|

Neuromuscular junction (NMJ) disorders result from destruction, malfunction or absence of one or more key proteins involved in neuromuscular transmission. The most common pathology is antibody-mediated damage or down regulation of ion channels or receptors, resulting in myasthenia gravis (MG), Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome and acquired neuromyotonia (Isaac’s syndrome).4 These three conditions share many common features. Then, there are congenital myasthenic syndromes, which are caused by mutations in neuromuscular junction proteins.

The most common and most important NMJ disorder, particularly for optometrists, is MG.

Myasthenia Gravis

MG most commonly affects young adult women and older men. These patients often present with characteristic fluctuating muscle deficits and fatigue.1,2

| |

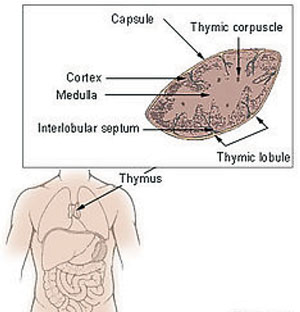

| The Thymus in MG The importance of T-cells in the pathogenesis of MG is increasingly apparent. The thymus is the central organ in T-cell mediated immunity, and abnormalities such as thymic hyperplasia or thymoma are well recognized in myasthenic patients. Most patients with MG have either thymic hyperplasia (70%) or thymoma (10-15%).5 Photo: National Cancer Institute. |

The prevalence of MG in the United States has risen over the past two decades to an estimated 14 to 20 per 100,000.3 However, MG remains under-diagnosed and the prevalence is probably higher. MG can be divided into ocular and generalized forms. Among patients presenting with ocular symptoms only, 20% to 50% remain ocular, while the remaining patients will progress to generalized disease.5 For those with ocular MG, there is no reliable way to predict progression to generalized MG. However, if MG remains ocular for one year, the progression rate is 16% and drops to 6% if the disease remains localized for three years.5

Diagnostic Challenges

Diagnosing MG can be difficult because the disease may mimic almost any pupil-sparing pattern of ocular misalignment. The fluctuating nature of MG can also create diagnostic confusion. Diagnostic testing for fatigue is not part of the routine ophthalmic exam, so you often have to think of MG before you can find it; added to that, not all patients who are dealing with fatigue have MG, and not all MG patients clearly fatigue.

Testing

Although no test for MG is 100% sensitive or specific, the ice pack test is simple, fast and relatively helpful.3 Other clinical signs to look for include orbicularis weakness, Osher’s “peek sign,” and Cogan’s lid twitch.4 Tests you should consider ordering include:

• Thyroid studies. Thymic abnormalities are associated with MG, but the nature of the association is uncertain. The thymus contains all the necessary elements for the pathogenesis of MG: myoid cells that express the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antigen, antigen-presenting cells and immunocompetent T-cells. MG patients with thymoma usually have more severe disease and electromyographic abnormalities, and higher levels of AChR antibodies than those without thymoma.

Approximately 10% of MG patients have a thymoma, while early-onset disease (before the age of 40) is associated with thymic hyperplasia. A CT thorax scan is mandatory in all anti-AChR antibody positive patients.1-3,6 Thyroid studies should always be obtained because of the concomitant presence of thyroid dysfunction in up to 13% of patients with MG.5

Table 1. Systemic Therapy3,6,7

|

• The Tensilon (edrophonium) test. This test has been largely superceded by the anti-AChR antibody assay in the diagnosis of MG, although it is still useful when the diagnosis needs to be confirmed with urgency.6 Note that the test carries a small, but not insignificant, risk of respiratory arrest and cardiac arrhythmias and should be used with caution in patients with a history of these conditions.

• Anti-AChR antibody assay. Because the positive predictive value of this test is extremely high, a positive anti-AChR antibody titer in a patient with fatigue and weakness is enough to confirm an MG diagnosis. However, the negative predictive value is low; thus, a negative assay does not rule out myasthenia gravis.5

About 50% of patients with purely ocular signs of MG, and 15% of those with generalized disease, do not have antibodies against the AChR.6 In the remainder of patients, practitioners must rely on clinical symptoms, signs and the results of detailed neurophysiology.6

• Neurophysiological studies. Repetitive nerve stimulation involves supra-maximal stimulation at 3Hz of a peripheral nerve (often the ulnar nerve), and recording the compound motor action potential from the relevant muscle. A decrement of more than 10% over five responses is considered consistent with MG.6 Unfortunately, the test is unreliable if the limb is cold or if the patient has taken anticholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors, and it is often normal in patients with ocular myasthenia.

• Single fiber electromyography. SFEMG is a more sensitive test where recordings are made from two muscle fibers in a single motor unit. Increased variability in the interval between paired action potentials, termed jitter, or occasional blocking of one of the potentials is considered evidence of a defect in neuromuscular transmission.6 However, because increased jitter can be found in conditions other than MG, it needs to be carefully interpreted.

| |

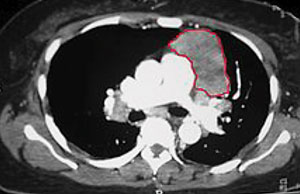

| Thymoma identified on a chest CT. Photo: Kurukumbi M, et al. |

Treatment Strategies

MG is one of the most treatable neurologic disorders, even though no clear consensus exists on treatment strategies (Table 1). Consider factors such as severity, distribution and rapidity of disease progression. Pharmacologic therapy includes AChE medication and immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclosporine, plasmapheresis and intravenous immune globulin.6

A thymoma should be removed because of the risk of metastatic spread, although this will not result in disease remission. Consult a cardiothoracic surgeon whenever discussing thymectomy.3,7,8

In patients with persistent ptosis, eyelid taping or a ptosis crutch may be beneficial. For patients who remain diplopic even after medical treatment, prism or occlusion therapy is a viable option. Strabismus surgery may be effective in patients whose deviation is too large to correct with prism and who show no change for up to 12 months.5

| Click here to read "See You at the (Neuromuscular) Junction: Part 1." |

Myasthenia gravis is a chronic disease that may worsen acutely over days or weeks. Proper optometric management requires scheduled re-evaluation, a close doctor-patient relationship, and close follow-up care cordinationed with primary care and neurology.

1. Miller NR, Newman NJ. The essential clinical neuroophthalmology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999.2. Benatar M. A systematic review of diagnostic studies in myasthenia gravis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16(7):459-67.

3. Keesey JC. Clinical evaluation and management of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2004:29(4):484-505.

4. Ajamian P, ed. Drag and Droop. Review of Optometry. 2015;152(10):32.

5. Vaphiades MS, Bhatti MT, Lesser RL. Ocular myasthenia gravis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2012;23:537-42.

6. Hill M. The Neuromuscular Junction Disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74.

7. Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(10):1023-36.

8. Saperstein DS, Barohn RJ. Management of myasthenia gravis. Semin Neurol. 2004;24(1):41-8.