|

Studies estimate more than 30 million patients suffer from dry eye disease (DED) in the United States alone, but less than one million are receiving medical treatment.1,2 This is a huge population—estimated to be more than 10 times that of other common conditions such as glaucoma—in need of awareness, diagnosis and treatment.3 Most patients believe dry eyes and contact lens discomfort are normal parts of aging and don’t mention them to their doctors. This disconnect may leave millions of patients untreated or left to progress to advanced levels before they begin treatment, making it difficult and frustrating to manage.

In mid-July, the FDA finally approved a new drug for the treatment of signs and symptoms of DED: Xiidra (lifitegrast ophthalmic solution 5%, Shire Pharmaceuticals). It is the first in a new class of drugs known as lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) antagonists.

Welcome Xiidra

Xiidra is a preservative-free solution of lifitegrast 5% ophthalmic solution that comes in individual vials and is dosed BID.

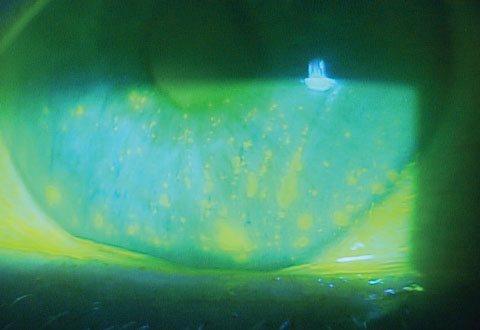

The drug went though four separate multicenter, prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-masked FDA clinical trials involving more than 1,000 subjects ranging in age from 19 to 97 with a predominance of female patients, at about 75%.4 Both the active drug and placebo were administered BID for 84 days, and safety and efficacy were determined between the groups. The study results revealed that the groups using Xiidra had a statistically significant clinical improvement in signs (corneal staining) and symptoms (eye dryness) compared with placebo. In the OPUS-3 study on symptoms of eye dryness, which involved 355 patients on Xiidra and 356 on placebo, Xiidra had a highly statistical improvement compared with placebo at day 84 (p=0.0007), day 42 (p<0.0001) and at 14 days after initiating therapy (p<0.0001).

|

| A new treatment option for DED could mean more patients find relief. |

For each study, patients were excluded who had: contraindications or hypersensitivity to the investigational product; previous lifitegrast treatment use; a disorder causing immunodeficiency; history of LASIK or similar surgery within 12 months; topical ophthalmic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent use; topical ophthalmic cyclosporine and systemic steroid use; and those who were pregnant or nursing.

During the one-year safety study, however, after day 14, study participants were allowed to use artificial tears (≤4 times daily, as needed), contact lenses (daily disposable lenses only), topical ophthalmic/nasal antihistamines/mast cell stabilizers and steroids (loteprednol only).

Top 5 Questions on Using Xiidra in PracticeQ: How quickly does Xiidra’s clinical efficacy manifest? Q: What criteria should we use to gauge successful response to therapy? A: You should first see improvement in osmolarity, then early symptoms and signs—but it depends on the severity of DED. Patients with milder DED will see symptoms improve sooner than patients with more severe dry eye disease. Q: Should a treatment-naïve patient be started on Xiidra instead of over-the-counter artificial tears? Q: If a patient is maintained well on Restasis, would there be any benefit from switching the patient to Xiidra? Q: Is there a potential synergistic effect with Restasis that might suggest a benefit of dual therapy? |

Safety was based on ocular and nonocular treatment-emergent adverse events. Adverse events were assessed for severity (mild, moderate, severe) and relation to the investigational drug (not related, possibly related, probably related). The most common (>5%) ocular finding associated with Xiidra was burning, and the most common (>5%) nonocular finding was dysgeusia, or a change in taste sensation. Most adverse events were reported as being mild to moderate in severity and transient.

Mechanism of Action

Studies have associated DED with inflammation involving the conjunctiva and lacrimal glands, and the mechanism of this process is becoming better known through more recent research.5,6 When the tear film is altered or hyperosmolar tears are present, the ocular surface over-expresses a ligand known as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1).7 These fingerlike projections on the epithelium and endothelium have binding sites for T-lymphocytes. The specific binding occurs via the LFA-1 integrin. LFA-1 is on the migrating T-lymphocyte and binds to ICAM-1. The interaction of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 is not only important for T-cell adhesion, but also migration, proliferation and cytokine release at sites of inflammation such as the conjunctiva or lacrimal glands.8-11 Once LFA-1 binds to ICAM-1, recruitment takes place, allowing the T-lymphocyte to enter. An antigen-presenting cell with the same binding mechanism activates the inflammatory cascade, resulting in release of cytokines and further expression of ICAM-1.12 Given this cascade of inflammation in dry eye patients, LFA-1/ICAM-1 blocking is a logical target for treatment.

Specifically, lifitegrast is a small molecule integrin antagonist that blocks binding of ICAM-1 to LFA-1 on the T-cell surface, inhibiting T-cell recruitment and activation associated with DED inflammation.13-15

Clinical Application

I was involved in three separate lifitegrast studies, and I still have DED patients who return regularly stating that their eyes felt better while in the study than at any other time. Given the rapid onset of effect (14 days is more rapid than any other drug studied to date for DED) and good safety profile, I expect this medication will further aid in treating the more than 30 million DED sufferers still in need of diagnosis and treatment.

Once we have access to this new therapeutic agent, we will better understand how to use Xiidra in the treatment of signs and symptoms of dry eye disease.

Why Xiidra?

DED is the most common disease optometry will manage—now and in the foreseeable future. A new therapeutic agent in our armamentarium is extremely valuable and exciting. Xiidra’s FDA approval and subsequent marketing will increase the awareness of dry eye as a significant, debilitating, chronic and progressive disease. With a better understanding of dry eye, more patients will present to doctors who will be prepared to use advanced diagnostics, such as osmolarity testing, to make the diagnosis. Finally, it will provide us with another therapeutic option for patients suffering from DED that involves the key inflammatory mechanisms. We will have access to a drug designed to effectively manage the signs and symptoms of dry eye that has a rapid onset and a good safety profile.

Dr. Karpecki is a consultant/advisor to Shire Pharmaceuticals, TearLab, Allergan and Bausch + Lomb.

|

1. Paulsen AJ, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, et al. Dry eye in the beaver dam offspring study: prevalence, risk factors, and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Apr;157(4):799-806. 2. Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Incidence of dry eye in an older population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 Mar;122(3):369-73. 3. Gupta P, Zhao D, Guallar E, et al. Prevalence of Glaucoma in the United States: The 2005-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(6):2577-85. 4. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new medication for dry eye disease. www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm510720.htm. 5. Carsons S. A review and update of Sjogren’s syndrome: manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:S433-43. 6. Pflugfelder SC, Huang AJW, Schuchovski PT, et al. Conjunctival cytological features of primary Sjogren syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:985-91. 7. Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13:227-42. 8. Ali H, Haribabu B, Richardson RM, Snyderman R. Mechanisms of inflammation and leukocyte activa-tion. The Medical Clinics of North America. 1997;81:1-28. 9. Springer TA. Traffic signals on endothelium for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration. Annual Review of Physiology. 1995;57:827-72. 10. Shimizu Y. LFA-1: more than just T cell Velcro. Nature Immunology. 2003;4:1052-4. 11. Gao J, Morgan G, Tieu D, et al. ICAM-1 expression predisposes ocular tissues to immune-based inflammation in dry eye patients and Sjogrens syndrome-like MRL/lpr mice. Experimental Eye Research. 2004;78:823-35. 12. Stern ME, Gao J, Schwalb TA, et al. Conjunctival T-cell subpopulations in Sjogren’s and non-Sjogren’s patients with dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2609-14. 13. Murphy CJ, Bentley E, Miller PE, et al. The pharmacologic assessment of a novel lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 antagonist (SAR 1118) for the treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca in dogs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3174-80. 14. Sun Y, Zhang R, Gadek TR, et al. Corneal inflammation is inhibited by the LFA-1 antagonist, lifitegrast (SAR 1118). J Ocular Pharmacol. 2013;29:395-402. 15. Zhong M, Gadek TR, Bui M, et al. Discovery and development of potent LFA-1/ICAM-1 antagonist SAR 1118 as an ophthalmic solution for treating dry eye. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2012;3:203-6. |