Youre sure to face this mystery in the contact lens portion of your practice: How does a patient with no prior history of ocular allergy or dry eye go from successful contact lens wear to mild discomfort to dropoutall in a relatively short time? And, how can you prevent this downward spiral? Good Tears and Bad Tears By Milton M. Hom, O.D. and Peter Simmons, Ph.D. Inflammatory Factors We believe that both schools of thought are correct, depending on the patient. Under the first scenario, inflammation may be 80% of the problem and the contact lens 20%. The second scenario may have an approximate breakdown of 80% contact lens and 20% inflammation. Inflammation is both a cause and a consequence of dry eyes. Powers of Deduction

Some say the seed for this kind of situation is sown well before you ever fit the patient with contact lenses. Sometimes, no matter how carefully you screen a patient, problems dont occur until the patient has worn contact lenses, says John Rinehart, O.D., of Peoria, Ariz. With the introduction of contact lenses, its one more element that can push allergies or dry eye over the edge. This can happen with a new wearer, and it can happen in patients who have been wearing lenses for a while.

If either of the above patients were new fits, the y would likely attribute their troubles to their new lenses. For this reason alone, early detection is key.

Unfortunately, patients tend to perceive these problems as contact lens-related, putting them at risk for dropout. For this reason, timely diagnosis and treatment are critical.

Back to the Beginning

Recent research has shed new light on the role of tears in contact lens-related dryness. Most notably, we are now focusing on the composition and quality of the tear film. A simple way of looking at tears is to divide them into two types: good tears and bad tears. Good tears are normal tears. Normal tears protect the eyes from infection, maintain a pristine cornea and conjunctiva, and supply an optically near-perfect refracting surface. Normal tears also keep a contact lens hydrated and clear of debris. Optimal contact lens performance is difficult to achieve unless tears are normal.

Bad tears are not normal. Instead, they have an imbalance of components. The classical tear model was a film consisting of three layers: lipid (or oil), aqueous and mucin. The new tear model has two layers: the lipid layer and aqueous gel layer. The latter is a combination of the mucin and aqueous layers, with a gradient of mucin concentration: more at the base and gradually less nearer the surface. These tear film layers consist of various types of oils (in the lipid layer), and many types of dissolved substances in the aqueous gel, including proteins, electrolytes and other organic compounds. Causes of imbalance include insufficient tear production from the lacrimal gland (tear-deficient causes of dry eye) and contaminated meibum from the meibomian gland (evaporative causes).

One imbalance in tears that is presently receiving much attention is the presence of inflammation. When inflammation is present in the eye, the tears bear much of the burden. Inflammatory cells such as t-cells are present. The t-cells produce cytokines, which in turn produce more t-cells, and the cycle continues. An inflamed eye will have large amounts of cytokines present in the tears. Cytokines induce ocular surface damage and disrupt the lacrimal gland feedback between the eye and the brain. The tears become bad.

Recent studies have shown inflammatory factors related to dryness. Chronic contact lens problems and irritation have a strong link to inflammatory processes. There are two schools of thought here.

One school of thought: The eye is prone to dryness from a contact lens because of an underlying inflammatory process, in which the lacrimal gland already has marginal tear production. This may be due, for example, to a drop in supporting androgen levels resulting from age or disease. The inflamed lacrimal gland produces a bad tear that is not conducive to contact lens wear, although symptoms are generally not present without lens wear.

When a contact lens is placed on the eye, the bad tear becomes stressed, and symptoms of dryness result. This concept is supported by animal models of dry eye that indicate that exposure to hypertonic saline and an air draft induces expression of inflammatory cytokines on the ocular surface (Luo et al., ARVO 2003).

Another school of thought is that the contact lens is a trigger for inflammation. The tears may be marginal, but not due to inflammatory causes. Once a contact lens is placed on the eye, it stresses the cornea due to the marginal tear film. Inflammation results in bad tears, and the patient feels dryness. This concept is supported by data indicating accumulation of pro-inflammatory compounds in the tears of contact lens patients (Albietz, CLAO 2001).

Unfortunately, there is no simple test to demonstrate if the tears have become bad, such as a practical assay for cytokines or other markers of inflammation. So, you will have to use judgment and deduction to determine the inflammatory status of your patients tears.

One hallmark sign of inflammation is redness. If the eye appears injected, inflammation is probably present. Inflammation can also be detected by deduction. For example, if you have tried altering the lens material or design or even the care solution without a change in symptoms, suspect an underlying inflammatory condition triggered by lens wear. Similarly, if the patient experiences dry eye discomfort under certain conditions (e.g., strong air conditioning or dry air) even without lens wear, he or she has a marginal tear film to begin with and may have an underlying inflammatory state.

If a patient has all normal tear test results and experiences no symptoms in the absence of a lens, then you should suspect the lens as the culprit, Youll need to change lens type or care system. Rewetting drops may be indicated.

Good tears are necessary for successful contact lens wear. Unfortunately, many patients tears may turn bad when a contact lens is introduced onto the ocular surface. Treatments that target the changes in tears, such as anti-allergy drops or cyclosporine, may be helpful in returning the tear film to its normal state.

When a contact lens patient presents complaining of itching, dryness, redness, discomfort or reduced wearing time, go back and take a look at the history and exam findings from the pre-fit evaluation. Most likely, there was no indication of allergy or dry eye; if there was, you probably addressed it prior to starting contact lens wear. How-ever, by revisiting the same questions, the patient may provide more information.

Patients dont always understand that the eyes response to allergy is different from systemic response. The patient can present with eye symptoms and not think of it as allergy, says optometrist William Potter of Freehold, N.J. Some-times youll find out the patient has taken allergy medications, and never told you about it.

Your listening skills will be critical at this point. Ask the patient to pinpoint when symptoms first appeared, and how those symptoms have manifested since then.

Your initial exam for new contact lens patients may foretell problems from allergy or dry eye. Dr. Rinehart performs two important tests on potential contact lens wearers. First, he everts the upper lids to check for giant papillary conjunctivitis. If he observes GPC at the initial exam, he can forewarn the patient about allergies. Second, he expresses the meibomian glands to evaluate tear quality.

Its important to do both of these so you have a baseline, Dr. Rinehart says. Down the line, if there are problems, you have something to compare it to. If the lids were clear to start, the problem is likely to be an allergic reaction to buildup on lenses.

Red Flags

Research has shown that contact lens intolerance appears to be best predicted by a combination of such variables as tear film stability, tear volume and patient symptoms. As you review the patient history and compare current and previous clinical findings, youll start to differentiate between allergy and dry eye, particularly when you consider:

Patient symptoms. Does the patient report itching or burning? The hallmark of allergy is itching, whether the patient is a contact lens wearer or not, says optometrist John Schachet of Englewood, Colo. Dry eye patients will have burning and/or foreign-body sensation. This isnt the only way to differentiate, but it gives you a direction to investigate further.

Clinical findings. Optometrist Christine Sindt, assistant professor at University of Iowa, says she looks for deposits on the contact lenses, which may indicate dry eye or contact lens related problems. She also looks for conjunctival reactions (both palpebral and bulbar), which may indicate allergy; tear quality and breakup time to diagnose whether dry eye exists; and staining on the cornea or conjunctiva, another hallmark of dry eye.

A note about staining: Meibomian gland dysfunction can cause or exacerbate corneal staining by increasing tear evaporation, or by direct toxicity from staphylococcal exotoxins or free fatty acids, says optometrist Arthur B. Epstein of Great Neck, N.Y. This type of staining occurs primarily in the inferior cornea.

External factors. Asuza, Calif., optometrist Milton Hom, author of Ocular Drug Consult, says external factors can help in your differential diagnosis. Allergies often occur when pollen counts are high. Dryness usually occurs with certain environmental conditions and when patients perform certain tasks such as reading, watching television or using a computer for more than 30 minutes at a time (task-based dryness), he says.

The Diagnosis

Still, the challenge is to unravel the signs and symptoms. A patient may have dry eye secondary to allergies, or dry eye with lens-related allergy that exacerbates the situation.

A dry eye can aggravate allergies. As tear volume decreases and viscosity increases, antigenic particles become trapped on the ocular surface, exacerbating allergic conditions, Dr. Sindt says. Patients often experience itch from dry contact lenses, although the itching may not be caused by allergies.

Even after youve arrived at a tentative diagnosis, your work is not done. If you determine that allergy is responsible for the patients symptoms, you must sort out whether it is seasonal or related to the lens or solution. For example, GPC may be the result of denatured protein on the contact lens.

Oftentimes, Dr. Schachet says, changing the contact lens solution can solve the patients problem. It doesnt make any difference how long the patient has been wearing contact lenses, he says. We take for granted they are complying with the wearing schedule and cleaning regimen, [and that] theyll stay on the solution we recommend, he says.

Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Even a long-term contact lens wearer may switch solutions and develop hypersensitivity. A new wearer is easier, because you will spot it sooner, and change the solution, he says.

If the signs suggest dry eye rather than allergy, Schirmer test and/or lisamine green will help you assess tear flow. Look for superficial punctate keratitis (SPK), conjunctival inflammation, decreased tear breakup time and decreased tear meniscus.

Related Treatment Strategies

Just as the diagnoses for dry eye and allergy are interrelated, so are the treatment approaches.

In my practice, the majority of the treatments for the two conditions are similar. There is a very strong association between dryness and allergy. Approximately one-third of the allergy patients have a primary tear film deficiency, says Dr. Hom.

The armamentarium of allergy and dry eye drops is essential. However, in addition, some dry eye patients can benefit from what Dr. Rinehart describes as old-fashioned treatments. For example, he estimates that 75% or more dry eye patients have meibomian gland dysfunction. If we get the glands open and functioning, a lot of problems subside, he says. At the initial exam, he tries to express glands. If its difficult, he starts them on hot compresses and lid massage nightly (or morning and night) before he puts the patient in contact lenses.

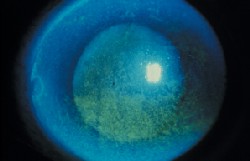

Meibomitis in a contact lens wearer.

Dr. Sindt also takes a proactive approach with new contact lens wearers. I discuss lid hygiene right up front, she says. Lid hygiene reduces antigen load and opens the meibomian glands. If a patient already has a history of allergies, I discuss treatment options before we start with contact lenses, to proactively open communication. I recommend specific solutions and wetting drops and explain why they are the best choice for them.

The key to reducing dropout initiated by allergy or dry eye is to retrace your steps and move forward with diagnostic tests, until the root cause is evident. At that point, theres an effective armamentarium of pharmaceuticals, artificial tears and management strategies that will keep most patients in contact lens wear.