|

A 44-year-old woman presented to the office with a chief complaint of “a quivering left upper eyelid,” of two weeks’ duration. She said the issue has gradually become worse, making her self-conscious. She did not report any pain. She denied trauma, systemic disease and allergies of any kind.

Clinical Findings

This patient’s best-corrected entering visual acuities were 20/20 OD and 20/20 OS at distance and near. Her external examination was unremarkable, with no evidence of afferent pupillary defect.

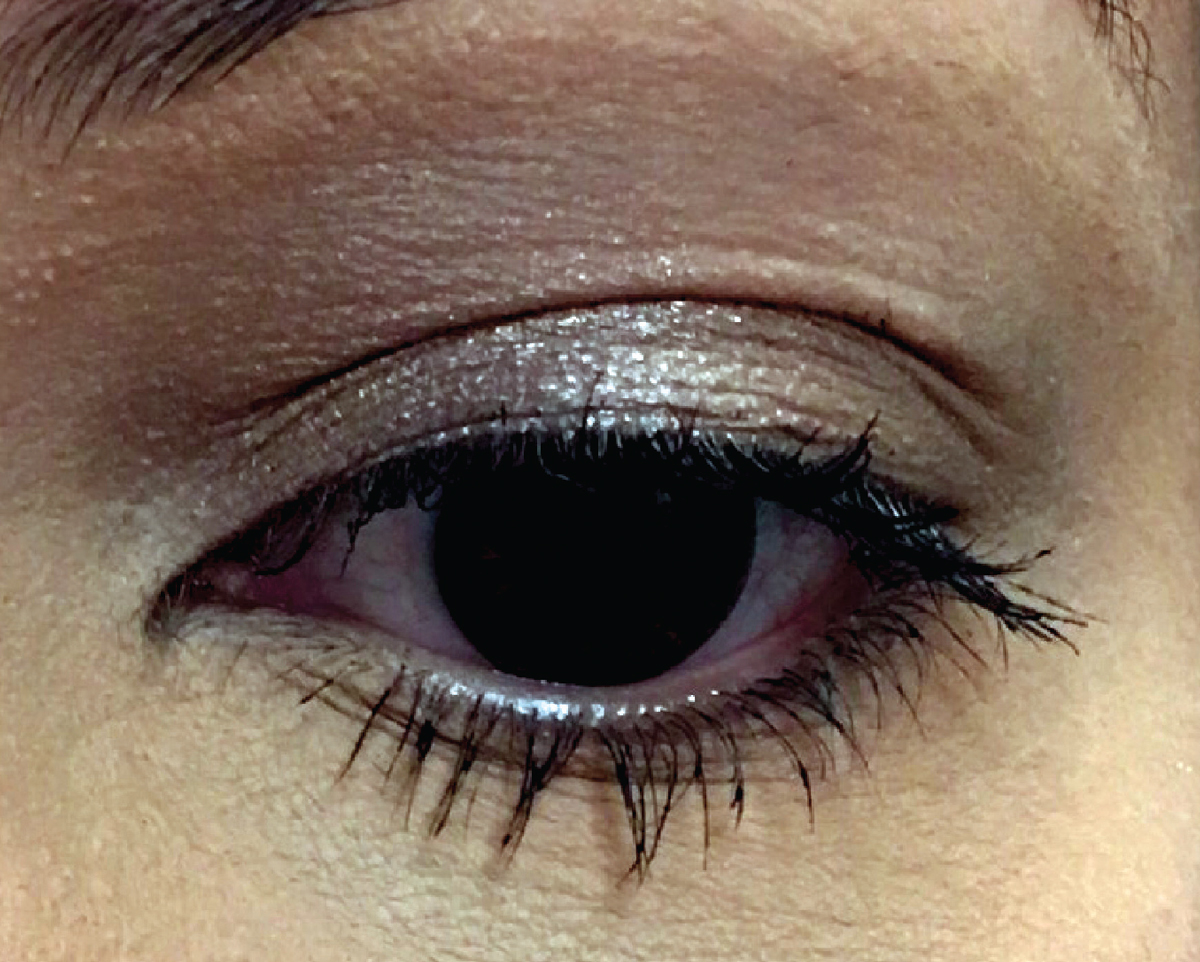

A normal appearing left lid is demonstrated in the photograph; however, in an exam setting it can be observed to episodically and randomly quiver. Her anterior segment findings were normal and Goldmann applanation tonometry measured 17mm Hg OU.

|

|

This patient presented with no visible signs of pathology. What would be your approach? Click image to enlarge. |

For More Information

Additional studies in this case included simple observation of her normal eyelid opening and eyelid closing. Health history questions were also asked to rule out connections to the facial nerve and issues of hearing (a place the facial nerve and auditory nerves have in common is along an anatomical pathway known as the cerebello-pontine angle).

What would be your diagnosis in this case? What is the patient’s likely prognosis?

Diagnosis

This patient is experiencing eyelid myokymia. The word myokymia is derived from the Greek words myo, meaning muscle and kyma, meaning wave. It is defined by random, involuntary, repetitive eyelid movements, which the patient can feel. The phenomenon is produced by uncontrolled electrical discharges and can involve any muscle within the body.1,2 With respect to the eye, it is known to primarily affect two structures: the eyelid and the superior oblique muscle.1-3 Patients with superior oblique myokymia present with a vertical jerk nystagmus, oscillopsia (a feeling that the world is jumping or moving) and transient binocular diplopia.3-6 In contrast, patients with myokymia of the eyelid present with a chief complaint of intermittent “oscillating,” “vibrating,” “flickering,” “quivering,” or “twitching” lid.3

Eyelid myokymia is the result of repetitive bursts of electrical discharge that stimulate the Muscle of Müller and the ciliary portion of the orbicularis oculi to contract.2,7 Most patients perceive the unexpected quivering as an annoyance; the spasms are not painful, nor are they so exaggerated that an observer could identify the episodes without being within a three-foot distance, looking directly at the affected area.

The phenomenon occurs cyclically (that is, it will come on, last for a month, leave and then resurface four months later, last for a month and then depart.) Anecdotally, it seems to arise at times of increased stress. Patients may be aware or unaware of their body’s emotional fluctuations, physical fatigue or illness. The episodes may also be connected to increased sympathetic tone, which can be voluntarily or unknowingly altered by nicotine, caffeinated drinks and some medicines.8 The episodes are transient, lasting from one to 10 minutes, and can occur once or multiple times during the day, lasting for a period of weeks to months. During normal physical and emotional periods, the episodes cease and the phenomenon moves into “hibernation,” often recurring during or following a trigger.2

Pathophysiology and Course

Traditionally, involuntary spastic twitching of muscles has been attributable to either: (1) tissues recovering from injury (2) demyelinating disease and neural response to compression or (3) mechanical irritation.1,3,6,9 In a study that examined acute unilateral facial paralysis, the symptom of transient long-lasting motor dysfunction featuring disorders of voluntary and involuntary movement was observed.10

After an ocular injury or facial traumatic event, some patients exhibit an increase in their spontaneous blink rate as well as a sustained low-level contraction of the muscles of the involved side.9,10 This occasionally leads to full blepharospasm.10 The finding was hypothesized by the authors to be due to increased excitability of the facial motor neurons and brainstem interneurons mediating recovering reflexes.9,10 One recognized mechanism of occurrence is full-blown “postparalytic facial syndrome.” This has been described as a type of muscular synkinesis (muscles responding together), myokymia and unwanted hemifacial contractions accompanying normal facial movements.9,10 Pathophysiological mechanisms include abnormal axonal branching after injury with aberrant axonal regeneration and enhanced motor neuronal excitability.9,10

Myokymia of the eyelid is generally considered to be a benign, self-limited disorder, with no consequence of permanent injury or paralysis.2 In a study of 15 patients where subjects had at least 12 months of follow-up, all patients whose symptoms began as unilateral, weekly or biweekly intermittent eyelid spasms who progressed to having daily spasms over several months demonstrated no manifestation of serious neurologic disease.2 Thirteen of the 15 patients (86.7%) underwent neuroimaging, with no abnormalities found; in this group, the myokymia resolved spontaneously in four individuals, with eight of the remaining nine opting to be treated with injection of botulinum toxin at regular intervals. Most of the patients who elected to receive injections reported improvement. Postparalytic facial dysfunction may occur following idiopathic facial nerve palsy (Bell’s palsy) and seems to be the result of increased background muscle activity and enhanced motor neuron recruitment.11

Recently, several reports have suggested that eyelid myokymia may, in very rare instances, be a presenting sign of multiple sclerosis.7,8 The described patients were young and seemingly healthy individuals with no relevant medical history or known drug use. In one case, the eyelid myokymia gave way after several weeks to facial myokymia involving the ipsilateral brow and cheek; in another, the eyelid twitching persisted and became continuous, prompting neuroradiologic investigation. In both instances, periventricular white matter lesions were noted on MRI of the brain.7,8

Differentials to Consider

A differential diagnosis is Meige’s syndrome, a condition in which patients frequently complain of photophobia and dry eye with increased blinking.12 The symptoms progress over a period of two to seven years, becoming more frequent, forceful and sustained. The condition often results in intermittent functional blindness due to inability to control eyelid spasms, which results in an inability to open the eyes.11-13

Abnormal auditory brain stem response potentials have been noted in patients who have benign essential blepharospasm and Meige’s syndrome, which implicates involvement of the brain stem.12 Additionally, abnormal levels of neurotransmitters have been demonstrated in the midbrain and brain stem nuclei of patients with Meige’s syndrome.12-14

Hemifacial spasm (HFS) is another differential diagnosis worthy of consideration in this case. Here, the entire face becomes involved rather than just the eyelid alone. This phenomenon typically is induced by vascular compression along the route of cranial nerve VII and tumors located at or in the vicinity of the anatomical landmark in the brain stem, known as the cerebello-pontine angle.15 Tumors local to the foramen magnum have also been implicated.16 The mechanism of the facial contractures is mass effect resulting in mechanical irritation.15,16

Benign myokymia is diagnosed by the company it keeps and is a diagnosis of exclusion. Patients who pose the question in passing, “Why does my eyelid twitch sometimes?” are most likely experiencing benign eyelid myokymia.1-16 The diagnosis is solidified by confirming the presence of the classic clinical features: (1) episodic, (2) limited to the eyelid, (3) painless, (4) no effect on function, (5) intermittent throughout the day, (6) cyclical and (7) no other loss of neurologic function or signs or involvement of other facial muscle groups.

Chronic isolated eyelid myokymia is generally considered a benign condition. It does not progress to other facial muscles or elaborate into other facial movements or disorders. If these complications are observed, more significant systemic disorders such as multiple sclerosis or neoplastic disease must be considered and ruled out. Since eyelid twitching and HFS are associated with brainstem disease, persistent cases warrant referral to neurology or neuro-ophthalmology.

Management of the Case

Treatment for eyelid myokymia typically consists of behavior modification in the form of stress reduction, elimination of nicotine and/or caffeine, and rest. Patients should be educated that the condition has a name, and should be reassured that in almost all instances it is benign. They should be counseled regarding signs that would indicate the need for additional testing or consultation, such as persistence and/or worsening.

Direct forms of intervention may include discontinuation of provoking medications (where feasible), cold compresses or consumption of tonic water with quinine (based on anecdotal reports). In more severe or intolerable cases, pharmacologic intervention with topical beta blockers, anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine (100mg-200mg PO BID-QID), gabapentin (100mg PO BID, building to 300mg-600mg per day) or local eyelid injections of botulinum toxin.2,3,6,10

Excessive benign eyelid myokymia responds well to botulinum toxin injection. Isolated eyelid myokymia is rarely associated with other neurologic diseases.

Dr. Gurwood thanks Dr. Al Kabat for his contributions to this case.

Dr. Gurwood is a professor of clinical sciences at The Eye Institute of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University. He is a co-chief of Primary Care Suite 3. He is attending medical staff in the department of ophthalmology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Mancias P, Butler IJ. Trigeminal myokymia in a young girl. J Child Neurol. 2003; 18(8):572-4. 2. Banik R, Miller NR. Chronic myokymia limited to the eyelid is a benign condition. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24(4):290-2. 3. Straube A. Therapeutic considerations for eye movement disorders. Dev Ophthalmol. 2007;40:175-92. 4. Williams PE, Purvin VA, Kawasaki A. Superior oblique myokymia: efficacy of medical treatment. J AAPOS. 2007;11(3):254-7. 5. Ruttum MS1, Harris GJ. Superior oblique myectomy and trochlear resection for superior oblique myokymia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(4):563-5. 6. Foroozan R, Buono LM, Sergott RC et al. Jumping Jack Flash. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51(1):63-7. 7. Palasí A, Martínez-Sánchez N, Bau L, Campdelacreu J. Unilateral eyelid myokymia as a form of presentation of multiple sclerosis. Neurologia. 2013;28(3):187-9. 8. Barmettler A, Dinkin MJ, Lelli GJ. Eyelid myokymia: not always benign. Orbit. 2011;30(6):289-90. 9. Valls-Solé J, Montero J. Movement disorders in patients with peripheral facial palsy. Mov Disord. 2003;18(12):1424-35. 10. Valls-Sole J, Tolosa ES, Pujol M. Myokymic discharges and enhanced facial nerve reflex responses after recovery from idiopathic facial palsy. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15(1):37-42. 11. Valls-Solé J. Facial nerve palsy and hemifacial spasm. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;115:367-80. 12. Faucett, D. Essential blepharospasm. In : Yanoff, M., Duker, J.S. Philadelphia, PA, Mosby 1999:7.10.1–7.10. 4. 13. Yoshimura, R., Kakihara, S., Soya, A., Ueda, N., Shinkai, K., Nakamura, J. Effect of clonazepam treatment on antipsychotic drug-induced Meige syndrome and changes in plasma levels of GABA, HVA, and MHPG during treatment. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001;55(5):543-6. 14. Kirton, C.A., Riopelle, R.J. Meige syndrome secondary to basal ganglia injury : a potential cause of acute respiratory distress. Can J Neurol Sci 2001;28(2):167–73. 15. Choi SK, Rhee BA, Lim YJ. Hemifacial spasm caused by epidermoid tumor at cerebello-pontine angle. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;45(3):196-8. 16. Matsuda M, Akutsu H, Yamamoto T, et al. Hemifacial Spasm Associated with Contralateral Foramen Magnum Meningioma. World Neurosurg. 2016;89:729.e11-3. |