|

A 26-year-old Hispanic female, from the Dominican Republic, presented with a 12-year history of decreased vision in the right eye. She said the vision loss was painless and progressive. Other than the early decreased vision, her ocular and medical histories were unremarkable.

Her best-corrected visual acuities were counting fingers in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. Her pupils were equal and round and, although her left eye was reactive, her right had a sluggish response to light. We noted a strong afferent pupillary defect in the right eye. Ocular motility was full in both eyes. Confrontation visual fields were constricted in all fields in the right eye and full to finger counting in the left eye. Intraocular pressures were 15mm Hg OD and 13mm Hg OS. The patient had a 15 prism diopter constant exotropia of the right eye.

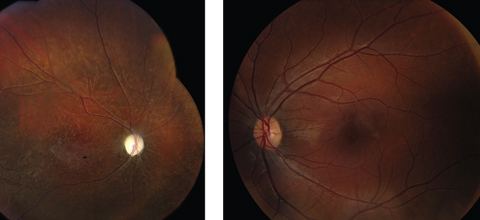

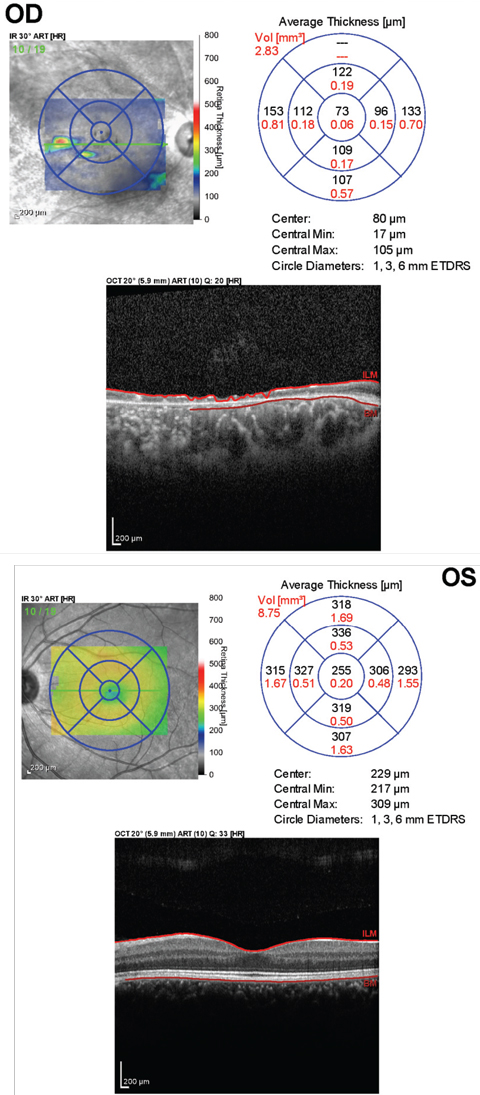

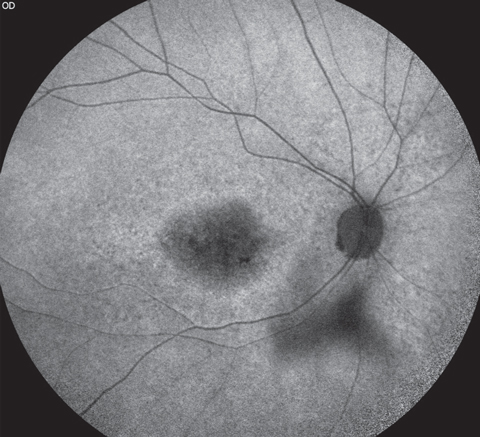

An anterior segment examination was unremarkable. Dilated fundus examination of the right eye revealed significant findings (Figure 1). A dilated fundus examination of the left eye revealed clear vitreous and a healthy optic nerve, macula and peripheral retina. An optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan of the macula was taken, as were fundus autofluorescence images (Figures 2 and 3).

|

| Fig. 1. Fundus photo of the right eye (at left) during the late stage with optic atrophy, retinal arterial narrowing and degenerative changes in the retina. The left eye appears normal. Click image to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. How would you describe the optic nerve?

a. Diffuse pallor.

b. Optic atrophy.

c. Advanced cupping.

d. Disc swelling.

2. What is the most likely diagnosis?

a. Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa.

b. Presumes ocular histoplasmosis.

c. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis.

d. Post-traumatic chorioretinopathy.

3. What additional test would be helpful to confirm the diagnosis in the acute setting of this condition?

a. Fluorescein angiography.

b. Electroretinogram.

c. SD-OCT.

d. All of the above.

4. What is the most likely etiology?

a. Genetic mutation.

b. Nematode.

c. Trauma.

d. Fungus.

5. In which patients does this

condition typically occur in?

a. Elderly.

b. Children.

c. Young adults.

d. B and C.

For answers, see below.

|

| Fig. 2. This OCT of the macula of the right eye (above) shows severe atrophy of both inner and outer retina. The OCT of macula of the left shows a normal foveal contour. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

We noted extensive optic atrophy in the patient’s right eye in addition to a narrowing of the retinal arteries and pigmentary changes throughout the retina of that eye. The left eye was completely normal.

Given the patient’s demographics, history of vision loss occurring at a young age and the appearance of the fundus, we diagnosised her with diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis (DUSN). The patient presented to the clinic in the late stage of the disease, limiting treatment to observation.

Discussion

DUSN, originally termed “unilateral wipe out syndrome,” is a progressive ocular infection caused by various types of nematodes.1 The most common nematodes that induces DUSN are Ancylostom caninum, Baylisascaris procyonis and Toxocara canis.2 Infection results in persistent inflammation and degenerative changes in the retina. It typically occurs in otherwise healthy children and young adults with no significant ocular history. It usually affects only one eye, but a few bilateral cases have been reported.3 It can lead to severe visual impairment and is a cause of blindness in children, especially in tropical areas, including the southeastern United States, the Caribbean and parts of South America. Additionally, cases have been reported in parts of Europe.3

Clinical presentation is divided into two stages, early and late. The early, or acute, phase of DUSN is characterized by loss of central vision, vitritis, vasculitis, optic nerve swelling and recurrent crops of evanescent, multifocal, white-yellow lesions at the level of the outer retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).4 Left untreated, the late phase of this condition results in severe vision loss, typically 20/200 or worse.1 Findings in the late stage include optic atrophy (with subsequent afferent pupillary defect), narrowing of the retinal arteries and marked focal and diffuse degenerative changes in the retina and RPE.2 Rarely, choroidal neovascularization can occur.

The mechanism of dysfunction in this condition may involve a local toxic effect on the outer retina by the nematode itself, as well as a diffuse inflammatory and toxic reaction affecting both the inner and outer retina.1 Definitive diagnosis is made by actual visualization of the nematode in the subretinal space. This only occurs in about 25% to 30% of patients.3 Differential diagnoses in cases where the worm is not visualized include retinal sarcoidosis, syphilic chorioretinitis, toxoplasmosis, presumed ocular histoplasmosis, multifocal posterior placoid pigment epitheliopathy and multiple evanescent white dot syndrome in the early stage.3

In the late stage, differentials include retinitis pigmentosa, post-traumatic chorioretinopathy and occlusive vascular disease.3

|

| Fig. 3. This fundus autofluorescence of the right eye shows areas of hypofluorescence corresponding to the areas of RPE atrophy seen clinically. |

Monitoring and Treatment

Fluorescein angiography can be useful in the early stages of DUSN. It can reveal hypofluorescence of the retinal lesions followed by late staining.1 Leakage can be seen around the optic disc. Serologic testing, stool examinations and peripheral blood smears are of little value in diagnosing DUSN.2 Electroretinography (ERG) can also be performed in these patients. Most patients with DUSN have an abnormal ERG, even when tested early in the disease course.2 Changes commonly seen in the ERG are a decrease in rod and cone function, with a B-wave being more affected than the A-wave.4 OCT may also be useful in assessing patients with DUSN. It is common to find a decrease in the retinal nerve fiber layer as well as the central macular thickness.4 Disruptions of both the inner and outer retinal layers can be observed. Additionally, it may be useful to help identify the location of the worm.

When visible, treatment of choice is the eradication of the parasite with laser photocoagulation.1 The worm is usually found near the retinal lesions. In patients where it cannot be identified, high-dose oral anti-helminthic therapy, such as albendazole, is recommended. Oral corticosteroids may help decrease the inflammatory response. Researchers also believe that laser photocoagulation adjacent to the retinal lesions may aid in ocular penetration of albendazole by disrupting the blood-retina barrier.3 Some improvement in visual acuity is expected in these patients following laser photocoagulation. In cases presenting during the late stage of this disease, vision loss is irreversible and does not improve with medical or surgical treatments.

Our patient was made aware of the diagnosis. Unfortunately, she would not benefit from any treatment as damage to the retina and optic nerve has already occurred and cannot be recovered. We did recommend that she take monocular precautions and stressed the importance of wearing protective eyewear.

Dr. Diamantakos is a resident at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.

1. Gass JD, Braunstein RA. Further observations concerning the diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983 Nov;101(11):1689-97. |

Retina Quiz Answers:

1) b; 2) c; 3) d; 4) b; 5) d.