As our understanding of glaucoma evolves, the risk factors we associate with the disease change with it. A risk factor such as intraocular pressure was at first thought to be an integral part of glaucoma, then was de-emphasized, and is now once again considered a strong predictor of risk. New risk factors, such as central corneal thickness, have surfaced. And some suspected risk factors, such as diabetes, do not appear to be risks for glaucoma at all.

In this article, Ill draw on information from three large studies published in recent years. These studies have clarified and redefined the importance of many risk factors we consider for glaucoma:

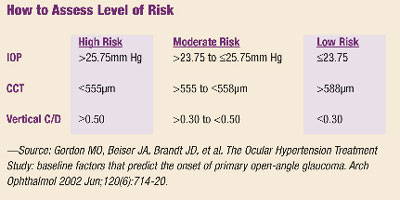

- The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) found that central corneal thickness, as well as age, cup-to-disc ratio, pattern standard deviation on visual field, and intraocular pressure are good predictors for glaucoma development.1

- The Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial (EMGT) reaffirmed that high IOP is a significant risk factor for glaucoma progression.2

- The Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study (CNTGS) indicated that reducing IOP, even in patients with normal-tension glaucoma, can reduce the progression of glaucoma.3

With that in mind, lets look at the usualand the unusualrisk factors themselves.

|

Intraocular Pressure

Not long ago, glaucoma researchers and clinicians downplayed the role of intraocular pressure as a risk factor, even to the extent of defining glaucoma without mention of IOP. More recently, studies have confirmed that IOP is an integral risk factor in glaucoma, even for patients with normal-tension glaucoma. Glaucoma is once again generally regarded as a pressure-related disease, and now we have the studies to prove it.

In OHTS, elevated IOP was confirmed to be an important and independent risk factor for development of glaucomatous damage measured by field loss or nerve damage. (The median untreated baseline was almost 25mm Hg.) Lowering the IOP by 20% and to a level below 24mm Hg decreased the risk of progression from 9.5% to 4.4% over an average follow-up time of five years.4 Thats a decrease of risk of progression of about 58%.

High IOP isnt a risk factor only in pressure-dependent glaucoma. The CNTGS demonstrated that even in patients with normal-tension glaucoma, pressure is still a factor. The researchers in this study reduced pressure by 30% from baseline.5 After correcting for the negative impact caused by cataracts, they found that relative risk of vision loss due to normal-tension glaucoma was reduced from 35% to 12%.

In patients with diagnosed open-angle glaucoma, the EMGT found that for every 1mm increase in IOP from the initial baseline examination, the risk of progression increased by as much as 13%.2

By the same token, the EMGT quantified the benefit that glaucoma patients can achieve when they lower IOP. Specifically, every 1mm reduction in IOP reduces the relative risk of progression by 10%. In other words, if you lower the IOP in a patient from 20mm Hg to 17mm Hg, you reduce the patients risk for glaucoma progression by roughly 30%.

Central Corneal Thickness

One of the most surprising findings of the OHTS study is the apparent impact of central corneal thickness on the risk of glaucoma. In OHTS, the risk of developing glaucoma was highest among participants with the thinnest central corneal measurements within all IOP groups and the entire range of baseline vertical C/D ratios.1 In this study, central corneal thickness is clearly an important risk factor for development of damage, and is independent of other risk factors.

The authors of the OHTS reports state, We conclude that central corneal thickness provides new information about the risk of developing POAG, and we recommend its measurement in the clinical evaluation of patients with ocular hypertension.1

Interestingly, the EMGT did not find that central corneal thickness was a significant risk factor for progression. Numerous explanations may exist for the discrepancy in conclusions, including different population bases, different manner of statistical analysis used, etc. Note that the EMGT included a population almost exclusively of whites and was less than one-fifth the size of OHTS.

|

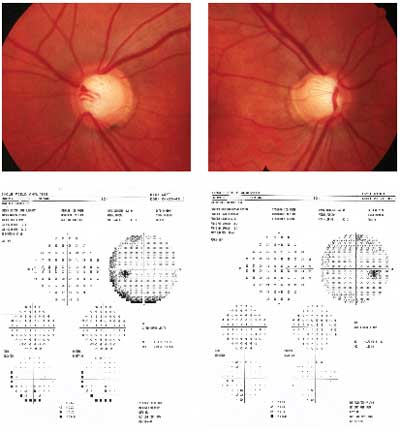

| This patient has high IOPs and a positive family history of glaucoma, but normal visual fields. Would these risk factors justify initiating treatment for glaucoma? |

Bottom line: Does central corneal thickness really matter? Definitely.

The follow-up question then becomes: How precisely must we correct for corneal thickness when measuring IOP? If youre more comfortable with calculating an adjusted measurement, thats fine. But bear in mind that conversion tables that use CCT to calculate real IOP will still only give you an estimate. Thats due to at least a few reasons. For one, pressure is a slippery value and it changes during the course of the day. Also, the conversion tables arent all in agreement, and it appears that CCT is not related to IOP in a linear fashion. Lastly, even our gold standard of measurement, Goldmann tonometry, has a margin of error of about 10%.

Cup-to-Disc Ratio

Some doctors might argue that a large cup-to-disc ratio is already evidence of glaucomatous damage, not really a risk factor. But OHTS did include cup-to-disc ratio as a risk factor, reasoning that a baseline examination provides no clue whether a patients C/D is stable or has enlarged due to glaucoma.

The study found that patients with larger C/D ratios, even those unaffected by glaucoma (i.e., no evidence of focal notching, disc hemorrhage or pallor), may be at greater risk for developing glaucoma.1 Both vertical and horizontal C/D ratios proved to be significant risk factors for progression to glaucoma, though the vertical C/D ratio was a slightly better predictor.

Age

Older age is an independent risk factor for development of glaucomatous damage, both OHTS and EMGT indicate. Neither study defines older age, but suggests merely that, as one ages, the likelihood for glaucoma increases.

However, this is something of a two-sided coin. The studies looked at risk of glaucomatous progression over a five-year period. That is, with all other factors being equal, an older patient has a greater risk of progression in the next five years than a younger patient. But keep in mind that younger patients can expect to have more years ahead of them, so they may have a higher accumulative risk over their lifetimes.

We must always consider the benefits and risks of treatment against the risks of symptomatic loss of vision affecting quality of life within a patients expected lifetime. Therefore, given two patients of different ages with the same findings, many clinicians tend to be more aggressive in managing elevated intraocular pressure in the younger patient in the belief that there is a greater accumulative risk in future years. Thus, older age may have statistical strength as a risk factor, but may be a less important factor in terms of management given a particular patient.

Race

- Blacks. Many population-based studies have shown that people of African descent have an increased risk of developing glaucoma when compared to whites. In OHTS, for instance, African-American race was associated with a 59% increase in the risk of developing glaucoma.1

But theres more to the story. In multivariate risk analysis, blacks tended to have two additional risk factors: thinner central corneal thickness and larger C/D ratios. When you weigh in these two factors, the issue of race evaporates. In other words, blacks do appear to be at increased risk for glaucoma, but thats because they more often have thinner corneas and larger C/D ratios than whites. - Hispanics. While OHTS did not have a large enough sample size of Hispanics to provide a definitive analysis, the study results were consistent with other research that found a higher prevalence of POAG in Hispanic subjects. As a recent comparison, the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study found that the rate of open-angle glaucoma among Latinos was higher than in whites, and similar to that in blacks.6

- Asians. Again, OHTS provides no analysis for this subset of patients. However, separate studies report a higher prevalence of normal-tension glaucoma among Japanese subjects, which could be considered for other Asians as well.7

Family History

Family history of glaucoma is a well-established risk factor for primary open-angle glaucoma, OHTS says. But its findings, and that of EMGT, dont bear that out.

In OHTS, about 42% of the study participants reported a relative with glaucoma. Yet those who reported a family history that went on to develop POAG (8.5%) were statistically the same as those who did not report a family history but developed POAG (7.3%). The EMGT study also evaluated the role of family history and found it plays a relatively insignificant role.

Does that mean we disregard family history as a factor? While family history may not be as important from a statistical analysis standpoint as some believe, it may be very important from an emotional standpoint in dealing with the patient. Consider the 65-year-old white male with five siblings with glaucoma, or the borderline suspect who reports that her mother went blind from glaucoma. If such a factor is important to the patient, then it must be important to me in the patients management.

Visual Field

Greater pattern standard deviation in baseline visual fields did prove to be a positive risk factor for development in OHTS. However, the OHTS investigators had to perform four baseline visual field tests to generate this standard deviation number to determine that its a risk factor. So, it is unlikely that pattern standard deviation will prove to be a useful risk factor in the analysis of these patients.1

In the EMGT, which looked at patients with early glaucomatous damage, greater mean deviation on baseline visual field was a positive risk factor for progression during the course of this study.2 Put another way, the greater the damage the patient had in the beginning of the study, the more likely the patient was to have progression.

Other Positive Risk Factors

- Exfoliation. EMGT recognized pseudoexfoliation (presence of exfoliative material) as a major risk factor, not for presence of disease, but for progression of disease. Bear in mind that this study included participants with POAG, exfoliative glaucoma and normal-tension glaucoma. This particular issue was not included in OHTS.

- Disc hemorrhage. The presence of a disc hemorrhage during the course of the study also proved to be a risk factor for progression in EMGT and CNTGS. Many clinicians would say disc hemorrhage is evidence of damage, not a risk. Still, these studies point out that a hemorrhage increases the risk of field loss getting worse.

Negligible Risk Factors

Some of the biggest surprises that came out of OHTS were that conditions we believed to be risk factors were not.

- Myopia. While other studies have shown myopia to be an apparent risk factor for development of glaucoma, this was not found in the OHTS study. Participants in this study were limited to no more than -6.00D of myopia, so myopia beyond this level may still be an issue. The EMGT also showed refractive error to be a non-issue.

- Diabetes. OHTS showed that not only is diabetes not a risk factor, but it may even play a protective role. (See The Diabetes Factor below.)

Systemic Medical Factors

Many clinicians consider a glaucoma suspects general medical health to be an important issue, but this is difficult to prove based upon the OHTS and EMGT studies. The baseline factors that were found to present no added risk in the EMGT are:2

- Gender.

- High or low blood pressure.

- Cardiovascular disease.

- Migraine or Raynauds phenomenon.

- Smoker (current or prior).

| The Diabetes Factor To the surprise of many, OHTS revealed that diabetes did not prove to be a risk factor for glaucoma. Indeed, those participants with diabetes developed glaucoma at a lesser rate (3%) than those participants without diabetes (8%).1 In other words, diabetes proved to be a protective factor against the development of glaucoma. This contradicts other studies that have shown diabetes to be either a risk factor for glaucoma or to have no impact on risk. Keep in mind that patients with diabetic retinopathy were not included in OHTS, so we should restrict our conclusions from this study to those diabetics without diabetic retinopathy. |

Both OHTS and EMGT have similar lists of risk factors found to be insignificant. These include: use of oral beta-blockers or oral calcium channel blockers, migraine, diabetes mellitis, high blood pressure, low blood pressure, heart disease and cerebrovascular accident.

CNTGS, however, showed that migraine patients who have normal-tension glaucoma tend to have a higher risk of progression.3

Because our understanding of glaucoma is always increasing, the risk factors described here by no means make a definitive list. There are many other potential risk factors that continue to surface in other studies. For example, sleep apnea has been identified as a potential risk factor, and cholesterol-lowering statin drugs have been linked to a decreased risk for glaucoma. These and some other potential risk factors will need additional prospective randomized review studies. Clearly, while we know a lot more than we used to about the risk factors, theres still a lot of work yet to be done.

Dr. Wooldridge is the clinical director of The Eye Foundation of Utah, an optometric co-management center in Salt Lake City, and is currently the education director for the Mountain West Council of Optometrists.

- Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002 Jun;120(6):714-20.

- Leske MC, Heijl A, Hussein M, et al.; Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group. Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: the early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003 Jan;121(1):48-56.

- Drance S, Anderson DR, Schulzer M; Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Risk factors for progression of visual field abnormalities in normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001 Jun;131(6):699-708.

- Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002 Jun;120(6):701-13.

- Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. The effectiveness of intraocular pressure reduction in the treatment of normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1998 Oct;126(4):498-505.

- Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Francis BA, et al.; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2004 Aug;111(8):1439-48.

- Shiose Y, Kitazawa Y, Tsukahara S, et al. Epidemiology of glaucoma in Japana nationwide glaucoma survey. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1991;35(2):133-55.