A 58-year-old African-American male presented to the clinic complaining of hazy vision in his left eye for three weeks. He was seen in urgent care two weeks prior and was diagnosed with an acute anterior uveitis in the left eye. He was prescribed 1% prednisolone acetate every two hours and 1% atropine twice daily.

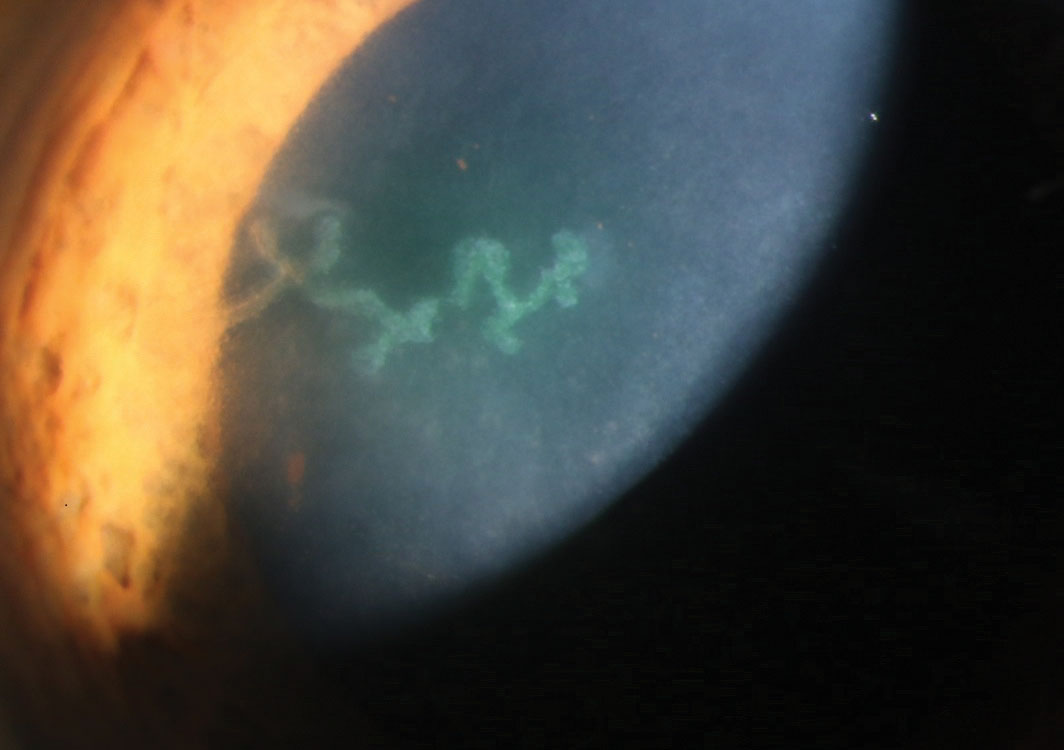

At presentation, his best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 OD and 20/40 OS. The left pupil was pharmacologically fixed, and there was no afferent pupillary defect seen in either eye. A slit lamp exam of the left eye revealed a dendritic corneal ulcer with central fluorescein staining and mild underlying anterior stromal edema without infiltration (Figure 1). The anterior chamber was deep and quiet. Iris was dilated and without atrophy. Corneal sensitivity was absent with cotton wisp in the left eye and present in the right. Preauricular nodes were not palpable. Dilated fundus exam and intraocular pressures (IOPs) were normal and equal.

We diagnosed him with herpes simplex epithelial keratitis (HEK) and prescribed him oral acyclovir 400mg five times a day for 10 days and explained that he needed to taper the prednisolone rapidly, starting QID for two days then decreasing by one drop every two days.

|

Fig. 1. This patient demonstrates active herpetic dendrite as seen using sodium fluorescein staining. |

Hazed and Confused

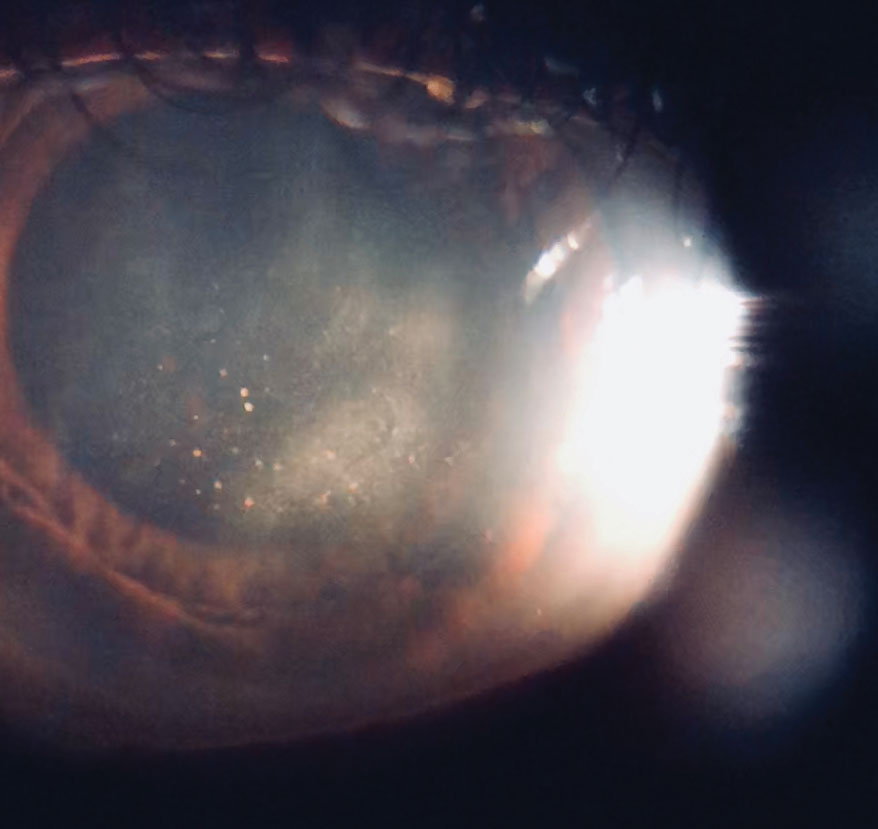

This patient was seen three times over the following two weeks. His epithelial defect closed and his vision improved to 20/25 with correction. The anterior chamber remained quiet after the prednisolone had been discontinued. One week after completing the oral acyclovir, the patient reported hazy vision in his left eye. His acuity was 20/25, but a slit lamp exam revealed a focal disciform area of stromal edema with bullae and underlying keratic precipitates localized to the area of swelling (Figure 2). No stromal neovascularization or infiltrate was noted.

The anterior chamber was quiet. IOP was normal and equal. On dilated examination, the vitreous and fundus were normal.

The diagnosis of herpes simplex endotheliitis was made, and the patient was restarted on topical 1% prednisolone acetate QID in the left eye and oral acyclovir 400mg five times a day for another 14 days, then BID after that.

The patient’s previous records noted two separate incidences of herpetic eye disease, a dendrite in 2010 and keratouveitis in 2011 with treatment the corneal findings resolved and BCVA returned to 20/20. Acyclovir was continued at prophylactic dosing 400mg BID.

|

| Fig. 2. Here the patient demonstrates disciform herpes endotheliitis. |

Discussion

For a patient to present with three distinct anterior segment manifestations of herpes simplex virus (HSV) in such a short period is atypical, but it makes for a great review of some of the different ways ocular HSV can present and is treated. For brevity, this discussion will only focus on some anterior segment conditions; however, it is imperative that clinicians perform a dilated fundus exam in any urgent case to rule out posterior involvement.

HSV is the most common infectious cause of blindness in the developed world.1 Risk factors for HSV activation or recurrence include stress, ultraviolet exposure, trauma, menstruation and illness.1,2 Herpetic eye disease (HED) is typically unilateral and recurrent in the same eye. Patients with history of atopy, immune-compromise or immunosuppression can present with bilateral or more recurrent herpetic disease.2

Ocular manifestations of HSV are typically presumptive and diagnoses are made on clinical exam.3 Most conditions likely represent a combination of viral activity and host immune response.1 Confirmatory tests exist but are typically not performed because they are costly, impractical or unreliable.2 Methods include cytology, culture or polymerase chain reaction of tissue scraping or AC paracentesis.4 Basic serology is of limited value as many are latently infected by HSV.1

Treatments are prescribed empirically based on clinical presentation.

Table 1. Suggested Treatment Guidelines4 | ||

| Condition | Antiviral | Topical Steroid |

| Dendritic Keratitis | Topical—therapeutic, then prophylactic for 7 days after ulcer healed Oral—therapeutic for 7-10 days | Contraindicated |

| Geographic Keratitis | Topical—therapeutic, then prophylactic for 7 days after ulcer healed Oral—enhanced therapeutic for 14-21 days | Contraindicated |

| Endotheliitis | Oral—therapeutic for 7-10 days, then prophylactic | 4-8x/day Taper as indicated |

| Iridocyclitis | Oral—therapeutic for 7-10 days, then prophylactic | 4-8x/day Taper as indicated |

Presentations

Herpes simplex uveitis. Acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is usually idiopathic and does not warrant diagnostic testing. HSV accounts for up to 10% of all AAU.1-3 Suspicion of HSV uveitis increases in the presence of iris stromal atrophy, elevated IOP, diffuse keratic precipitates (KP) or history of recurrent uveitis or other herpetic disease in the same eye.1,3 Hyphema can be present in up to 12% of cases, and corneal manifestations of HSV may precede or follow uveitis.2,5 Differential diagnosis for HSV uveitis includes other causes of uveitis, including sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHI), Possner-Schlossman syndrome (PSS) and cytomegalovirus (CMV).1,2

Herpes simplex epithelial keratitis. HEK accounts for up to two-thirds of HED and presents as an ulceration whose center stains with sodium fluorescein and edges with rose bengal.6,7 Depending on the time of presentation, ulcers can be punctate, linear, dendritic or geographic.6 Ulceration is exacerbated by steroid use. HEK resolves on its own in 25% of cases, but can leave scarring, corneal hypoesthesia or both.6,7 Differentials for HEK can include neurotrophic or other infectious ulcers.

Herpes simplex endotheliitis. This form can present as a focal or diffuse area of stromal edema with KPs underlying the area. Mild anterior chamber reaction, elevated IOP, or both, may be present or absent.4,7 Studies and epidemiology on this specific condition are limited, as it has been included as a subset of herpes stromal keratitis (HSK) in the past though is now considered a distinct entity.4,8 Differentials for HSV endotheliitis include CMV endotheliitis, FHI and PSS.

Treatment

The goal of therapy is to preserve vision, alleviate pain and prevent morbidity (Table 1). Both topical and oral antivirals are available, and the choice between topical and oral is determined on a case-by-case basis.

The safety profile of oral acyclovir and valacyclovir is excellent—they are well tolerated long-term and are listed as pregnancy category B.4,7 However, adjusted dosing is necessary for patients with renal disease.4,7 Topical 1% trifluridine can cause corneal toxicity, and treatment should not exceed 21 days. Topical Zirgan (0.15% ganciclovir gel, Bausch + Lomb) does not show similar toxicity as trifluridine, but long-term studies are limited.4 While oral agents demonstrate good corneal penetration and therapeutic aqueous humor levels, available topicals do not. Topical 3% acyclovir ointment shows good penetration and aqueous levels, but is not available in the United States.4,9 So far, no evidence suggests combined topical and oral antiviral treatment is superior to a single treatment method alone.4,9

Table 2. Topical Dosing | ||

| Trifluridine 1% solution | Ganciclovir 0.15% gel | |

| Prophylactic | 5x/day | 3x/day |

| Therapeutic | 9x/day | 5x/day |

HEK can be treated with topical antivirals (Table 2). Oral antivirals are technically off label for HEK, but research shows therapeutic oral dosing is equivalent to topical treatment (Table 3).6 For geographic ulcers, enhanced therapeutic dosages are indicated.4

Adding epithelial debridement with antiviral treatment is not superior to antiviral alone, according to the literature.6 Debridement with placement of an amniotic membrane may be an alternative when antivirals are contraindicated or compliance is poor.10

For HSV iridocyclitis, or any keratitis other than HEK, oral antivirals are preferred over topical for superior penetration and long-term use. Start them before initiating steroids.4,7

The Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) suggests that therapeutic oral antiviral dosing, when added to topical steroid regimen, might be beneficial for treating HSV iridocyclitis, though the study sample was small.9,11 With endotheliitis, therapeutic dosing and topical steroids are recommended.12 For both conditions, steroids are tapered slowly over a month or longer to avoid rebound inflammation.3,4

Table 3. Oral Dosing | ||||

| Acyclovir |

Valacyclovir | Famciclovir | ||

| Prophylactic | 400mg BID | 500mg QD | 250mg BID | |

| Therapeutic |

400mg 3-5x/day |

500mg BID | 250mg BID | |

| Enhanced therapeutic |

800mg 5x/day | 1g TID | 500mg BID | |

Cycloplegics aid to prevent iris synechiae.1,4 Topical hypotensives can control elevated IOP, but IOP responds well to steroid and antiviral treatment in HSV uveitis and endotheliitis as apposed to FHI or CMV keratouveitis.3

Prophylactic antiviral dosing should be used for all conditions needing steroids even after completing the therapeutic regimen to prevent other conditions from blossoming.4 Long-term oral prophylaxis is recommended for patients with recurrent disease or high risk for vision loss. The HEDS group noted significant reduction in recurrence rates while on 12-month prophylactic acyclovir, especially those with a history of HSK. However, there was no improvement in recurrence rates after 12-month prophylactic therapy was completed, which suggests indefinite prophylaxis is necessary for some patients.4,9,13

Herpes can present in the eye in a variety of ways, and those outlined here only scratch the surface. In the above case, it is quite likely the patient’s uveitis was due to HSV, which then bloomed into a dendrite while he was on topical steroids without antivirals. There was nothing from his previous note to suggest his uveitis required antivirals at initial presentation, so close follow up was important to catch his HSV. The rapid taper of the steroids was initiated out of concern for exacerbating the dendrite but may have induced his conversion to endotheliitis. It may have been better to reduce, not discontinue, the steroid for several weeks to prevent such rebound.

Thankfully, with close follow up and appropriate treatment adjustments, the eye returned to normal and the patient was happy. For now, he will remain on prophylactic oral antivirals, perhaps indefinitely, as he has shown multiple recurrences in the past.

Dr. Schaeffer is a resident optometrist at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine in Miami.

Dr. Townsend is the optometric residency director at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine.

1. Gaynor B, Margolis T, Cunnigham E. Advances in diagnosis and management of herpetic uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2000;40(2):85-109. 2. Tabbara KF, Chavis PS. Herpes simplex anterior uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1998;38(4):137-47. 3. Siverio C, Imai Y, Cunningham E. Diagnosis and management of herpetic anterior uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2002;42(1):43-48. 4. White ML, Chodosh J. Herpes simplex virus keratitis: a treatment guideline. Hoskins Centers Compendium of Evidence-Based Eye Care. www.aao.org/clinical-statement/herpes-simplex-virus-keratitis-treatment-guideline. 2014. Accessed April 4, 2018. 5. Wilhelmus K, Falcon M, Jones B. Herpetic iridocyclitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1991;4(3):143-50. 6. Guess S, Stone D, Chodosh J. Evidence-based treatment of herpes simplex virus keratitis: a systematic review. Ocul Surf. 2007;5(3):240-50. 7. Tsatsos M, MacGregor C, Athanasiadis I, et al. Herpes simplex virus keratitis: an update of the pathogenesis and current treatment with oral and topical antiviral agents. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;44(9):824-37. 8. Prepose J. Herpes simplex keratitis: role of viral infection versus immune response. Surv Ophthalmol. 1991;35:345-52. 9. Sudesh S, Laibson P. The impact of the herpetic eye disease studies on the management of herpes simplex virus ocular infections. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1999;10:230-3. 10. Sheha H, Tighe S, Cheng A, Tseng S. A stepping stone in treating dendritic keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;Case Reports 7:55-8. 11. A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for iridocyclitis caused by herpes simplex virus. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Arch Ophthal. 1996;114:1065-72. 12. Porter S, Patterson A. A comparison of local and systemic acyclovir in the management of herpetic disciform keratitis. Bri J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:283-5. 13. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. New Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):300-6. |