|

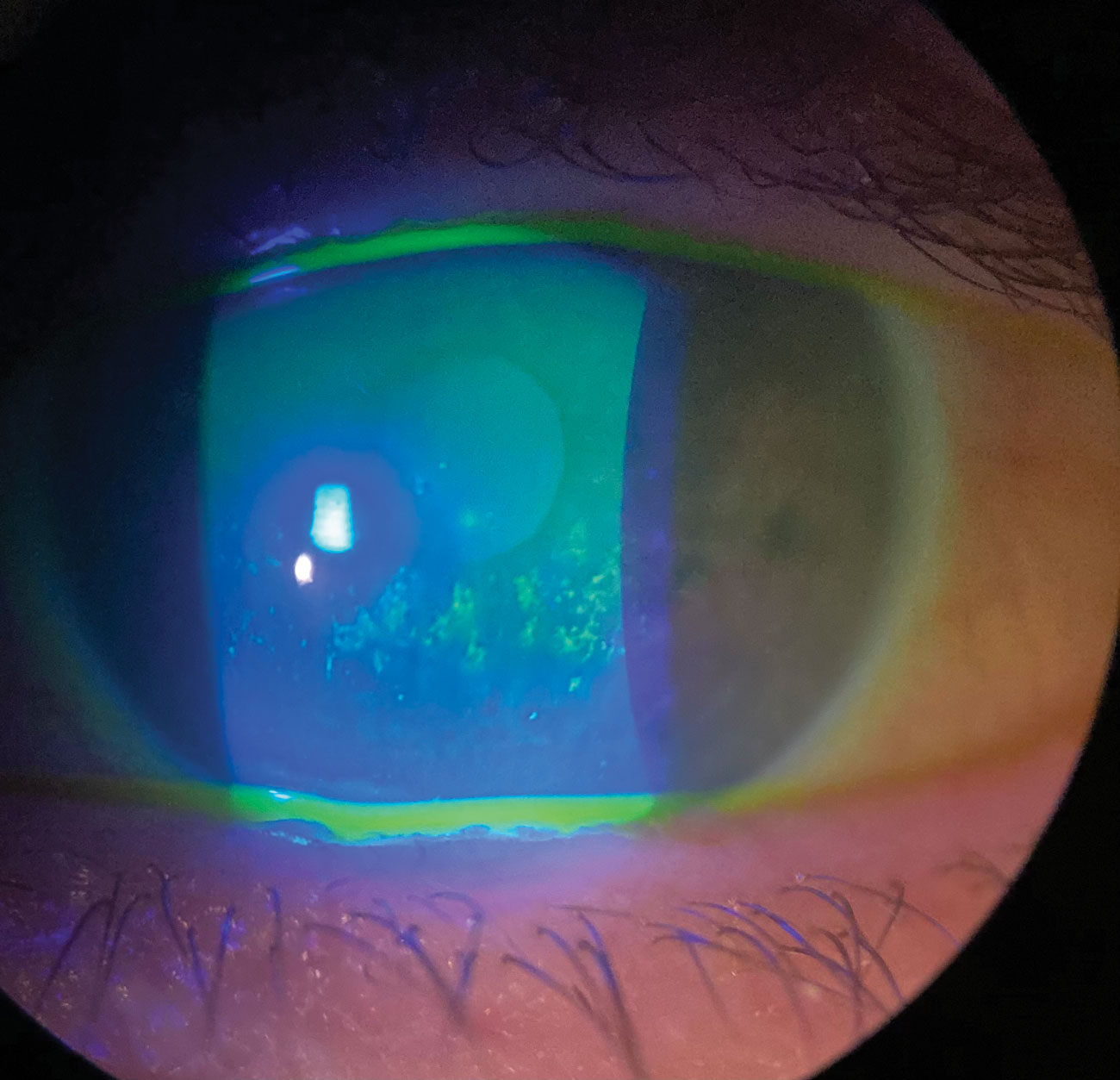

Depression and anxiety were identified as independent risk factors for dry eye diagnosis, with association strength varying by age, sex, race and residence region. Photo: Pam Theriot, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Although dry eye disease has been studied exhaustively, a lesser-known facet of the condition concerns the impact of demographic characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity in the American geriatric population. According to the authors of a new study, their work is the first to reveal significant psychological as well as racial differences in the prevalence of dry eye after adjusting for demographic covariates like climate regions and income. The team, from Mt. Sinai in New York and Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore, found dry eye twice as common in those with depression and anxiety, in addition to significant demographic differences.

Data was collected from a 2011 nationwide sample of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, residential area, climate region and income, along with psychiatric comorbidities including depression and anxiety, were collected.

Among 21,059 patients with clinically significant dry eye, women had higher odds of the condition compared with men—with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.03 for women—consistent with other reports on sex differences in prevalence. Asian(1.85 OR) and Native American (1.51 OR) patients had increased odds of having dry eye compared with white patients, while Black patients were less likely to have dry eye (0.83 OR). The authors commented, however, that this discrepancy may be due to the underdiagnosis of dry eye in Black patients.

“The literature has shown that minority patients in the United States (including Asian, Black and Hispanic) present with worse baseline dry eye parameters, including increased conjunctival staining, corneal staining and tear osmolarity compared with white patients,” the authors explained. “Black patients are also more likely to be self-referred for dry eye and more likely to have dry eye discovered incidentally after presenting for an unrelated ophthalmic complaint.”

Patients aged 75 to 84 years (1.49 OR) and those 85+ (1.54 OR) were more likely to have dry eye compared with those aged 65 to 74 years.

Regionally, populations in the West had the highest dry eye odds ratio (1.38), while people living in the Upper Midwest were found to have the lowest (0.76).

Depression and anxiety were associated with higher odds of having dry eye—1.95 OR and 2.22 OR, respectively—while having both together raised the odds ratio to 2.38.

There is evidence supporting the presence of dry eye precipitating psychiatric illness, including increased dry eye severity being associated with decreased self-reported quality of life and sleep quality. “Notably, Sayegh et al reported a correlation between increasing Ocular Surface Disease Index scores with decreasing scores on the mental health component of the Short Form- quality of life survey,” the authors explained in their paper for Cornea on the work. The strength of the association increased with follow-up duration. “This suggests that mental health status may become more closely linked to dry eye severity with increasing disease duration.” Conversely, they point out, “psychiatric illnesses may precede dry eye as these conditions are implicated in neuropathic pain syndromes and are known to affect pain amplification. The ocular discomfort experienced by patients with these comorbidities may be related to somatization instead of ocular surface desiccation. Indeed, depression and anxiety are closely associated dry eye symptoms, but not clinical signs of dry eye.”

The authors found that the association between depression, anxiety and dry eye decreased with increasing age, while the opposite was observed in a previous study where anxiety and depression were more highly associated with dry eye as age increased in a younger population (ages 18 to 65 years).

“Possible factors underlying this association reversal include the possibility of generally healthy older beneficiaries using medical services less as transportation becomes more challenging,” the authors explained. “Elderly beneficiaries with longstanding, well-managed dry eye may also no longer need regular check-ups and were not seen for dry eye in the 2011 calendar year.

Li G, Garzon C, Klawe J, et al. Demographic and psychiatric associations with dry eye in a Medicare population. Cornea. January 20, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. |