|

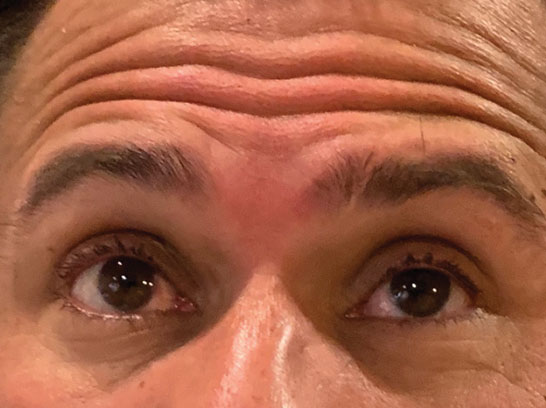

A 44-year-old male presented to the emergency room with a two-day onset of dizziness and diplopia. He felt the dizziness was worse when walking and seemed to be due to the imbalance from his vision. He denied any additional symptoms and otherwise has been in good health. The patient is originally from Honduras and moved to the United States eight years ago. His medical history is unremarkable, and he is not currently taking any medications.

His visual acuities were 20/70 OU. His extraocular muscle movements showed full right and left gaze; however, his downgaze was about 70% reduced, and his upgaze was 100% reduced. Both of his pupils were unreactive to light, and the left pupil was larger than the right by approximately 1mm to 2mm.

Although the pupils did not react to light stimulus, they did constrict when the patient fixated on a near target. Additionally, there was a subtle convergence-retraction nystagmus noted. His intraocular pressures were normal at 17mm Hg OU. His anterior and posterior segment exam was completely normal.

|

This patient presented with dizziness and the inabilty to look upward. |

Ring Around

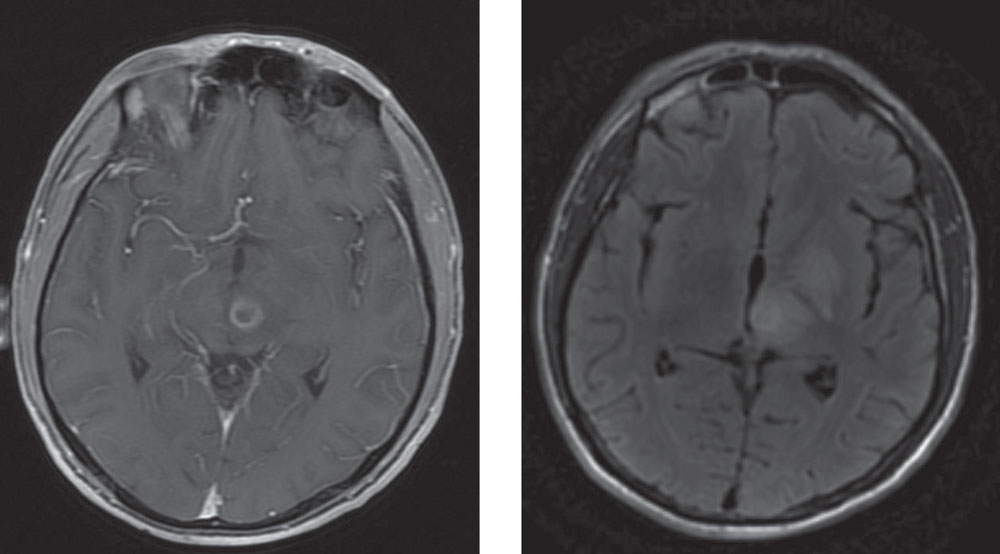

The pupil and motility findings were consistent with dorsal midbrain syndrome (DMS), also known as Parinaud’s syndrome. Because of these findings, the team ordered a brain computerized tomography (CT) scan, which showed edema in the left basal ganglia with regional mass effect. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) was then ordered for further evaluation and showed three ring-enhancing lesions at the left midbrain, left basal ganglia and left temporal lobe with regional vasogenic edema.

These ring-enhancing lesions were most consistent with either metastatic disease or infection. Subsequently, the patient was admitted with neurosurgery and infectious disease consultations. His chest, abdominal and pelvic CT scans were all unremarkable, and his cerebrospinal fluid cytology was normal—the brain lesions were unlikely to be metastatic.

An infectious disease work-up revealed the patient to be human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive with a CD4 cell count of 96. Serum toxoplasmosis IgG was markedly elevated, and a lumbar puncture showed elevated cerebrospinal fluid toxoplasmosis IgG as well.

The patient was diagnosed with HIV, and his brain lesions were consistent with an opportunistic central nervous system (CNS) toxoplasmosis infection. The neurosurgeon did not recommend any acute surgical intervention, and the patient was treated with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine and leucovorin.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) was held initially until his opportunistic toxoplasmosis infection improved to avoid the risk of inducing immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).

The patient remained hospitalized for approximately one month while he was receiving treatment for his CNS infection. Prior to his discharge, we ordered a repeat MRI that showed improvement of all three ring-enhancing lesions, with significant improvement of the associated edema. A repeat assessment of his ocular motilities showed improvement in his upward and downward gaze.

He still reported diplopia and some vision difficulties, but his upward gaze improved from a 100% limitation to about a 60% to 70% limitation. The downward gaze improved from a 70% limitation to about a 30% limitation. His pupils were now similar in size with only 0.5mm of anisocoria and started to show some constriction to light stimulus.

The patient was discharged with instructions to take sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, leucovorin and pyrimethamine and later scheduled to start ART in a health clinic. He was also instructed to follow up in three months to reassess his ocular motilities.

|

| This axial MRI is able to show the ring-enhancing lesion (left). The edema surrounds the lesion, with compression around the posterior commissure (right). |

Discussion

The premotor pathways for vertical eye movements are located within the dorsal and tegmental midbrain and include the rostral interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (riMLF) and the posterior commissure. Dorsal midbrain syndrome is a vertical gaze palsy that affects these structures and presents clinically with impaired vertical eye movements, light-near dissociation of the pupillary response and convergence nystagmus on attempted upward gaze.1

Pineal lesions exerting pressure on the midbrain are the classical cause of DMS, however primary lesions within the midbrain can be responsible as well.1 Ischemia, hemorrhage, neoplasms and infectious or demyelinating processes also have all been reported.1

There is no specific treatment for DMS, and the prognosis is dependent on the underlying cause, extent of damage and treatment.2 Any residual ischemia, atrophy or necrosis to the involved structures or damage from treatments, such as tumor resection or radiation, may prevent full recovery of vertical gaze.

In managing our patient, the first step was to identify the intracranial process that was causing DMS. The ring-enhancing lesions, specifically the one within his brainstem, were compressing around the posterior commissure with edema in the midbrain, correlating with his clinical presentation.

The next step was to determine the etiology of these peripheral enhancing lesions. The underlying cause of ring-enhancing lesions is influenced in part by the immune status of the individual.3

Malignancy (primary or metastatic) tends to be the more common cause in immunocompetent individuals, while lymphoma and toxoplasmosis are often the cause in immunocompromised individuals.3 Our patient presented with no prior medical issues, but a thorough work revealed he was HIV positive, was immunocompromised and had developed a CNS toxoplasmosis infection.

While neurology or infectious disease specialists typically perform these evaluations, an optometrist’s role is important in a case such as this because the patient only presented with symptoms of diplopia. Localizing the source of the diplopia and the appropriate neuro-imaging helped to direct their work-up.

Lastly, in regards to management, the toxoplasmosis infection was treated and better controlled prior to starting the patient on ART. CD4 cells are suppressed due to HIV infection, and, if ART therapy is started simultaneously with treatment of the opportunistic infection, CD4 cells may rapidly increase, causing a significant inflammatory response.4

Although IRIS is generally self-limiting, it has a high mortality rate in the setting of opportunistic infections involving the CNS as seen in our patient.4 Because of the potential for IRIS, ART was held initially to prevent this rapid increase of CD4 cells and the syndrome from developing.

While DMS is a rare clinical presentation, it’s caused by brain stem dysfunction and often is a result of fatal diseases, if not treated appropriately. Early diagnosis and management are essential for patient survival and positive outcomes.

| 1. Shields M, Sinkar S, Chan W, Crompton J. Parinaud syndrome: a 25-year (1991-2016) review of 40 consecutive adult cases. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95:792-3. 2. Yiu G, Lessell S. Dorsal midbrain syndrome from a ring-enhancing lesion. Semin in Ophthalmol. 2012;27(3-4):65-8. 3. Chakraborty S. Multiple ring-enhancing lesions in a patient with unilateral limb jerking. Cent Eur J Med. 2014;9(3):391-3. 4. Sharma S, Soneja M. HIV and Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS). Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(6):866-77. |