|

|

|

|

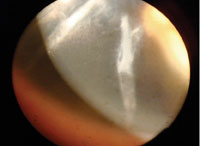

A gaping corneal RK incision.

|

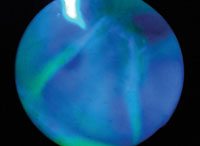

Incision taking up fluorescein.

|

Closure of gaping incisions using sutures.

|

Radial keratotomy (RK), a popular procedure in the 1980s and early 1990s for the correction of low to moderate myopia (-1D to -6D) and astigmatism, seems primitive by today’s exacting standards. It primarily involved creating partial-thickness incisions through approximately 90% of the cornea in a radial pattern around the mid periphery, to flatten the central cornea while steepening the periphery.

Short-term complications of RK included pain, infection, delayed healing, poor scotopic vision due to radial corneal scars, epithelial ingrowth and neovascularization of incisions, corneal erosions, epithelial defects, gaping or non-healing incisions, micropunctures of Descemet’s membrane, corneal perforation and endothelial cell loss. Because RK was relatively imprecise and more risky than PRK and LASIK, it fell out of favor relatively soon after the advent of laser-based procedures.

Undoing the Damage

RK’s long-term complications were never well studied before it became popular, and were largely unknown. Although most patients enjoyed relatively stable vision for years, an alarmingly high number continued to experience progressive corneal flattening as they aged, leading to significant hyperopia and irregular astigmatism.

Daily fluctuating vision—due to diurnal intraocular pressure changes causing the cornea to change shape—was a common complication experienced by RK patients.

Splitting or gaping incisions are a less common complication that we still see decades later. The patient may notice a sudden onset of corneal pain or decreased vision, but can also present with mild or no symptoms. Surgical closure of these incisions is often warranted to improve anterior corneal shape, decrease risk of epithelial ingrowth, and to prevent neovascularization and permanent corneal warpage.

Gaping incision closure is typically done with non-dissolving nylon sutures. Partial corneal-depth sutures are used to close the wound, and then the knots are buried under the epithelium. Excessive tension is needed to ensure permanent wound closure; this often induces local steepening of the cornea that can temporarily reduce vision and persists until the sutures are removed at a later date.

Postoperatively, patients need to be monitored for infection, leaking suture sites and excessive inflammation that could precipitate further corneal scarring. Patients should also be counseled that while the sutures are inducing asymmetric tension to their cornea, the vision is likely to change. Sutures can be left in the cornea for months or years, until the surgeon feels comfortable that there is little risk of re-splitting the incisions upon removal. If sutures are left in for a long period of time, patients should be monitored for suture erosion and possible related GPC.

This procedure can temporarily make vision worse, but patients should be counseled that the long-term medical risks from not closing the incisions can be more serious than the possible (and often temporary) vision changes.