|

A 67-year-old Hispanic female presented with complaints of long-standing bilateral central visual field loss. She reported being diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) nine years prior and receiving laser retinal treatment in each eye. Her health history was positive for Paget’s disease and Type 2 diabetes.

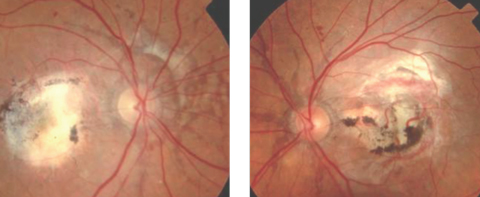

Best-corrected visual acuities were 20/200 OD and 20/400 OS, both using eccentric viewing. Given her health history, we were unsurprised that dilated funduscopy revealed bilateral angioid streaks, moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy and laser treatment scars in each eye. No drusen or other signs of AMD were evident (Figure 1).

This clinical picture led us to believe our patient did not have AMD; instead, she most likely developed choroidal neovascularization (CNV) associated with the contamination of Bruch’s membrane that occurs with angioid streaks. She was referred to a low vision rehabilitation clinic, where she achieved success using various optical and non-optical devices.

|

| Fig. 1. This patient has angioid streaks that radiate from the optic disc, in addition to macular laser scarring and blot hemes. Click image to enlarge. |

A Streaky Past

This patient provides a classic example of angioid streaks—structural defects linked to several systemic conditions, the frequency of which increases with age. They occur at the level of Bruch’s membrane, lying beneath normal retinal blood vessels, and typically present as bilateral deep red or grayish lines with irregularly serrated edges.1

When you see angioid streaks as a clinical sign, it’s time to take a closer look at the patient’s detailed history and review of systems, and conduct a thorough ophthalmic and, in most cases, systemic workup to determine the underlying cause.

Table 1. Common Systemic Conditions Associated with Angioid Streaks

|

Clinical Picture

Angioid streaks intercommunicate in a ring-like pattern around the optic disc in approximately 30% of cases and radiate outward from the disc in 70% of cases.1,2 The streaks come to an abrupt end and seldom extend past the equator. Additional posterior segment findings in eyes with angioid streaks may include a peau d’orange or leopard-skin spotting that consists of speckled, yellowish mottling of the posterior pole, most apparent in the temporal aspect of the macula.

Peripapillary chorioretinal atrophy, focal peripheral chorioretinal scars, optic nerve head drusen and reticular pigment dystrophy of the macula may also be found in association with angioid streaks. In the event of blunt trauma, eyes with angioid streaks may be more likely to suffer vision loss due to the existing break in Bruch’s membrane.1,2

Patients with angioid streaks are strongly advised to wear polycarbonate eyeglasses to protect against traumatic retinal damage. Because eyes with angioid streaks will always be at risk for CNV due to the damage to Bruch’s membrane, they should have eye exams at regular intervals.

CNV in the peripapillary and macular regions can occur in a small percentage of patients with angioid streaks, leading to severe vision loss.3 The visual prognosis, if untreated, is poor, and most traditional treatment modalities have failed to limit the devastating impact on central vision. However, research shows novel treatment with anti-VEGF agents may yield favorable results.1,4,5 The researchers also found early treatment and extended follow up were critical to therapeutic success.5 To help detect CNV early, clinicians should perform optical coherence tomography in addition to dilated funduscopy at each follow up visit.1

|

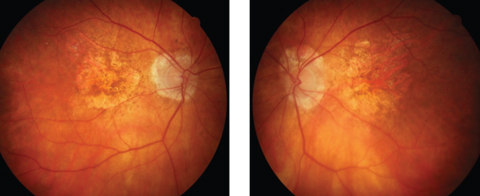

| Fig. 2. Advanced atrophic AMD may masquerade as angioid streaks. Click image to enlarge. |

Systemic Involvement

While angioid streaks should raise suspicion of a serious underlying systemic condition, the patient’s whole clinical picture will help you uncover the exact etiology (Table 1).

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is an inherited connective tissue disorder. It affects elastin fibrils in the skin’s dermis layer, and appears as yellow papules known as “chicken skin.” PXE may cause changes in arterial walls, the heart, gastrointestinal tract and Bruch’s membrane, causing mineralization and deposition of phosphorus. Cardiovascular findings in PXE may include hypertension due to atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease and mitral incompetence. Neurological findings may include cerebrovascular accident, intracranial aneurysms and cerebral ischemia.5

Of patients with PXE, 85% develop ocular involvement, referred to as Grönblad–Strandberg syndrome.6 In addition to angioid streaks, the literature reports other fundus lesions, including optic disc drusen, macular pattern dystrophy, crystalline bodies and midperipheral “comet-tail” atrophic spots.6

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is a disease of collagen resulting from a deficiency of hydroxylysine. Patients may develop dermatologic, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and respiratory signs and symptoms. Ocular complications include epicanthal folds, keratoconus, high myopia, retinal breaks and detachment, ectopia lentis, blue sclera and angioid streaks.1

Paget’s disease, our patient’s diagnosis, is a chronic, progressive condition whose key clinical feature is bone deformity. It may become evident as an enlargement of the skull, deafness and malformation of long bones. Angioid streaks and optic atrophy are the main ocular manifestations.7

|

| Fig. 3. CNV and subretinal hemorrhage in an eye with past trauma. |

Hemoglobinopathies occasionally associated with angioid streaks include homozygous sickle cell disease, sickle cell trait, sickle cell thalassemia, sickle cell hemoglobin, hemoglobin H, homozygous B-thalassemia major, intermedia and minor, and hereditary spherocytosis. The frequency of angioid streaks in the hemoglobinopathies increases with age, with a rate of occurrence of approximately 1.5% in younger patients and 22% in patients 55 and older.1,8,9

Other systemic conditions that may be associated with angioid streaks include acromegaly, dwarfism, diabetes mellitus, idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura and acquired homolytic anemia. Researchers have also reported cases of angioid streaks in patients with lead poisoning.1,9

After an extensive workup with negative findings for common systemic associations, some patients may be diagnosed with idiopathic angioid streaks.

|

| Fig. 4. Traumatic choroidal rupture may also injure Bruch’s membrane, leading to CNV. Click image to enlarge. |

Masqueraders

Clinicians should always be on the lookout for conditions that can mimic angioid streaks. Among the most common are exudative and advanced atrophic AMD, choroidal rupture, toxoplasmosis, choroidal sclerosis, myopic lacquer cracks, histoplasmosis, retinal vasculitis and papillitis and traumatic retinal hemorrhage with or without CNV (Figures 2-4).1

Angioid streaks, resulting from damage to the elastic lamina of Bruch’s membrane, are often harbingers of systemic conditions and warrant immediate attention by eye care providers. Early diagnosis is vital to minimize functional vision loss due to any resulting CNV or trauma.

1. Abusamak M, Abdelal OM, Kharouf I, Hamdan SM. Improving differential diagnosis of angioid streaks: diagnostic considerations and a case study. Retinal Physician. November 1, 2011. www.retinalphysician.com/issues/2011/nov-dec/improving-differential-diagnosis-of-angioid-streak. Accessed December 5, 2017. |