Spring is in the air. But, the spring air is full of pollen, mold and other sources of allergenic proteinsnot a good thing for allergy sufferers.

The eye is essentially an open window that encounters a multitude of environmental substances, making it a prime site for allergic inflammation. Here, we will discuss the pathophysiology of ocular allergies and the four common manifestations.

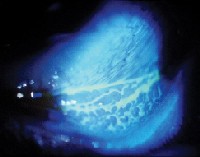

|

| Atopic keratoconjunctivitis is a type I ocular hypersensitivity reaction. Note the thickened eyelid margins and scaly, swollen lids. |

Pathophysiology

Ocular allergic disease results from a hypersensitive reaction that starts when an allergen becomes trapped in the tear film. Antigen presenting cells (APCs), which are located in the conjunctiva and the epithelial and subepithelial layers of the body, engulf the allergen, then migrate to a draining lymph node and deliver the allergen to CD4+ helper T cells. These cells then proliferate and become T helper type 2 (Th2) cells.

Next, the Th2 cells produce interleukin-4 (IL-4) and -13 (IL-13). These two cytokines cause B cell lymphocytes to produce immunoglobulin E (IgE), the antibody thats associated with allergy.1-4 (In non-allergic individuals, Th1 cells produce the cytokine interferon- gamma, which blocks the IgE production induced by IL-4 and IL-13.1,5,6)

The IgE then binds to the surface of the conjunctival mast cells, which store histamine in cytoplasmic granules. The mast cells degranulate, and the explosive release of histamine causes the immediate or early phase of an allergic reaction. (Eosinophils are not present in type I hypersensitivity acute phase reactions.)

Once released, histamine binds to receptors on vascular smooth

muscle, causing vasodilation (hyperemia, redness) and the formation of gaps between endothelial cells, resulting in vascular permeability. Fluid leaks out of the vessels into tissue (chemosis, tearing, lid swelling, rhinorrhea). Histamine binds to receptors on nerve endings, leading to pruritus (itching), the hallmarks of ocular allergy.1,4-6

Persistent signs and symptoms comprise a late-phase response, resulting from mediators released by the other cells, such as eosinophils. Eosinophils release major basic protein, a toxic product resulting in keratitis and shield ulcers associated with chronic allergic conditions.5

Two Common Allergies

The common allergies optometrists see in their offices are type I and/or type IV.

|

| A Type 1 allergic reaction (allergic conjunctivitis). |

Type I hypersensitivity reactions occur locally or systemically. The antigen (allergen), the activation of B-cell lymphocytes and the production of IgE characterize the response.7 Then, binding of the allergen to IgE on mast cells results in the release of pre-formed histamine and the synthesis of prostaglandins and leukotrienes.

|

| A Type IV allergic reaction (contact dermatitis). |

By being aware of the cellular and molecular basis of the allergic response and the common manifestations of ocular allergy, we can enable our allergic patients to explore, rather than deplore, this season of rebirth.

|

The Common Manifestations of Ocular Allergy Seasonal and Perennial Allergic Conjunctivitis (SAC, PAC)

Type of Hypersensitivity Reaction: Type I.

Cause(s): SAC is triggered by pollens. PAC is triggered by dust mite feces and animal dander.5,8,9 Prevalence: Both conditions are found in up to 98% of patients who have ocular allergies.9 Symptoms: A red, itchy and watery eye. Signs: Conjunctival chemosis and lid swelling. Rhinitis is an associated finding.5 Treatment: A combination antihistamine-mast cell stabilizer, cold compresses, tear substitutes to flush the allergen, and avoidance of the allergen. Topical corticosteroids are considered in severe or recalcitrant cases, but they should only be used for a short time given the potential side effects of cataract and increased intraocular pressure. However, Alrex, (loteprednol etabonate 0.2%, Bausch & Lomb) has been found to be safe for long-term use.10 Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis (VKC)

Type of Hypersensitivity Reaction: Type I and type IV.

Cause(s): Climate, sensitivity to individual-based allergen and genetic predisposition. Prevalence: Males younger than 10 years of age, especially those who live in warm climates and who have a family history of atopic disease.8,11 VKC usually decreases with puberty.5,8,12 Symptoms: Intense itching, foreign-body sensation, photophobia, tearing and stringy mucoid discharge. Signs: Papillae on the palpebral conjunctiva and possible limbal involvement with Trantas dots. Corneal involvement frequently occurs with the limbal form, but is more commonly associated with the palepbral form.5 Corneal involvement can lead to scarring and decreased visual acuity.5,8,11 Treatment: The same agents used to treat allergic conjunctivitis. Topical corticosteroids may also be warranted. Limited studies have reported the use of cyclosporine for VKC.5 Also, research is being done on adhesion molecule inhibitors to prevent eosinophil recruitment.6 A promising approach targets chemokine antagonismeotaxin 1 or chemokine receptor-3 (CCR3)to inhibit mast cell and eosinophil activity.9,13 Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) Allergic and Irritant Contact Dermatitis (ACD, ICD) of the Eyelid |

Dr. Wing is an associate professor at the Pennsylvania College of Optometry in Elkins Park, Pa.

1. Liu G, Deane-Myers A, Miyaki D, et al. Molecular and cellular aspects of allergic Conjunctivitis. In: Streilein JW, ed. Immune Response and the Eye. Chemical Immunology and Allergy. Vol. 73. Basel, Switzerland: Karger AG, 1999:39-58.

2. Matsuura N, Uchio E, Nakazawa M, et al. Predominance of infiltrating IL-4-producing T cells in conjunctiva of patients with allergic conjunctival disease. Curr Eye Res 2004 Oct-Nov;29(4-5):235-43.

3. Fujishima H, Shimazaki J, Takeuchi T, et al. Interleukin-4 and IgE in seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmologica 1996;210(6):325-8.

4. Abbas AK. Diseases of Immunity. In: Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2004:193-265.

5. Abelson MB, Smith L, Chapin M. Ocular allergic disease: Mechanisms, disease sub-types, treatment. The Ocular Surface; 2003;1(3):127-49.

6. Helinto M, Renkonen R, Tervo T, et al. Direct in-vivo monitoring of acute allergic reactions in human conjunctiva. J Immunol 2004 Mar 1;172(5):3235-42.

7. Gell PGH. Clinical aspects of immunology. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific, 1968:575-96.

8. Harry J, Misson G. Immunity, inflammation and infection. In: Harry J, Misson G. Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology. Oxford, England: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2002:30-113.

9. Ono SJ, Abelson MB. Allergic conjunctivitis: update on pathophysiology and prospects for future treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005 Jan;115(1):118-22.

10. Ilyas H, Slonim CB, Braswell GR, et al. Long-term safety of loteprednol etabonate 0.2% in the treatment of seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis. Eye Contact Lens 2004 Jan;30(1):10-3.

11. Bonini S, Coassin M, Aronni S, Lambiase A. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye 2004 Apr;18(4):345-51.

12. Zug KA, Palay DA, Rock B. Dermatologic diagnosis and treatment of itchy red eyelids. Surv Ophthalmol 1996 Jan-Feb;40(4):293-306.

13. Simons FE. Advances in H1-antihistamines. N Engl J Med 2004 Nov 18;351(21):2203-17.

14. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. Researchers explore mechanisms of allergic disease at 2005 AAAAI annual meeting in San Antonio. www.aaaai.org/media/news_releases/2005/03/032205.stm (24, March 2005).

15. Hogan D. Contact dermatitis, allergic. emedicine, www.emedicine.com/derm/topic84.htm (24 March, 2005).

16. Hogan D. Contact dermatitis, irritant. emedicine, www.emedicine.com/DERM/topic85.htm (24 March, 2005).