|

|

|

A 43-year-old white female presented for a routine examination. Her only complaint was near vision difficulty related to presbyopia. She had a history of breast cancer with mastectomy, for which she was taking tamoxifen. Her other medications included Lupron (leuprolide acetate, AbbVie) and vitamin D. Her past ocular, family and social history was unremarkable.

Her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 OD and OS. Ocular motility was full with no limitation, with no afferent pupillary defect, and she was orthophoric in primary and lateral gazes in both eyes. She noted 10/10 color plates in each eye.

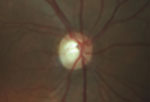

Intraocular pressure measured 15mm Hg OD and 16mm Hg OS. The anterior segment exam was unremarkable. Fundus exam showed cup-to-disc asymmetry OD>OS, and evidence of disc pallor in the right eye.

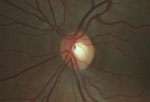

Although she was asymptomatic, we ordered spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) and visual field testing due to the presence of both cup asymmetry and optic nerve pallor. The SD-OCT showed significant nerve fiber layer thinning of the right disc, with moderate asymmetry compared to the left. Her left optic nerve was normal. Visual field showed subtle temporal field defects in the right eye that respected the vertical meridian. The left field was normal.

|

|

|

Fundus exam shows asymmetric cupping, with the right eye (left) greater than the left eye (right), and evidence of disc pallor in the right eye.

|

|

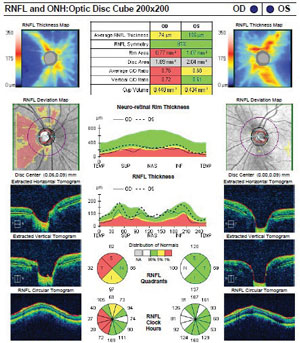

The findings of cupping and pallor, generalized depression of the nerve fiber layer and centralized temporal field defects respecting the vertical midline pointed to a non-glaucomatous etiology. Given her history and demographics, the differential diagnosis included demyelinating disease, a primary or metastatic intracranial space occupying lesion and immune-related optic neuropathy. Consequently, she was scheduled her for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with and without contrast and fat suppression.

Imaging studies revealed a lobulated aneurysm on the right side in the region at or above the cavernous sinus, which compressed the right optic nerve.

The patient was referred to neurosurgery, where she had cerebral angiography that localized a bi-lobed right internal carotid artery para-ophthalmic aneurysm. The two lobes measured 8mm and 6mm. She underwent successful pipeline embolization of the aneurysm. As of her last follow-up, she was doing wonderfully. There was no further damage to her optic nerve.

| |

|

|

SD-OCT shows significant nerve fiber layer thinning of the right disc, as well as moderate asymmetry compared to the left disc. |

Discussion

Optic atrophy is caused by damage to ganglion cells and axons of the optic nerve.1

This can be a result of ischemia, inflammation, compression, infection or trauma.1

Ischemic optic neuropathy, optic neuritis and papilledema are the more common conditions that can lead to optic atrophy, although the complete list of differentials is extensive.

Determining the etiology of optic atrophy can be challenging, as there are multiple causes. A careful history and examination often pinpoints the cause, but unexplained optic atrophy needs to be explored. In one study, compressive lesions were the etiology in 20% of patients with isolated and unexplained optic atrophy.2 As a result, neuroimaging is warranted in all patients with unexplained optic atrophy. The preferred modality is MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast and with fat suppression.2 If there is a contraindication to MRI, computed tomography (CT) may be used instead.2

Lab testing is of low yield unless historical or exam elements suggest an underlying etiology.2 Common lab tests for evaluation of optic atrophy include Lyme titer, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), rapid plasma reagin (RPR), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), Bartonella titer, antinuclear antibody (ANA), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). The recommendation when considering lab studies is to tailor based on suggestive history, exam findings or endemic locations that may suggest a greater likelihood of diagnosing conditions such as syphilis, Lyme disease or sarcoidosis.2 If the patient has a prior diagnosis of optic atrophy, be sure to obtain past medical records, imaging reports or laboratory studies, and document those in the patient’s chart.

This case also highlights the importance of distinguishing glaucomatous optic neuropathy (GON) from non-glaucomatous optic neuropathy (NGON), the latter of which was seen in our patient. Optic nerve cupping is most frequently caused by glaucoma, yet compressive lesions can cause secondary optic disc excavation and mimic glaucoma.1 While cupping asymmetry has a high predictive value of GON, the key clinical finding that helped distinguish GON from NGON in this patient was pallor of the neuroretinal rim, which is 94% specific for a non-glaucomatous etiology.3,4

|

|

|

MRI shows a lobulated aneurysm on the right side in the region at or above the cavernous sinus, which compressed the right optic nerve.

|

|

Ancillary studies that helped to confirm NGON were the use of formal visual field testing and SD-OCT. Visual fields are an invaluable asset in distinguishing glaucoma from neuro-ophthalmic-related optic nerve disorders. In the setting of presumed optic atrophy, a vertically-oriented centralized temporal field defect indicates an etiology other than glaucoma and prompts further investigation. Additionally, SD-OCT has been shown to distinguish glaucomatous from compressive optic neuropathies by analyzing patterns of nerve fiber layer loss. Specifically, cupping from NGON is associated with thinner nasal and temporal sectors when compared to that of glaucomatous disease.5 In our patient, the SD-OCT revealed significant nerve fiber layer loss in all quadrants when compared to the fellow eye. Lastly, her younger age, normotensive and symmetric IOPs and healthy disc in the fellow eye were all red flags for NGON.

Assuming there have been no acute vision changes or neurologic deficits, working up optic atrophy is generally non-urgent because the atrophic process takes a minimum of six weeks to develop. So, visual field, OCT and MRI/laboratory studies can be obtained within a few weeks.

This case highlights the importance of evaluating unexplained optic atrophy and differentiating GON from NGON. In-office assessment of the disc with digital photography, visual field testing and SD-OCT are invaluable in differentiating glaucoma from alternative neuro-ophthalmic pathology.

In this patient’s case, while there were subtle findings of pallor, there was no afferent pupillary defect, the visual acuity and color vision were normal and the patient was asymptomatic. So, in the presence of optic nerve asymmetry, consider alternative diagnoses and perform a detailed inspection of the neuroretinal rim for color changes that are not consistent with a glaucomatous process.

1. Fraser CL, White AJ, Plant GT, Martin KR. Optic nerve cupping and the neuro-ophthalmologist. J Neuroophthalmol. 2013 Dec;33(4):377-89.2. Lee AG, Chau FY, Golnik KC, et al. The diagnostic yield of the evaluation for isolated unexplained optic atrophy. Ophthalmology. 2005 May;112(5):757-9.

3. Sharma BD, Chaturvedi RP. Disc-cup asymmetry in normal and chronic simple glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1982 May;30(3):133-4.

4. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Kerrison JB. Walsh & Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology: The Essentials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2007.

5. Danesh-Meyer HV, Yap J, Frampton C, Savino PJ. Differentiation of compressive from glaucomatous optic neuropathy with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2014 Aug;121(8):1516-23.