these options, as most patients have easier access to an OD when an ocular condition arises. This is because there are many more optometrists than ophthalmologists, optometry offices are often open later and often on Saturdays and most patients have an established relationship and medical/ocular history with an optometrist,” she explains.

|

|

A cornea presenting with herpes simplex dendritic keratitis. Dr. Autry notes that oral antivirals typically outperform topical treatments in cases of herpetic disease. Photo: Jill Autry, OD, RPh. Click image to enlarge. |

Prescribing a wider range of oral medications as your state allows it can essentially help you morph from a primary to a secondary care provider, which is increasingly needed in optometry given the progressive decline in the ophthalmology workforce and the aging population, Dr. Autry argues. “A large portion of the US is uninsured or underinsured, and optometry tends to be a more cost-effective option for patient care,” she adds.

If learning the ins and outs of prescribing oral medications seems daunting at first, Dr. Autry points out that it’s important to remember that these drugs are routinely used by several other medical personnel, including general and nurse practitioners and physician’s assistants. “They use the same meds over and over that they are comfortable prescribing as they learn the pros and cons, dosages and side effects of each, as well as the rare pitfalls that may occur,” she notes.

When preparing to offer oral meds at your practice, the first step is becoming familiar with your state’s laws and requirements. Some oral medications may not have restrictions, while others, such as oral steroids, may have defined limits on the number of pills or length of therapy. You can always contact your state’s optometric association with questions on the logistics of prescribing.

When you’re ready and able to adopt this service, Dr. Autry shares some general advice to consider in the prescribing of various oral meds:

Antivirals: These drugs are typically well-tolerated with rare prescribing issues and have fewer side effects than topical trifluridine. Current research suggests that oral antivirals should be used over topical treatments for herpetic disease.

|

|

This severe preseptal cellulitis due to MRSA should be treated promptly with oral antibiotics. Photo: Jill Autry, OD, RPh. Click image to enlarge. |

Antibiotics: While these are usually well tolerated, be sure to check allergies first. Oral antibiotics are mostly used for periorbital skin infections, so prescribe these in addition to hot compresses and watch out for poor response. If there’s no improvement in 72 hours, consider a change in antibiotic and take note of MRSA signs, symptoms and risk factors.

Antifungals: The application of these drugs in primary eyecare is limited; however, antifungals can be used along with topical antifungal treatment for fungal keratitis. If there is any suspicion of a fungal infection, these cases must be referred or at least heavily comanaged with an ophthalmologist or cornea specialist.

Anti-inflammatories: By and large, optometrists use OTC ibuprofen and not Rx NSAIDs, though these may be combined with topical steroids for systemic treatment of uveitis or with acetaminophen OTC for analgesia.

Antihistamines: These drugs can be prescribed OTC for systemic aid to topical allergic treatments. They’re typically safe and well tolerated, aside from the potential of somnolence and eye dryness.

Oral steroids: These have great potential in treating certain ocular conditions but also the biggest potential for severe side effects that vary based on age, systemic conditions, other medications, etc.

It is critical to read up on the potential adverse effects, treatment protocols and contraindications of the different oral medications to improve patient selection and avoid negative outcomes.

Dr. Autry also recommends having a “go-to” medication for each condition you treat at your practice. “Make a chart for the dosages and length of therapy normally used to make it easier and faster when first learning to prescribe,” she suggests. “Add a column for special population concerns—such as allergies, pregnancy, kidney or liver dysfunction, diabetes and so on—so you are triggered to ask the right questions and consider medication or dosage changes.”

Once you put in the work in preparing your practice to prescribe oral meds, Dr. Autry assures, “It’s not that hard, and you get comfortable very fast.”

Laser procedures. The use of lasers by an optometrist for glaucoma treatment and post-cataract care is permitted in fewer states—12—than any other optometric privilege, though every year more states are lobbying to have it included in their practice scopes. With 10 more pursuing lasers this year alone, and one that already succeeded, there is likely an impending surge in the number of optometrists who can perform procedures such as SLT and YAG capsulotomy.

While this high-profile responsibility may feel intimidating to integrate into your practice at first, there are many ways to set up for success when your state adds lasers to its scope. Implementation involves ensuring you have the proper training based on your state’s law, purchasing or accessing equipment and determining how to fit the procedures into your practice schedule.

“You first have to decide what kind of laser to purchase: a YAG, an SLT laser or a combination system,” says Dr. Lighthizer, a longtime laser-use advocate and educator. He notes that his personal choice is a combination laser since it can perform both capsulotomy and SLT.

Rather than purchasing a laser, another option is to lease or share one with a colleague. To determine the best route, as well as the type of laser to acquire, consider how frequently your practice refers patients out for each procedure and what the return on investment will be.

One plus that Dr. Lighthizer points out is that since a laser can double as a slit lamp, it doesn’t have to take up additional space. “You could set this up in one of the exam rooms, and when it’s not being used as a laser, you could also examine patient’s eyes with it,” he says.

Capsulotomies probably represent the bigger optometric opportunity, simply because of the higher volume of cataract surgeries performed each year vs. the size of the glaucoma population. Still, SLT is becoming a mainstream first-line glaucoma treatment and its importance to optometry practices will only continue to grow.

When you’re getting comfortable performing procedures like SLT, YAG capsulotomy and LPI, it’s worthwhile to reach out to ODs in states with longstanding laser laws. Attending trade shows and meetings with your state’s optometric association also allows you to get hands-on experience and ask questions.

Finally, when fitting laser procedures into the workflow, Dr. Lighthizer likes to designate chunks of time on the schedule for laser and surgical procedures. That way, he can direct his focus on that for an entire morning or afternoon without having to juggle things like general exams and dry eye evaluations in between.

Circling Back to Scope Success StoriesWe touched based with two laser states—Alaska (2017) and Colorado (2022)—to see how things have been going since the scope expansion. Speaking on Alaska’s experience is Paul M. Barney, OD, president of the Alaska Optometric Association and on the Board of Trustees at the AOA. From Colorado, answers were provided by past presidents of the Colorado Optometric Association and Fellows of the AAO, Deanna Alexander, OD and Jon Pederson, OD. How has expanding the practice scope affected patient care and access in your state? Alaska: In a state that has a limited road system and where optometric care is the only eye care in many rural areas of the state, our expanded scope has reduced travel costs to patients, who prior to our scope expansion, often had to fly to other areas of the state to access care. Colorado: It has allowed patients to receive the care they need through the doctors they trust and have established relationships with. Enabling doctors to provide the care they are trained to perform increases access and decreases duplication of services. Over 200 doctors have gone through the certification process outlined in our law and specified by our state board. The COA has worked hard to help doctors integrate these procedures into their offices. Did you experience any major setbacks during the legislative process? Alaska: We ran our first scope expansion bill including laser privileges in 2015, which passed the Senate and House committees, but it needed a passing House floor vote to be sent to the Governor for signature. Before our bill could be heard, the session ended, and we had to start over with a new bill in the next session. Through that heartbreaking defeat, we learned a valuable lesson; had we been more effective in educating the leadership, our bill would have been placed higher in the queue and would likely have gotten a floor vote. Colorado: We ended up having additional hearings in more committees than we anticipated, many of which differed from those that typical healthcare bills move through; however, we overcame this with our incredibly strong grassroots. Our doctors had relationships with members of all these committees. Establishing these relationships was a multi-year process. How did you deal with pushback from the opposition? Alaska: The ALOA is a small organization with limited resources, so it was difficult combatting the attack ads and rhetoric put out by those opposed to our bill. Despite this, many of our members were engaged and well-connected to their legislators, which helped us send them an accurate and reasoned message untainted by the fear tactics used in many of the attack ads. Colorado: Ultimately, legislators realized that we were capable of performing these procedures. Data from other states demonstrated a strong safety profile, and there was a need to increase access to care throughout Colorado. The opposition could not overcome those points. What role did advocacy play in the bill’s success? Alaska: Without advocacy and legislator relationships, our scope bill would not have passed. We wouldn’t have been able to accurately explain to legislators the access to care issues that Alaskans faced, the level of education and training optometrists receive or that by not expanding scope of practice, Alaska was underutilizing the potential that optometry brings to our healthcare system. Colorado: Advocacy is paramount to the bill’s success. Legislators make decisions about so many issues; it is our job to be a resource to educate legislators about our profession, training and businesses. This cannot be done in the middle of a bill; the groundwork needs to be done years in advance. |

Takeaways

It’s only a matter of time before the use of optometric lasers and procedures such as lesion removal are mainstream across the profession. If your state is among those currently pursuing expanded practice rights, remember to support and reach out to your optometric association to learn how you can aid in advocacy efforts. If you already practice in a state with a broad scope, consider taking advantage of these opportunities to provide your patients with more comprehensive, timely and accessible care.