|

An optometrist in 1891 likely spent his days doing refraction—and little else. Such was the primacy of vision assessment to the profession in its earliest incarnation. As optometry splintered off from opticianry in the late 19th century, it elevated the correction of refractive error to an art form. Gone were the days of so-called spectacle peddlers, who sold glasses out of a box and cajoled or flat-out bamboozled customers into thinking their resulting vision was the best it could be. Often, it was not.

With aspirations to more professional standards of evaluation and correction, optometry made its bones. The “oculist” physicians of the day didn’t bother much with optics and refraction, as they were more concerned with eye health and disease. In the gap between the spectacle peddlers and the oculists, optometry flourished.

A look back at this publication’s content during its first few decades reveals an optometric world in which articles on optics, vision testing and refractive correction methods were its stock in trade.

|

| Photo: Philip Tribble, Southern College of Optometry. |

Over the years, refraction has remained a mainstay of the discipline even as attention shifted to ocular health when optometrists gained new rights and responsibilities in disease diagnosis and treatment.

Fathers of Optometry

Since its inception as The Optician in 1891, this publication has turned to thought leaders to share their perspectives and priorities, including the famous Charles Prentice and Andrew Cross, considered the “fathers of optometry.”1

Drs. Prentice and Cross, complementing one another through their contrasting roles and strengths, propelled the profession to new intellectual and organizational heights.1 Prentice “provided the spark” of ambition among refracting opticians for an appropriate professional identity and a legal status to match.1 Prentice founded Columbia University’s optometric program, and Cross, in turn, nurtured the program from its infancy as active director while also using his organizational acumen to lead the successful legislative campaign in New York State.1

Charles Prentice himself penned the first feature article in our debut issue in January 1891: “A Metric System of Numbering and Measuring Prisms.” Building on other late 19th century publications of his, Prentice’s article was ground-breaking—it tore down the old schema of prism numbering and finally took into account the indices of refraction in prism designation. No longer was the “wedge” used to number your prisms!2

“Looking at the paper, well, I’m floored. It’s not until 1891 that we get the first proposal for using the unit of measure we now call the prism diopter? Holy cow,” says Paul Harris, OD, of Southern College of Optometry. “I would have expected that term to be around from the earliest creation of lenses—this is astounding. To imagine prior to this they used the angular measure of the wedge!”

A 1901 article by Andrew Cross, “Dynamic Skiascopy, or the Control of Accommodation in Estimating Errors of Ocular Refraction with the Retino-skiameter,” emphasized the imprecise nature of the art.3 “There is no system at present,” he says in the article, “that can determine absolutely the ocular refractive errors in every case, whether one is using objective or subjective methods.”3

Marc Taub, OD, of Southern College of Optometry, asserts the validity of Dr. Cross’ work. “I love the first paragraph, in which he talks about the word ‘estimating’ in the title of the paper,” says Dr. Taub, adding that Dr. Cross is correct in his statement that no systems exist that can be relied upon in all cases for the absolute determination of refractive error.

“Essentially, the data points of retinoscopy, refraction, binocular balance, etc., are just that—data points. They should not be taken as absolutes,” says Dr. Taub. “Refractive correction is in fact a negotiation between examiner and patient.”

Dr. Cross’ description of the behavior of the shadow remains true, according to Dr. Taub, but he says that sometimes ODs miss the strategic mark. “Too often, practitioners are aimed at the number, and not the quality or behavior, he says. “The brightness, symmetry and behavior of the reflex tell you so much about the way a patient uses their visual system but you have to look!”

Seeing the Light

You didn’t have to be a Prentice or a Cross to get published, however. Pick up any early issue of The Optical Journal and Review of Optometry—the pulication’s name from 1910 to 1977—and you’ll find everyday refractionists sharing their techniques of vision testing with their colleagues, some of which still hold up today.

A piece from 1914, at the break of World War I, describes the key points of performing skiametry and retinoscopy. Written by R.L. Hill of Campbellsville, Ky., over a century ago, it nevertheless describes principles of practice that wouldn’t be out of place in an optometric office of 2016, such as how illumination level affects outcomes.4 “I never make the room too dark,” Dr. Hill says, “for all the darkness we want is just enough to see distinctly the reflections from the mirror.”4

|

| Andrew Cross described and demonstrated his dynamic skiascopy technique in 1901, emphasizing the imprecise nature of the art. Click to enlarge. |

The equipment, however, reflects a different era. “The lights that I use in skiametry,” Dr. Hill says, “are situated behind and above my examination chair, being adjustable, so that when my patient is seated the light will be just behind and above his head.” An obvious sign of the times: Dr. Hill’s lights are “asbestos lined” to block light out except for at specific points and one inch in diameter in order to “cut off all rays of light excepting those we want to use,” he says.4

He continues with the exam. After “throwing the light” across the meridian of the eye from right to left and back again, he makes note of the directions the light and shadows take with respect to the mirror and discerns its movements accordingly.4 Using the hypothetical instance of the shadow going with the mirror, he says,“so I know by the reflected rays not focusing in front of me [that] my patient’s far point is behind me, thus showing me that I have a case of low myopia, of hypermetropia, or that the eye is emmetropic, and that it will take a plus lens to focus the reflected rays on my retina, or just in front of me.”4

And so Dr. Hill neutralizes the motion of the shadow, “or barely reverses it,” as he adds plus power/plus lenses in small increments, and takes into account the distance between himself and the patient to account for the correction in the meridian on which he is focusing.4 “We will say that in this instance, it takes plus 3.00 D,” he says, using two significant digits to the right of the decimal—Dr. Hill is a precise optometrist.4 “So this meridian is hypermetropic to the amount of 3.00 D,” he says. But, after taking into account the distance of one meter from his patient (the equivalent of 1.00 D), he deducts it and concludes with a final result of 2.00 D in the meridian.4

Ancestors of OptometryBy Bill Kekevian, Senior Editor No one knows for sure when spectacles were invented. The oldest known reference to spectacles in the Western world, however, dates to 1276 when Roger Bacon (philosopher, scientist, and—dubiously—alchemist) wrote of “a certain glass that made small letters appear larger.”

It would take until the 1600s to figure out why certain lenses had that capability—or even how the anatomical lens works. The first to hypothesize the mechanism of the retina, Johannes Kepler, had to temporarily delay his life’s work to defend his mother in trial against a charge of being a witch and casting spells.1 In those intervening 300 plus years, early physicians developed a disdain for spectacles and advised against their use.2,3 Those who sold the “crude, ugly, unscientific” spectacles of this era “obeyed no mathematical laws.”2 Early ophthalmologists—“oculists” as they were known—such as the 16th century German Georg Bartisch, “bitterly opposed the use of spectacles.”3 With its oldest known ancestors “alchemists” and “street peddlers,” optometry’s reputation was sullied before it was even named.2 One hundred and seventy years after Kepler’s mother was cleared of witchcraft, the world changed significantly. Notably, The American Revolution established a new nation. A citizen of that nation, John McAllister, opened the country’s first optical shop in 1783.4 After languishing for five years as a British prisoner of war—how fitting that the nation’s first optometrist was jailed fighting for independence—he established a whip and cane business in Philadelphia. Looking to add to the scope of his wears, he purchased a small collection of spectacles, “not enough to fill a stove pipe hat,” according to a family history written by his grandson.4 The spectacles sold well and McAllister set out to not only make corrective lenses, but—at the behest of his friend, Benjamin Franklin—provide vision care.5 While the venerated names of American revolutionaries survive, not so much as a plaque stands on the spot where optometry was born. However, this early image, preserved by the Library of Congress, captured McAllister’s son, John McAllister, Jr., leaving the shop on June 17, 1843.6

|

On several points, the article is incredibly relevant to today’s refractionist. “With only minor—very minor—modifications, it could sound like advice from today,” says Dr. Harris.

Losing Focus?

In a time when ocular disease and surgical care garner the lion’s share of attention, and autorefraction is a necessary tool to increase efficiency and patient convenience, has the profession lost focus on the art of refraction?

Some dilution was inevitable as the profession added new responsibilities, says Dr. Taub. “I think we saw a need to provide care, especially in rural areas, and filled the need. At some point, the health need seems to have pushed refractive care to the side.” He says that this took place even though optometrists, on average, spend at least half of their exam time on the refractive aspects of the visit.

“Even before students leave optometric education, there is a push to drop examination components that do not seem to serve a purpose,” says Dr. Taub. “Asking the patients or their families questions regarding school performance, birth history or social development gets thrown out the window.” And tests of binocular vision and accommodation are often cursory, he notes.

|

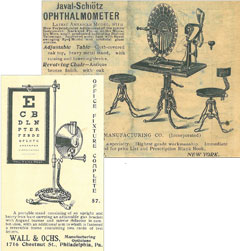

| A few Victorian-era ads from The Optical Journal. Above is the Javal-Schiøtz Ophthalmometer and an eye chart from Wall & Ochs opticians in Philadelphia. Click to enlarge. |

“We cannot blame this all on the commercialization of care,” Dr. Taub says. “I know plenty of caregivers at commercial locations that make wonderful referrals to our clinic while others at private offices rarely make such referrals.”

Dr. Harris says new technologies and the need to see more patients played a role in refraction falling by the wayside to the extent that it has. “Retinoscopy was a mainstay tool to establish our refractive starting position,” Dr. Harris says. “Then along came the autorefractor. It was an amazing application of autofocusing technology, which promised to reduce chair time and improve refractions, and it could be done by staff before the doctor ever even got into the room.”

Over time, though, he suggests, optometrists recognized the limitations of the autorefractor and are starting to shift back to emphasizing the role of the retinoscope. “With the return to using this valuable tool has come the additional insights derived from the brightness and color of the reflex and from the variations in both over time along with many other subtleties which have been documented over the years,” says Dr. Taub. “Is there a place for autorefractors? Yes, but the cases are fewer than we suspected.”

Mark Wilkinson, OD, of the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine, finds the timing ironic, as the shift comes in an era when 20/20 uncorrected vision after surgery is prized more than ever before. “The goal is emmetropia for patients after refractive surgery as well as cataract surgery, so it is critically important to know exactly what their refractive errors are before surgical intervention.”

Yet, he says many optometrists and ophthalmologists rely on technicians and/or autorefraction to do the job. “Autorefractors can help in many cases. That said, I think that I can do what an autorefractor can do as fast, or faster, and as or more accurately, with a retinoscope.”

“I think optometry has pushed itself to focus more on eye disease evaluation and management,” de-emphasizing refraction, says Dr. Wilkinson. “With optometry working to expand the level of care they can provide, for very good reasons, the time it took to learn these new skills took away from the time that was spent learning to be good refractionists,” says Dr. Wilkinson. Refraction, he says, “is and should continue to be a cornerstone of what optometry does.”

Optometrists are just now beginning to contend with a new model of vision testing—and of doing business—that could prove disruptive: online refractions.

This new concept in refractive eye care is more than just a direct threat to the livelihood of an optometrist. It represents a dispiriting denigration of vision testing, a once-proud tradition that requires keen intellect and careful attention. If online exams take off with the public, the quality and thoroughness of the refraction will be sacrificed in the rush to fill an Rx. What might the high-minded practitioners of the late 19th century think of the hasty and hurried refraction one can get today with a click of a mouse? “The spectacle peddlers are back,” perhaps.

|

1. Cox ME. Optometry, the Profession: Its Antecedents, Birth, and Development. Chilton Co., 1947. 2. Prentice C. A mteric system of numbering and measuring prisms. The Optical Journal. Jan 1891;1(1). 3. Cross J. Dynamic Skiascopy, or the controll of accommodation in estimating errors of ocular refraction with the retino-skiamter. The Optical Journal.1901. 4. Hill RL. Static and dynamic skiametry. The Optical Journal. 12 March 1914. |