Corneal epithelial regeneration is constantly taking place. The limbus houses the palisades of Vogt—a specialized niche for maintenance and development of corneal stem cells that differentiate to form the basal cells of the epithelium. From this region, the cells migrate centrally then move anteriorly, transforming into wing cells and then superficial squamous cells. The superficial cells desquamate and are taken away by the tear film.

Wound Healing Up Close

A corneal insult triggers a cascade of healing mechanisms. Epithelial injury stops basal cell mitosis and causes the release of cytokines and growth factors. Basal cells develop filopodia, which enable them to migrate across the wound. Adhesion molecules expressed by the basal cells allow for adherence to the underlying basement membrane. Once the defect is covered with a single basal cell layer, mitosis resumes and cells proliferate to re-establish regular epithelial stratification. Basal hemidesmosomes slowly re-form to replace the weaker adhesion molecule connections.

In cases of deeper stromal trauma, additional molecules are released, including prostaglandins, platelet-activating factors, cytokines and various growth factors.1 These substances potentiate transformation of keratocytes into myofibroblasts—contractile cells capable of migrating and filling the wound. The myofibroblasts arrange into a network, secrete extracellular matrix, then apoptose.2 Unfortunately, residual haze is common as a result of increased collagen fibril diameter and less precise organization.3

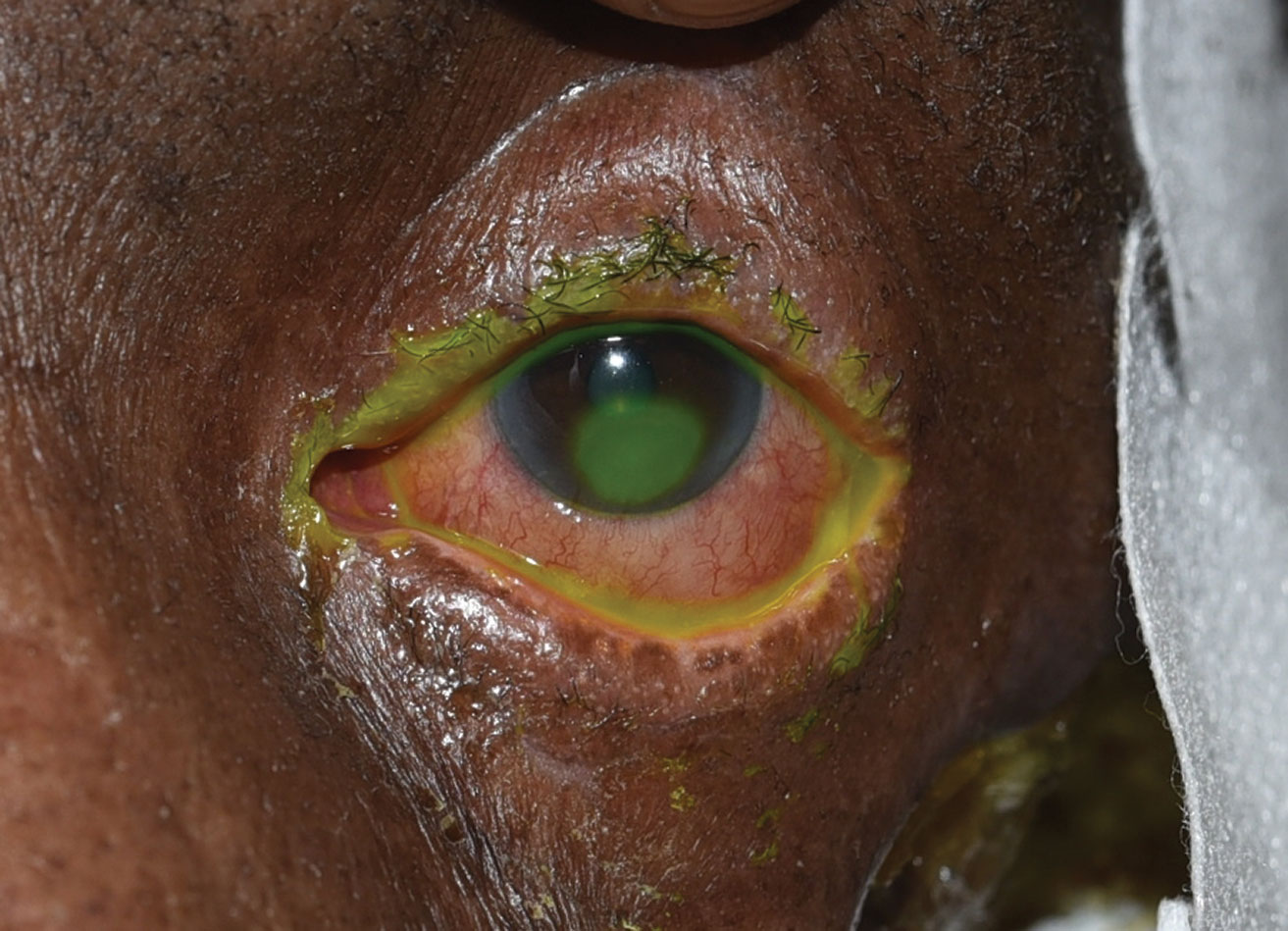

|

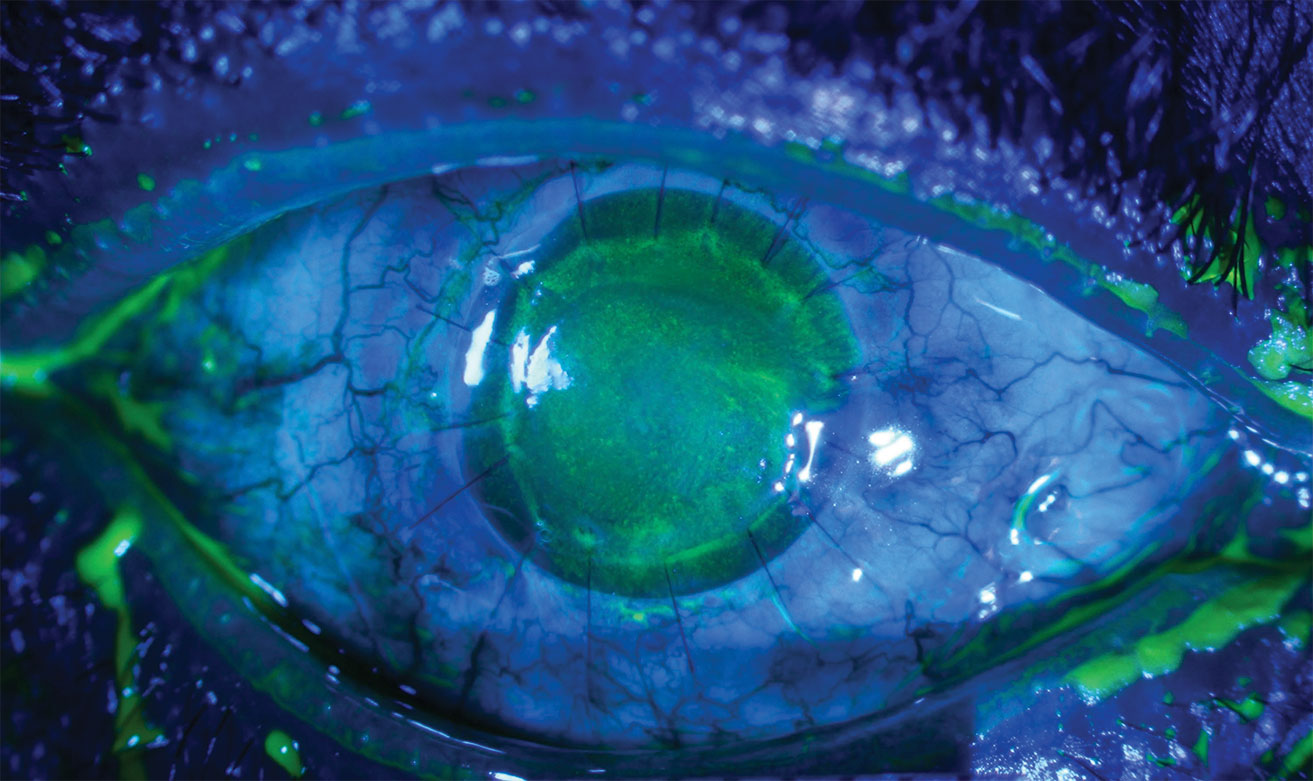

| This patient displays an inferior corneal epithelial defect seen in neurotrophic keratopathy. Click image to enlarge. |

Impaired Corneal Healing

The procedure described above, while elegant, is fallible. Several conditions can lead to the corneal healing process failing, forming persistent epithelial defects (PED) and possibly underlying ulceration.

Neurotrophic keratitis (NK), for example, compromises corneal healing by reducing nerve function.4 Diabetes, herpetic keratitis, corneal surgery, topical drug toxicity and trigeminal nerve damage are all among the leading causes of neurotrophic PEDs.4

Limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) is defined by inhibited proliferation of epithelial basal cells leading to conjunctivalization of the limbus and adjacent cornea. LSCD may result from chemical or thermal burns, topical drug toxicity, a history of ocular surgery, Stevens-Johnson syndrome or ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Additionally, severe autoimmune-related dry eye or cicatricial exposure of the ocular surface can result in poor epithelial health.4

Clinical Evaluation

A comprehensive approach that includes both history and slit lamp exam is integral to determine a PED’s etiology. Accurate history can aid in determining risk factors for poor corneal healing. Conditions such as diabetes, history of ocular or neurologic surgeries, contact lens wear or use of topical ophthalmic medications should all raise red flags.4

On clinical examination, perform a thorough inspection of the ocular adnexa, tarsal and bulbar conjunctiva, cornea and anterior chamber. In the ocular adnexa, don’t overlook eyelid malposition, as this can be a component of poor ocular surface health. Poor lid closure, entropion, ectropion and poor blink through lateral canthal tendon disinsertion may lead to exposure keratopathy. Examination should include the lid margin for signs of keratinization, meibomian gland dysfunction or trichiasis.

Next, turn your attention to the conjunctiva for signs of subepithelial tarsal fibrosis, symblepharon, bulbar conjunctival scarring or forniceal shortening. These may provide insight into a history of prior ocular surface inflammation/infections or prior ocular surgeries. Careful observation at the limbus can provide clues about LSCD, such as pannus or abnormal peripheral corneal epithelium.

On corneal examination, infectious etiologies such as a bacterial corneal ulcer or herpetic keratitis must be ruled out by noting pertinent negatives, which include absence of a stromal infiltrate, anterior chamber reaction or keratic precipitates. Consider the appearance of the corneal epithelial defect; neurotrophic corneal defects typically present as inferior ovoid epithelial defects with rolled edges. Photo documentation is quite helpful in many cases. You should assess decreased corneal sensation before making an NK diagnosis. This can be done quantitatively with Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometry or qualitatively with the “cotton wisp” test.

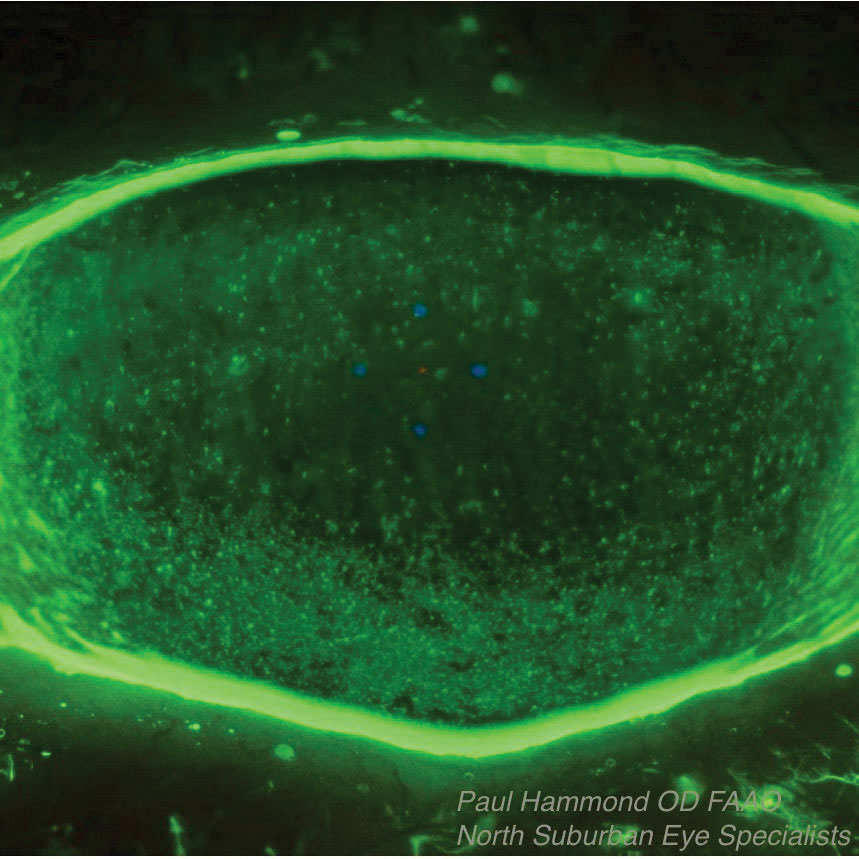

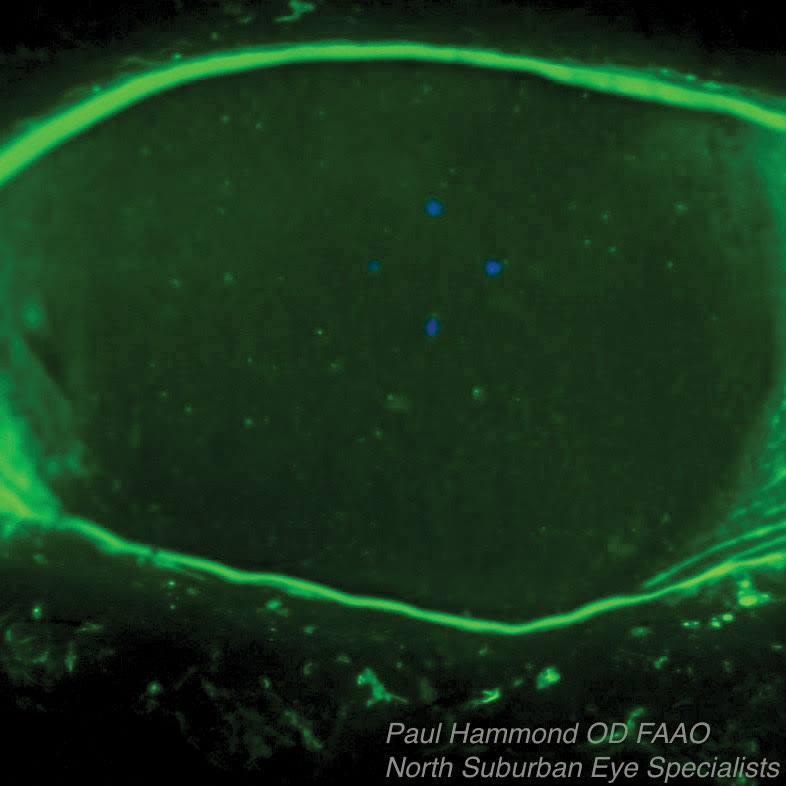

|

|

| This Sjögren’s syndrome patient’s associated dry eye was treated with Prokera, an overlay that protects the surface and releases nutrients and growth factors while absorbing inflammatory debris as the epithelium grows in underneath it. The top photo shows the patient before Prokera placement, the bottom one is after placement. |

A Graduated Approach

Corneal healing can often be aided by the placing an oxygen-permeable bandage contact lens with frequent preservative-free artificial tears and prophylactic antibiotic drops. In cases where inflammation is not a major factor, consider early placement of punctal plugs to augment natural tear retention.

In the event that an epithelial defect will not heal with basic treatment strategies, more aggressive therapies are indicated. Though scleral lenses may be considered at any stage of impaired ocular surface, severe or recalcitrant PEDs often require their use to protect the ocular surface. Patients with deep-set eyes, small lid apertures or poor dexterity may not be able to successfully use a scleral lens. Amniotic membrane tissue or autologous serum eye drops may be used when more conservative measures fail. In these cases, moving toward early tarsorrhaphy may be the best option.

Custom-fit Sclerals

For patients who are able to tolerate daily contact lens wear, scleral lenses can provide significant benefit in corneal healing.5 These devices serve as a physical barrier, decrease evaporation from the ocular surface, increase tear-cornea contact and provide a smoother refractive surface. In chronic NK or LSCD, they are a great first-line treatment strategy.

In the event that a cornea or sclera is quite irregular, consider fitting or referring for a more customizable device. Unlike most other scleral lens devices, the PROSE (Prosthetic Replacement of the Ocular Surface Ecosystem, BostonSight) employs a computer-aided design system to allow for more precise fitting. The EyePrintPro (Eyeprint Prosthetics) uses 3D scanning of a patient’s ocular surface impression to create a device that is precisely contoured to the individual eye.

The Serum Solution

ASEDs, also known as autologous serum tears, are becoming increasingly popular amongst eye care professionals. ASEDs contain numerous growth factors, immunoglobulins, fibronectin and vitamin A, which promote cell proliferation and migration.

The first step in producing ASEDs is a blood draw. After blood is harvested from an individual, it is then centrifuged and the serum portion is retained. Depending on the compounding pharmacy’s regulations or the doctor’s specifications, the percent of autologous serum may vary. Many pharmacies start at 20% serum, but this may be modified based on response to treatment. Traditionally, we have relied on local or hospital compounding pharmacies to produce ASEDs for our patients. More recently, companies such as Vital Tears, which provides a mobile phlebotomy service, allow for a convenient option for both the physician and patient.

Additional autologous hemoderived products include plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Both of these products are obtained in a similar fashion, and the difference in production occurs with the speed and duration of centrifugation. PRP and PRGF have proven advantages over ASEDs, due to their increased concentration of growth factors, anti-inflammatory cytokines and other platelet derivatives since they are not lost in the centrifugation process.4

Both PRGF and PRP have been successful in treating dry eye disease, post-LASIK ocular surface syndrome, and PRP specifically has also been used for glaucoma-associated ocular surface disease and recurrent corneal erosions.6-10 Experimental research may support reduced inflammation and likelihood of stromal scarring with PRP vs. ASEDs, though no prospective randomized clinical trials have compared the efficacy of these three hemoderived ophthalmic treatments.11

Allogeneic, as opposed to autologous, platelet-derived eye drops are also being evaluated in clinical studies. One such therapy, Elate Ocular (Cambium Medical) is seeking FDA approval for ocular graft vs. host-disease. FDA-approval could allow insurance coverage for this therapy in the future. These drops would alleviate the need for patient blood draws, as the platelets are sourced from healthy donors.

Typically, autologous eye drops are started four to six times daily in the affected eye, with the percent and dosage titrated upward according to clinical response. Each of the aforementioned autologous drops must be kept in the freezer until ready to be used, then stored in a fridge or on ice if the patient is traveling. This, along with the lack of insurance coverage, must be discussed with the patient prior to starting treatment. Unfortunately, these factors may sometimes be a deterrent for those who need this therapy.

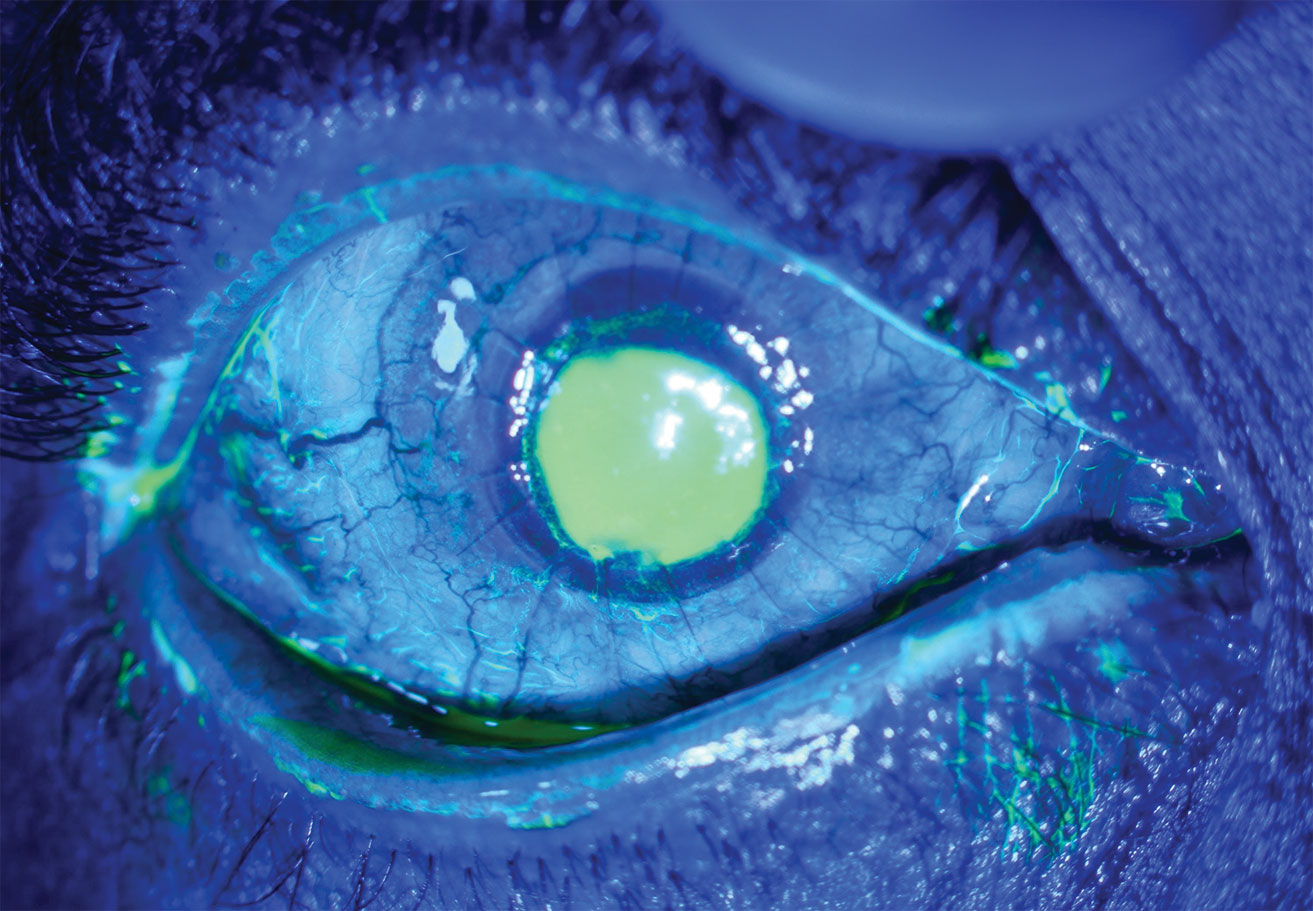

|

|

| This patient with neurotrophic keratitis underwent penetrating keratoplasty. Here, they’re seen before (top) and after (bottom) plasma rich in growth factor eye drop application. Click images to enlarge. |

Amniotic Options

Ocular surface grafting via amniotic membrane (AM) application has been reported in ophthalmic literature as far back as 1940, but has gained significant popularity in the last 20 years as cryopreserved and dehydrated products have become widely available for in-office use.12 The donor graft material is harvested from placental tissue obtained during elective Caesarean sections, screened for transmissible diseases and preserved. Prokera (Biotissue), a cryo-preserved product, is held in position by a polycarbonate ring. Two dehydrated options, AmbioDisk (Katena) and BioDOptix (Integra LifeSciences), are placed under a bandage contact lens.

AM provides many proven beneficial properties to accelerate ocular surface healing beyond acting as a physical barrier and reducing frictional microtrauma from the eyelids. These include anti-inflammatory, anti-scarring, antimicrobial and anti-angiogenic effects, as well as inherent limited immunogenicity.13 AM use can promote corneal nerve regeneration and increase corneal sensitivity, which supports corneal re-epithelialization.14,15

The most common conditions treated with AM include NK, ulcerative keratitis, filamentary keratitis, recurrent corneal erosions, refractory dry eye disease, acute chemical/thermal burns and LSCD.16 Cases of infectious keratitis have also been treated with AM, but only after appropriate antimicrobial treatment has had time to sufficiently sterilize the ulcer.17 The purpose of AM in these cases is to decrease inflammation, pain and scarring and promote epithelialization.

Starting to use amniotic membranes may seem daunting, but company representatives will help clinicians prepare the materials and instructions for your first patient. Our experiences have left us with two primary strategies for applying AM: as a bandage to protect the ocular surface while it regenerates or as scaffolding for the new growth itself. Prokera works well as an overlay, protecting the surface, releasing nutrients and growth factors, and absorbing inflammatory debris as the epithelium grows in underneath it. Conversely, AmbioDisk adheres directly to the corneal surface and can serve either as an overlay bandage or can be trimmed to inlay healthy basement membrane scaffolding for epithelial cells to adhere to and migrate across.18 The AM will ultimately integrate into the host tissue when used as an inlay, or slough off as an overlay when epithelial healing is complete.

The primary complication for Prokera is patient discomfort due to the polycarbonate ring, but in our experience, this is less common with the Prokera Slim and improves after the first 24 hours. The dehydrated AM products tend to have issues with adherence and may slip out from under the bandage lens. We’ve found this issue can be avoided by using a temporary hydrogel adhesive like ReSure Sealant (Ocular Therapeutix) around the periphery of the graft before placing the bandage contact lens.

The recent success of AM in treating the ocular surface has stimulated interest in amniotic-derived eye drops for similar indications, including Regener-Eyes (RNI Solutions) and Genesis (Ocular Science).19 These drops have many of the same cytokines, growth factors and nutrients as amniotic membrane grafts, and select case reports and retrospective series show they can improve corneal epithelial healing and limbal stem cell proliferation.20,21 Currently, the lack of standardized clinical trials leaves much to be learned about nuances and efficacy, but amniotic drops hold promise as topical biologic treatments for ocular surface disease while avoiding the blood draw process necessary for ASED/PRP/PRGF.

|

|

|

| Platelet-rich plasma can help repair recurrent corneal erosions. Here it is after centrifugation (top left), mixing with normal saline (top right) and, finally, bottled (bottom). |

Oral Medications

Tetracyclines exhibit anti-collagenase activity by reducing levels of matrix metalloproteinases and pro-inflammatory interleukins. Forthis reason, research shows they are beneficial in epithelial basal cell migration and stromal healing, and are commonly used in cases of stromal ulceration or severe chemical burns. Typically, doxycycline is dosed at 100mg twice daily. Though not a stand-alone therapy, tetracyclines may confer additional benefit in recalcitrant PEDs.

Oral antivirals are also an important consideration when a PED is not improving as expected. Underlying herpetic keratitis is a common culprit in these cases, and starting oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is a safe adjunctive medication to prescribe that may easily resolve the problem.

Lid Closure

One of our mentors once said, “a closed eye is a happy eye.” He was referring to how ambient air can desiccate the ocular surface in cases of severe dry eye, but it’s a mantra we can apply even with our neurotrophic patients. However, closure of the lids by surgical means can impact an individual’s psychosocial health due to altered cosmesis. That being said, it remains a viable option for PEDs that prove recalcitrant to other, more accepted means.

Tarsorrhaphies can be temporary or permanent. A great in-office option is a ‘tape tarsorrhaphy’—a very short-term approach that will allow for near total lid closure. This can be done by trimming a 1x1” square of plastic surgical tape, having the patient close their eyes, pulling their brow upwards to smooth any lid creases, then applying the tape with the inferior edge juxtaposing the eyelashes. It will likely need to be re-applied daily by the patient at home, and over the long term may cause a skin reaction underlying the tape.

Chemical tarsorrhaphy, performed by injecting botulinum toxin into the levator muscle, is an alternative that lasts approximately three months. Alternatively, a suture tarsorrhaphy may be done by select placement of sutures and bolsters through the upper and lower eyelids and may quickly be removed following resolution of the corneal defect. Permanent tarsorrhaphies employ excision of the lid margin epithelium prior to suturing, to allow the upper and lower eyelids to “stick” together once they heal, providing a longer term option for those with chronic disease.

Based on the severity of ocular surface disease, a permanent tarsorrhaphy may be performed and is typically closed up to the lateral limbus as a starting point.

New Drugs and Future Directions

It’s an exciting time in the eye care field, as new therapies are being developed to help us treat our patients. Oxervate (cenegermin-bkbj, Dompé Pharmaceuticals) is the only FDA-approved topical therapeutic drop indicated for NK. It contains cenergermin-bkbj, a recombinant form of human nerve growth factor that supports differentiation and maintenance of corneal nerves. Nexagon (Eyevance Pharmaceuticals)—the active ingredient is CODA001—is a topical drug that inhibits cell membrane hemichannel formation, decreasing proinflammatory cytokine release and tissue ischemia. Its primary indication is the treatment of PEDs, and clinical trials are underway as of this year.

Surgical treatment for NK has also gained popularity recently through a procedure called corneal neurotization, which involves adjoining a healthy sensory nerve graft from the contralateral supraorbital or supratrochlear nerve, and placing it into the peripheral cornea.22

Corneal healing is a complex process, and we need to be ready to step in when the body’s own mechanisms aren’t adequate. From treatment of simple epithelial abrasions to managing neurotrophic corneal disease, each of us will face cases when our clinical expertise will be called upon. With new advances in both medications and surgical options, we can rise to meet the challenge.

Dr. Bozung practices at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami.

Dr. Hammond is a consultative optometrist at North Suburban Eye Specialists in Minneapolis.

1. Jester J, Ho-Chang J. Modulation of cultured corneal keratocyte phenotype by growth factors/cytokines control in vitro contractility and extracellular matrix contraction. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77(5):581-92. 2. Myrna KE, Pot SA, Murphy CJ. Meet the corneal myofibroblast: the role of myofibroblast transformation in corneal wound healing and pathology. Vet Ophthalmol. 2009;12 Suppl 1:25-7. 3. Remingto, L. Cornea and Sclera. In: Clinical Anatomy of the Visual System. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier, 2012. 4. Alio J, Rodriguez A, Ferreira-oliveira R, et al. Treatment of dry eye disease with autologous platelet-rich plasma: a prospective, interventional, non-randomized study. Ophthalmol Ther. 2017;6(2):285-93. 5. Alio JL, Rodriguez AE, Abdelghany AA, et al. Autologous platelet-rich plasma eye drops for the treatment of post-LASIK chronic ocular surface syndrome. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:2457620. 6. Anitua E, Muruzabal F, De la fuente M, et al. Plasma rich in growth factors for the treatment of ocular surface diseases. Curr Eye Res. 2016;41(7):875-82. 7. Sánchez-avila RM, Merayo-lloves J, Fernández ML, et al. Plasma rich in growth factors eye drops to treat secondary ocular surface disorders in patients with glaucoma. Int Med Case Rep J. 2018;11:97-103. 8. Lee JH, Kim MJ, Ha SW, et al. Autologous platelet-rich plasma eye drops in the treatment of recurrent corneal erosions. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2016;30(2):101-7. 9. Anitua E, De la fuente M, Muruzabal F, et al. Plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) eye drops stimulates scarless regeneration compared to autologous serum in the ocular surface stromal fibroblasts. Exp Eye Res. 2015;135:118-26. 10. de Rotth A. Plastic repair of conjunctival defects with fetal membranes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 1990;83(3):522-5. 11. Nakamura T, Yoshitani M, Rigby H, et al. Sterilized, freeze-dried amniotic membrane: a useful substrate for ocular surface reconstruction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(1):93-9. 12. John T, Tighe S, Sheha H, et al. Corneal nerve regeneration after self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane in dry eye disease. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:6404918. 13. Morkin MI, Hamrah P. Efficacy of self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane for treatment of neuropathic corneal pain. Ocul Surf. 2018;16(1):132-8. 14. Cheng A, Zhao D, Chen R, et al. Accelerated restoration of ocular surface health in dry eye disease by self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(1):56-63. 15. Sheha H, Liang L, Li J, et al. Sutureless amniotic membrane transplantation for severe bacterial keratitis. Cornea. 2009; 28(10):1118–23. 16. Malhotra C, Jain AK. Human amniotic membrane transplantation: Different modalities of its use in ophthalmology. World J Transplant. 2014;24;4(2):111-21. 17. Murri M, Moshirfar M, Birdsong O, et al. Amniotic membrane extract and eye drops: a review of literature and clinical application. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1105-12. 18. Asl NS, Nejat F, Mohammadi P, et al. Amniotic membrane extract eye drop promotes limbal stem cell proliferation and corneal epithelium healing. Cell J. 2019;20(4):459-68. 19. Gupta PK. Clinical outcomes of amniotic cytokine extract in the treatment of dry eye disease. Presented at the 2017 American Academy of Ophthalmology Annual Meeting. 20. Terzis JK, Dryer MM, Bodner BI. Corneal neurotization: a novel solution to neurotrophic keratopathy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(1):112-20. |