Dry eye disease can be a frustrating and perplexing illness for both patient and doctor. Many patients present with bags full of artificial tears and other medications that have failed to bring them lasting relief. They are often desperate for answers, comfort and solutions. Doctors are eager to help, but may struggle to offer a novel treatment for a patient who has been disappointed by fruitless previous efforts. But consider a different, perhaps less common, scenario: a patient has no complaints, no bag of drops and no exasperation, but has all the signs of severe dry eye.

Research shows fewer than 60% of dry eye patients are symptomatic—which can make things tricky.1 What do you do? To treat or not to treat, that is the question.

A Symptom-Driven Illness

While a debatable concept to some, dry eye disease is essentially a symptom-driven illness. Patients often present to the office reporting discomfort ranging from mild irritation to agony. They present with visual complaints that can range from intermittent fluctuations to substantial decreases in functional acuity. Impact on their activities of daily living may vary from limiting time at the computer to the inability to drive a car.

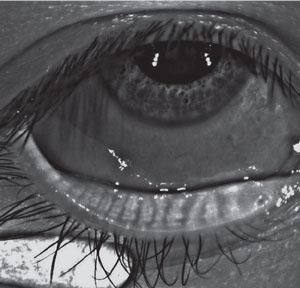

| |

| No corneal defects are found in this symptomatic patient. |

Considering an estimated 40% of patients are prompted to visit their primary care provider based on the complaint of pain, it should come as no surprise that dry eye patients are likewise propelled into our office because of symptoms.2

Addressing subjective ailments is an essential part of being a doctor—showing empathy for our patient’s plight builds a strong sense of rapport. Almost all eye care providers at some point in their career have considered if the patient is 20/20 or “20/happy”—sometimes, there is a big difference. But treating subjective complaints, particularly when few objective ones reinforce a dry eye diagnosis, can be exceptionally frustrating for doctors, considering optometry is a data-driven profession. While providing relief for patients is paramount, quantitative diagnostic testing should support our treatment decisions, and in dry eye care it regularly does not.

Objective Testing

Dry eye surveys and questionnaires offer some objectivity to symptoms. The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) has excellent reliability and validity, as well as good sensitivity and specificity.3 It discriminates well between normal, mild to moderate and severe cases. Unfortunately, it has some limitations. OSDI has consistently failed to correlate well with traditional objective dry eye testing, namely Schirmer’s test type 1, in studies.4 Of course, this may speak more to the diversity of the diagnosis than the accuracy of the OSDI.3

Another limitation is that OSDI is designed to evaluate ocular surface disease (OSD), which is a much broader term encompassing many diagnoses, not just dry eye. For example, patients with evaporative dry eye due to meibomian gland dysfunction could have a poor OSDI with essentially normal Schirmer’s testing; similarly, a patient with conjunctivochalasis may score high on the OSDI with no form of dry eye disease at all.

Use of vital dyes like 2% sodium fluorescein and 1% lissamine green are useful in analyzing the ocular surface. Some practitioners choose one or the other, but both are required to get a detailed picture. Fluorescein is used to identify desiccated or injured cells and to perform a fluorescein tear break-up time (FTBUT). Lissamine green, on the other hand, stains dead or devitalized cells.5 Lissamine green is useful in evaluating conjunctival damage, conjunctivalchalsis and the line of Marx along the lid margin. A combination drop, Fluramene (lissamine green 0.5% and sodium fluorescein 1.0%, EyeSupply USA), is convenient because it requires only one instillation vs. multiple strips. However, it stains the eyelids and can be difficult to remove once applied.6 The vital dyes may be the first indicator that the patient’s signs and symptoms don’t match up.

The Emotion Factor

Lack of clinical signs doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem. Managing a patient’s symptoms may not be exclusively an ocular health concern either. Research shows patients with dry eye disease are more vulnerable to anxiety and depression. Self-rated anxiety scores correlated with OSDI and education level, and self-rated depression scores correlated with OSDI alone.7 Neither anxiety nor depression showed a connection to age, gender, household income, tear break-up time (TBUT), Schirmer’s test 1, fluorescein staining or visual acuity.7 How patients view their condition and report symptoms may create a clinical mismatch, yet it makes the obstacle no less real. The emotional component of dry eye disease tends to make the patient’s care even more delicate and complicated.

The Symptomatic Patient

Let’s consider Laura, a 64-year-old white female who presented for a dry eye evaluation several months ago. Laura was miserable. She was unable to work on her iPad for more than five minutes at a time and could no longer drive a car. The pain was palpable for both her and her husband, who served as her constant companion and chauffer. Laura’s subjective complaints and dry eye history were extremely lengthy—she had tried it all. A multitude of artificial tears, ophthalmic medications and punctal cautery brought no relief. Her complaints were profound, but the apparently insignificant objective findings left me scratching my head. Laura’s complaints could be psychosomatic; however, after nearly 15 years of practice, I consider psychosomatosis a diagnosis of exclusion.

| |

| Diffuse lissamine green staining is evident in this asymptomatic patient. |

Laura’s acuity was 20/20 (though not 20/“happy”). Her OSDI score was 100 (out of 100). Her tear osmolarity was 290/306 OD/OS. Lipiview measured both lipid layer thickness (LLT) at 81/79 OD/OS and partial blinks at 6/12 OD/OS. Her non-invasive keratograph break-up time (NIKBUT) was 6.63/7.87 OD/OS. ZoneQuick was 15/15mm OD/OS. Infrared meibography showed modest meibomian gland atrophy but no frank fallout. At the slit lamp, she had no blepharitis or lagophthalmos and did not exhibit increased lid laxity relative to her age. No lissamine green or fluorescein stain was identified on the conjunctiva or cornea. None of the additional testing was outside of normal limits.

While some of Laura’s objective testing pointed to the diagnosis of dry eye disease with likely a mixed-mechanism origin, none of the findings appeared to warrant the extreme symptoms she reported. With incompatible subjective and objective testing, what is a doctor to do? Without the luxury of knowing her lengthy and failed history with artificial tears, one might be tempted to throw a lipid-based tear on the problem and schedule a follow-up. But that was not going to cut it for Laura or her husband, who wanted her to find relief as much as she did.

Thus began our winding journey through Laura’s dry eye treatment. In search of solace, we have tried a plethora of artificial tears, cyclosporine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, cellulose ophthalmic inserts, scleral contact lenses and, finally, thermal pulsation with Lipiflow. She was tested for Sjögren’s syndrome and had a complete rheumatology work-up. All tests were negative. We are still on the journey with only bouts of short-lived relief.

Most recently, Laura elected to have intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy for dry eye. Ideally, her mild rosacea will regress with treatment, which offers benefits for both cutaneous and ocular rosacea. IPL shuts down blood vessels that bring inflammatory mediators to the lid margin and decreases the amount of bacteria on the skin. IPL may also decrease the presence of parasites on the skin. As the rosacea subsides and the telangiectasias are minimized, symptoms may also diminish. It is too soon to know the outcome, but I’m still optimistic that she will find relief.8,9

Preventative Medicine

Symptomatic patients like Laura are easily persuaded to try various treatments, but what about the patient who thinks all is well—until testing reveals otherwise? Although “asymptomatic” means without symptoms, it certainly doesn’t mean without illness or disease. People regularly walk through life with undiagnosed conditions that range in severity from benign to life-threatening. Treatment for hypertension, for example, has increased since 1999 due to an increased public awareness, yet an estimated 20% of adults in the United States have hypertension and still don’t know it.10 Untreated high blood pressure can contribute to heart attack, stroke, chronic heart failure and kidney disease.3 Similarly in eye care, glaucoma is an insidious disease that offers few, if any, red flags to patients before diagnosis.

| |

| In this symptomatic patient, essentially normal meibography reveals no atrophy or tortuosity of the glands. |

Preventative medicine, as defined by the American Board of Preventative Medicine, is health care “focusing on the health of individuals, communities and defined populations. Its goal is to protect, promote and maintain health and well-being and to prevent disease, disability and death.”5 Public awareness of preventative medicine is on the rise, and patients are more likely than ever before to pursue cholesterol screenings, mammograms and the like. They seek these results not because they have symptoms, but rather because they acknowledge that earlier diagnosis and treatment often leads to better prognosis.

Historically, dentistry has done an exceptional job of prioritizing preventative care, recommending patients return twice a year for cleaning and evaluation. Likewise, eye care professionals should recommend biannual evaluation for patients who are more susceptible to OSD under the notion of preventative care. Ultimately, alerting patients to potential symptoms may head off their future frustrations and give the doctor a leg up on initiating early treatment.

It’s clear to see the motivations to treat asymptomatic hypertensive and glaucoma patients, but should dry eye disease—which is rarely sight-threatening—be addressed as aggressively? Research supports improved objective and subjective results with treatment; however, most studies acknowledge some element of patient-reported symptoms.11 When it comes to asymptomatic patients, some may consider the adage: “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Still others may fancy themselves cowboys, and try to “head it off at the pass.” Neither approach is absolute.

Education

If patients don’t have symptoms to motivate them, perhaps patient education will. If you elect to treat the asymptomatic patient, proper education is essential. Most doctors readily acknowledge that ocular surface disease does not always mean that the predominant symptom is dryness. In fact, “dry eye” is often a misnomer to patients. They require education to embrace the fact that ocular surface disease may manifest as a decrease in quality and quantity of vision, as well as comfort-related symptoms. The patient must understand the chronic, multifactorial nature of dry eye disease, and that the symptoms, though absent now, cannot be outrun forever. Carefully drawing parallels to silent diseases like hypertension may prove beneficial, but don’t sound too dramatic. Let objective diagnostic testing provide the most persuasive argument. After all, a picture, whether it’s meibography or external photography, is worth a thousand words. Once the chronicity of the condition is appreciated, some patients may be won over. For others, slowly chipping away with more conventional educational means such as emails and mailings may help. Often there can be an additive effect to gradual education and patients eventually reach that “ah-ha” moment.

The Asymptomatic Patient

Consider Sarah, a 60-year-old white female, who had mild dry eye symptoms that were identified at a yearly comprehensive eye examination. As a college professor, she reads voraciously for both work and pleasure. Additionally, she spends hours researching for a novel she is writing. Near demands for Sarah were exceptionally high, but she was only aware of occasional fluctuations in vision. Upon examination, her visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. Her OSDI score was 28/100 and SPEED was 4/28. Tear osmolarity was 325/333 OD/OS. Lipiview revealed excellent blink performance but a staggeringly low LLT of 30/28 ICUs OD/OS. RPS InflammaDry was faintly positive, and ZoneQuick was over 30mm OD/OS. NIKBUT was 7.58sec and 6.76sec, respectively. At the slit lamp, Sarah had no blepharitis or lagopthalmos. However, she did present with moderate conjunctival staining with lissamine green in both eyes.

| |

| Significant meibomian gland atrophy in an asymptomatic patient. |

The signs that Sarah exhibited were remarkable compared to those of our patient, Laura. However, she thought little of the diagnosis. In fact, none of this was news to her. She was previously diagnosed with dry eye and prescribed cyclosporine. Sarah discontinued the drops several years ago after only a few weeks of reported compliance because she felt nothing in her life had changed. It was difficult to argue with her. Cyclosporine is indicated to increase tear production, but not necessarily decrease near vision fluctuations, which was the patient’s only aggravation from the diagnosed dry eye disease. Lack of education probably set up both Sarah, and the medication she was prescribed, for failure.

Can, or should, Sarah be re-engaged as an active participant in her dry eye maintenance? I chose to pull her back into the fold. With gentle persuasion and education, she has dutifully returned for follow-up exams and maintained moderate compliance with recommended therapies. We started with lipid-based artificial tears and a warm, silicone-beaded mask used two times per day. While the objective testing points toward an evaporative dry eye disease and Lipiflow would be warranted, I elected to stick with a more basic course. The thermal pulsation treatment would have expedited improvement in her testing; yet, I tend to proceed with conservatism and caution in asymptomatic patients especially when it comes to presenting an elective procedure. Her modest dedication to her own condition satisfies me for now. The dry eye disease is likely to progress as the years go on and, hopefully, Sarah will recognize that she has a partner in piecing together this ever-changing puzzle.

When You Should Treat, and When You Shouldn’t

Did I make the right choice for Sarah? All practitioners have to answer that question for themselves when a similar patient presents. And the answer may change. Some may be more easily enrolled in preventative care while others won’t appreciate the value or flat out consider it unnecessary. We often coach our staff not to prejudge how much a patient is willing to pay for frames and lenses. Equally, we should proceed with caution and not assume which patients will and won’t “buy in” to preventative care. Patients who list a multitude of supplements may be your prime candidates, but a patient who recently had a heart attack may be turning over a new leaf in his or her life and may be just as willing to listen.

A detailed case history is the key to choosing the best testing that finally provides the most accurate diagnosis. Consider occupation and avocation in addition to medications, typical environmental conditions and failed therapies. Special attention should also be paid to patient populations predisposed to dry eye disease like those with thyroid eye disease, autoimmune disease and diabetes.

There are occasions when asymptomatic patients must be treated to prevent greater risk: if vision is consistently compromised; the ocular surface has significant irregularities, increasing susceptibility to bacterial invasion; or if patients have decreased corneal sensitivity or a neurotrophic cornea, because they may never elicit a response.

Dry eye disease is a confounder on many levels. The multifactorial nature of it casts slings and arrows from every direction. What relieves symptoms may not improve signs, and what works in June is a failure in January. We can succumb to the frustration that there are no quick fixes or easy answers, or accept the challenges that dry eye disease presents. There are millions of sufferers across the United States, and numbers are only expected to climb as baby boomers age. Doctors will likely encounter more puzzling patients in their practices, and they will have to make the decision to go “all in” or “let it ride.”

Dr. Hauser is an assistant professor at Southern College of Optometry in Memphis, Tenn., clinical development consultant for TearWell Advanced Dry Eye Treatment Center and founder of Signal Ophthalmic Consulting. She serves as a consultant for TearScience.

1. Bron AJ, Tomlinson A, Foulks GN. Rethinking dry eye disease: a perspective on clinical implications. Ocul Surf. 2014 Apr;12(2 Suppl):S1-31.2. Mantyselka P, Kumpusalo A, Kauhanen J, et al. Pain as a reason to visit a doctor’ office: a study in Finnish primary healthcare. Pain. 2001 Jan;89(2-3):175-80.

3. Schiffman RM, Jacobsen CG, Hirsch J. Relability and validity of ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000 May;118(5):615-21.

4. Lemp MA. Report of the national eye institute/industry workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes. CLAO J. 1995;21:221- 32.

5. Abelson M, Ingerman A. The dye-namics of dry-eye diagnosis. Review of Ophthalmology. 2005 Nov;12(11). www.reviewofophthalmology.com/content /i/1311/c/25254/.

6. Bowling E. Double vital dye staining. Vision Care Professional. 2012 March. www.visioncareprofessional.com/emails/managingdryeye/newsletter21.asp.

7. Wen W, Wu Y, Chen Y, et al. Dry eye disease in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders in Shanghai. Cornea. 2012 Jun;31(6):686-92.

8. Kent C. Intense pulsed light: for treating dry eye. Review of Ophthalmology. 2010 Nov;17(11). www.reviewofophthalmology.com/content/i/1353/c/25857/.

9. Elmnasser N, et al. Bacterial inactivation using pulsed light. Acta Alimentaria. 2007;36:3:401-8.

10. High Blood Pressure Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

11. Greiner J. Long-term (12-month) improvement in meibomian gland function and reduced dry eye symptoms with a single thermal pulsation treatment. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2013 Aug;41(6):524-30.