We are all familiar with glaucoma and the intricacies of its diagnosis. Under ideal conditions, we would like to obtain multiple intraocular pressure (IOP) readings, gonioscopy, pachymetry, optical coherence tomography (OCT) evaluation, reliable threshold perimetry, optic disc evaluation with high quality fundus photography and a detailed medical and ocular history with assessment of all risk factors. But once we have all this information—or as much of it as we can uncover—what is the next logical step? How can optometrists keep their glaucoma patients in their offices and in good health?

No one “cookbook” approach to managing glaucoma patients is possible. Every patient must be treated as an individual, and that requires some deft maneuvering from skilled clinicians. This guide is designed to give optometrists the grounding they need to know which decisions to make, and the testing protocols that can provide the basis for those decisions.

On the Range

When commencing glaucoma treatment, start by setting a target pressure; that is, an IOP range that best estimates the disease’s impact and impact of treatment. Target IOP should be individualized, with consideration not only of the patient’s maximum peak untreated IOP, but also the amount of damage that has occurred. Other relevant factors include the patient’s age, life expectancy, family history, status of the fellow eye and risk of visual disability. Secondary factors such as exfoliation may necessitate a lower target IOP than primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) due to relative severity.

With an increase in life expectancy and a general trend towards an aging population, the prevalence of ocular diseases, which tend to be more common in increased age, will also grow. More than ever, we find ourselves managing patients for an extended period—including many who are in their 80s and 90s. The treatment decisions that we make early on with a patient can impact them 30 to 40 years down the road. Though longevity is an important factor in assessing risk of visual disability, take care not to make false assumptions about how long an elderly patient is likely to live.

We typically choose an IOP range, rather than a single target number, to allow for variability. If we note progression at any point during therapy, we adjust the target downward. Typically, a 30% reduction from the peak IOP is reasonable in mild cases; however, a more aggressive reduction is often required in advanced disease to slow vision-threatening progression. In advanced disease, we feel that a 50% or greater reduction may be more appropriate. Target pressure, once set, should be adjusted throughout a patient’s management. Patients who seem to have similar risk profiles for progression often progress differently, and target pressure should be adjusted to reflect this. Keep in mind that target IOP is merely a “best guess” and the patient must be monitored closely to assess disease stability.

When embarking on therapeutic pressure reduction, most practitioners opt to start medically with prostaglandin analogs (PGAs), which have a strong efficacy and safety profile.1 This practice is so common today that there should be a reason recorded in the chart if a patient is not on a PGA (e.g., adverse effects, cost, medical contraindication).

If the patient does not achieve the target pressure with the PGA, you can consider adjunctive therapies. Topical options include beta blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, alpha-adrenergic agonists or polytherapy fixed-combination drugs. There is synergy between PGAs and these other classes, and choice is typically dictated by the patient’s medical history and possible contraindications.1

While medication is the most common first-line therapy for newly diagnosed glaucoma patients, we do discuss selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) as a first-line option with our patients. Working with a patient to determine what they consider to be most important helps to determine your management plan. Those patients with mild-to-moderate disease who also have a history of intolerance with topical medications, severe corneal surface disease, difficulty with drug instillation or a preference to avoid topical therapy are suited for SLT as a first-line therapy.

General health status, patient autonomy and access to transportation may also impact your first line treatment choice. Other patient factors play a role in determining candidacy for SLT, including amount of pigment in the trabecular meshwork and angle configuration.2 ODs should always discuss with these patients the risks and benefits of treatment and risks of any alternative approaches.

Regardless of your chosen first-line treatment for newly diagnosed patients, having the patient involved in your plan will improve adherence to the management strategy.

|

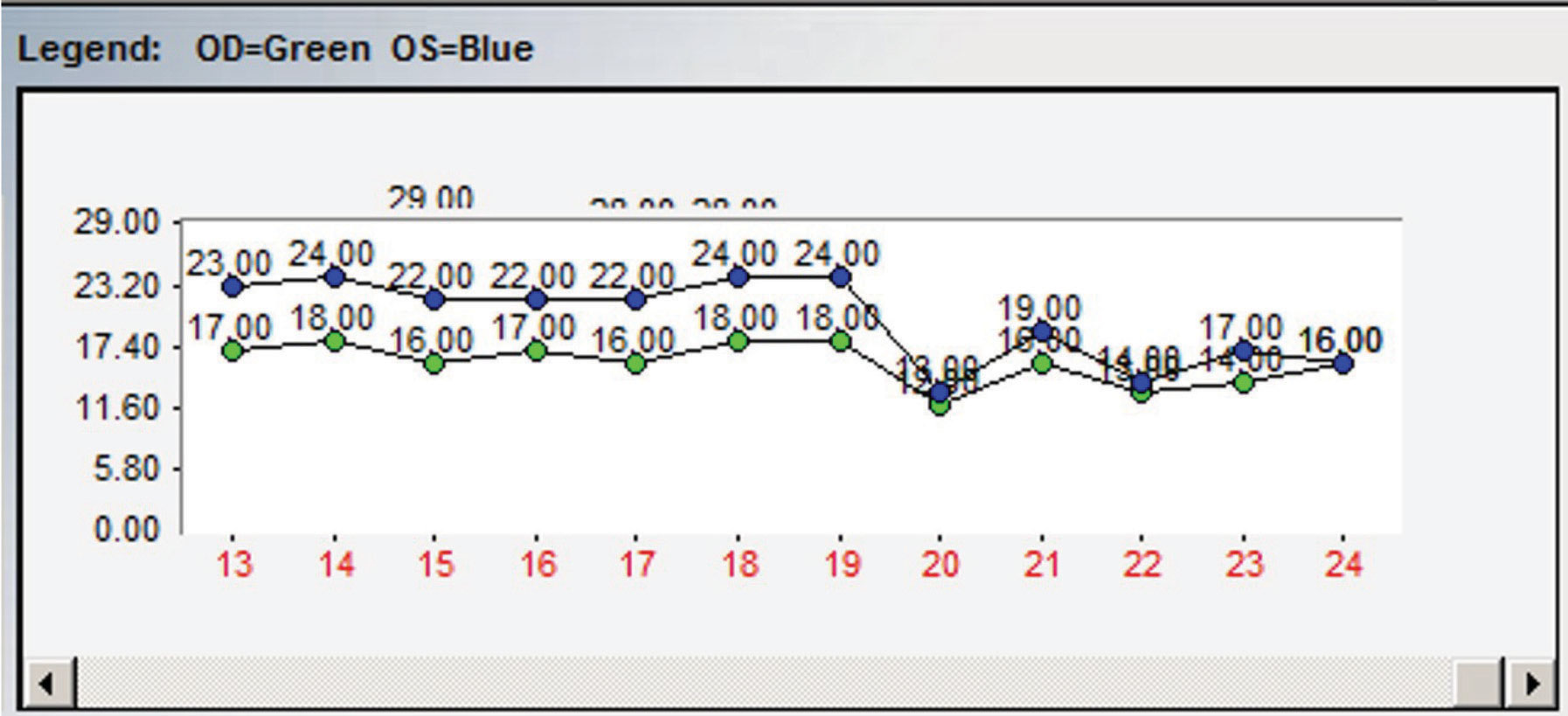

| Fig. 1. This chart demonstrates an example of the importance of multiple IOP readings. At point 19, topical therapy was initiated with an apparent reduction in IOP noted at point 20. However, when assessing the entire IOP profile, it is apparent that there are post-treatment readings nearly identical to pre-treatment readings. |

Nix Monocular Drug Trials

The concept of monocular drug trials is to use the non-treated eye as a control to compare the IOP reduction in the treated eye and determine medication efficacy. In theory, this sounds like an excellent idea, but in clinical practice it isn’t so simple, or as accurate, as you may think.

While IOP fluctuates, it does not fluctuate symmetrically between the two eyes, so the untreated eye is a poor control for the treated eye.3 Also, the variability in IOP fluctuation at certain points during the day, (e.g., at 9am), is also not symmetric between the eyes. Some topical IOP-lowering medications, such as beta-blockers, can exhibit a crossover effect, lowering pressure in both eyes, even if only applied to one. This is a less of a concern with PGAs.4 With the expansion of our knowledge of IOP fluctuations and variability, as well as drug metabolism, monocular drug trials no longer provide significant information. Once we decide that a patient needs treatment bilaterally, we initiate therapy in each eye simultaneously.

Establishing a Baseline

For glaucoma patients new to our clinic who have not yet begun IOP-lowering therapy and for whom previous records are not available, we take multiple pre-treatment IOP measurements over the course of several visits to establish true baseline, untreated peak IOP and to have a better understanding of their IOP variability, whenever possible. This is not something we would do in patients with advanced disease who’ve already experienced central visual field loss, but for the majority of patients, two weeks without medication is unlikely to cause clinical progression. We also try to take IOP measurements at different times of day. That is, if we typically see a patient first thing in the morning, scheduling an appointment later in the day can help to improve your understanding of a patient’s IOP variability and fluctuation.

Once we initiate treatment, we do not judge efficacy based upon a single reading either. In many instances a pre-treatment IOP is similar to a post-treatment IOP. Without this knowledge, errors are likely (Figure 1).

For patients newly using a PGA, have them return for a follow-up visit approximately one month after medication initiation. It can be easy to jump to a conclusion of poor response to the medication if you measure only modest reduction from baseline IOP at this first visit. Remember, IOP fluctuates. On this particular visit, maybe you caught them on an up-swing and, overall, the medication is working as you would expect it to. Don’t be fooled. Therapeutic decisions should be made upon several IOP measurements. Having the patient return in another few weeks to again assess IOP—at a different time of day—will give you another important piece of information on how well a particular medication may be working, before making a treatment decision.

Staying in Control

Most practitioners will determine a patient is “well-controlled” after therapeutic IOP reduction achieves the set target. However, initially the only thing that can be truly said is that the IOP has been reduced. The term, “well-controlled” should only be used in retrospect, after the patient has been followed for a period without change. We believe in close follow-up. That is, once our initial evaluation is complete and the patient is at target, we like to assess progress every three to four months so IOP can be measured and adherence to therapy can be assessed. In low-risk ocular hypertensive patients and those with glaucoma who have remained stable over years, evaluations can be done every six months.

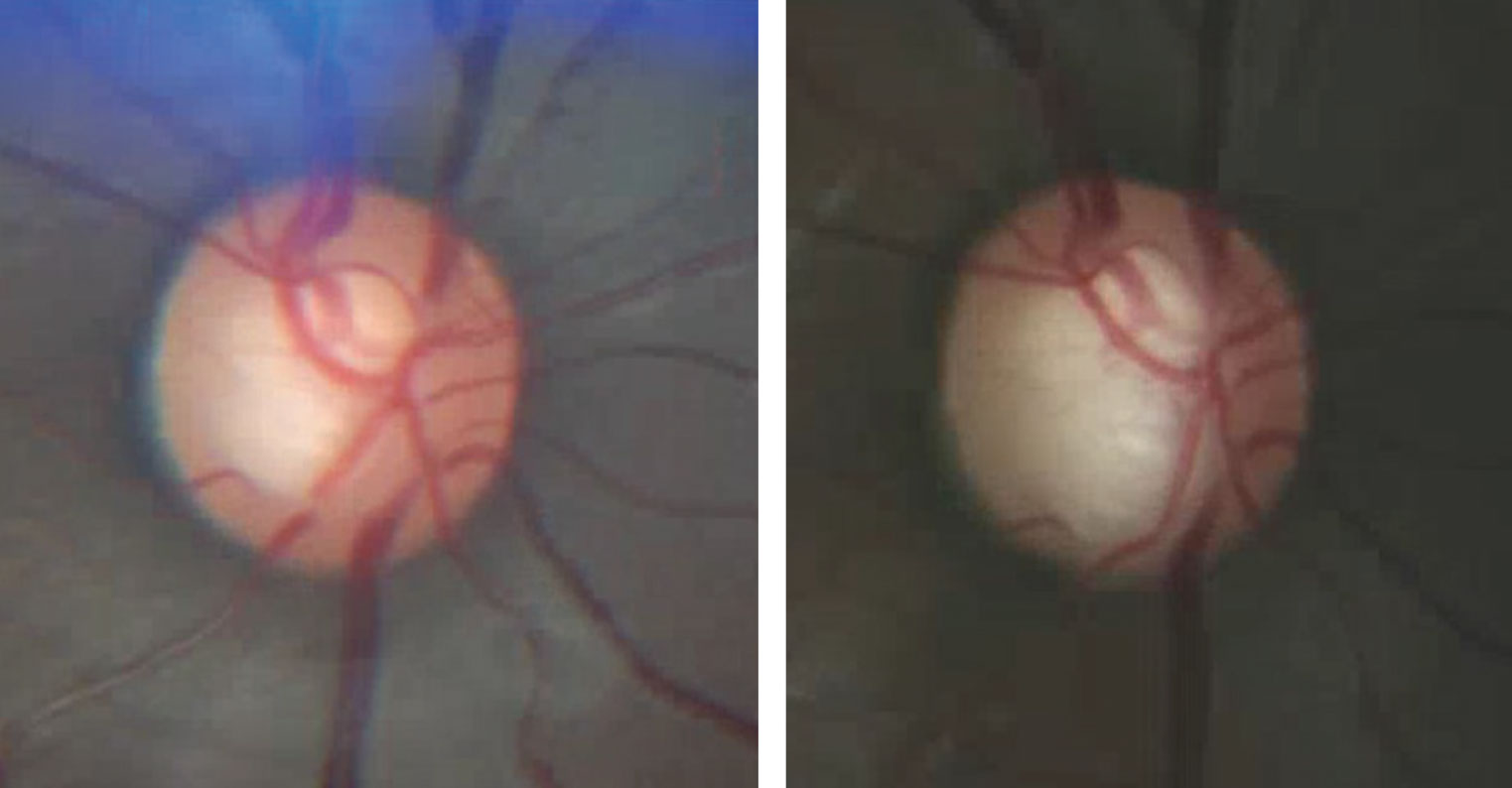

Evaluation of the optic nerve head should be performed at every follow-up visit. We perform an undilated optic disc evaluation with a 90D or superfield lens at each visit and perform a complete dilated fundus examination with optic disc photography once per year. The goal of optic disc examination at each visit is to observe an optic disc hemorrhage—which are easy to miss clinically, unless you’re specifically looking for them. Optic disc photography is the only true way to accurately assess the optic disc for change (Figure 2).

|

| Fig. 2. This photographic comparison of a glaucoma patient’s right optic disc show the baseline (at left) and one taken several years later. Note the changes in both the superior and inferior neuroretinal rim. Baseline and annual optic disc photography is an essential part of managing glaucoma patients. |

Imaging

Like optic disc photography, OCT is a valuable structural measurement that should be repeated every six to 12 months. However, the role of fundus photography and OCT is limited in advanced disease. The retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) is comprised of more than just axons of retinal ganglion cells—it also contains glial support cells and blood vessels, which all contribute to the RNFL’s measurable thickness. Even with complete loss of axonal damage in a focal region, the measurement will never go to zero and tends to bottom out, depending on the device being used, at approximately 50µm to 55µm. After the RNFL thickness reaches approximately 55µm, even with further disease progression (which can be detected through functional measures) the structural OCT parameters will appear stable.5

While gonioscopy is needed for determining the nature and mechanism of a patient’s glaucoma diagnosis, it’s not a one-and-done test. Gonioscopy should be periodically repeated throughout the course of management of a patient. In open-angle glaucoma patients, we typically repeat gonioscopy every two or three years, or sooner if clinical findings suggest a change. For example, if a treated patient with minimal IOP variability presents with unexpectedly elevated IOP, assess for proper therapy adherence and check the angles gonioscopically.

Secondary causes of elevated IOP include angle recession, exfoliation syndrome, pigment dispersion, peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) or neovascularization of the angle. These can all be determined through a gonioscopic evaluation. Additionally, through the process of cataractogenesis, a patient with a previously open angle can develop a phacomorphic chronic angle closure necessitating alternate treatments.6

OCT can visualize the anterior chamber angle, but when assessing the anterior chamber, its significant limitations make it a useful adjunct but not a replacement for gonioscopy. In a primary angle closure suspect, OCT performed in complete darkness, without unintended indentation, may give you additional objective information about the angle structure, and may be more likely to exhibit appositional closure than gonioscopy. However, OCT does not provide information about trabecular meshwork pigmentation, the presence of PAS (although iris-trabecular meshwork contact can be observed), and dynamic observation through indentation gonioscopy cannot be performed with OCT.7

Predicting Progression

Pachymetry should be done only once and not repeated unless there is an unusual change in the cornea such as keratorefractive surgery, trauma or degenerative disease. Pachymetry should be performed on every glaucoma patient and suspect. As a general concept, the thinner the cornea, the greater the risk for disease development.8 However, repeated measurements are not necessary.

We like to perform threshold perimetry every six months and will reduce the frequency of testing to every 12 months if a patient shows stability over several years. While doctors and patients seem to dislike perimetry, it is a mandatory part of glaucoma management. Performing perimetry at the initial encounter and then only annually is too infrequent to properly assess for early functional progression.

The rate of progression between patients, even with seemingly similar risk profiles, varies greatly. To identify those patients who may be undergo rapid disease progression early, six visual fields performed within the first two years of diagnosis are recommended.9 This recommendation is based on the statistical power needed to accurately identify a change in mean deviation to identify those patients most at risk for more rapid disease progression. This information enables practitioners to identify patients who may be rapid progressors and institute aggressive treatment. Once this data has been accumulated, visual fields can be performed every six months and, in cases where the patient is stable for a period of time, then annually. Due to the testing variability in perimetry, ODs should have the patient back in a month or two to repeat the test and see if the change persists and is representative of a worsening field or just one bad testing day.

Adherence

One of the most challenging aspects to medically managing glaucoma is patient adherence to therapy.10 Adherence to treatment through observance and persistence is mandatory, and identifying the causes of nonadherence is crucial. These factors could include the patients themselves (e.g., doubt, forgetfulness, denial), environmental factors (e.g., cost, competing activities, travel), the treatment regimen (e.g., refill, side effects, complexity) and, finally, the relationship with the clinician. Optometrists should presume that patients have low adherence to their treatment and give clear and precise information about the expected benefits of the treatment, the disease and its risks of progression.11

A study conducted in 2005 found that nearly half of the individuals who had filled a glaucoma prescription discontinued all topical ocular hypotensive therapy within six months, and just 37% of these individuals refilled their initial medication at three years after the first dispensing.12 Prostaglandins are associated with better persistence and adherence than any other drug class. Furthermore, patients with diagnosed glaucoma were more likely to adhere to therapy than patients with merely suspect glaucoma. Education about glaucoma and the potential visual disability has been shown to enhance therapeutic adherence.12

We have found that the best way to enhance medical therapy adherence is through repeated education to the patient and any family members about glaucoma and the visual consequences of not adhering to treatment. Providing written material explaining the disease in patient-friendly language is invaluable. While doctors can create their own specific written messages, we typically employ glaucoma information sheets made available by pharmaceutical companies. These brochures are very well done, readily available and are not product-promotional in any way (except for perhaps a small company logo). We obtain these directly from drug companies and their representatives and find them invaluable in our patient education.

|

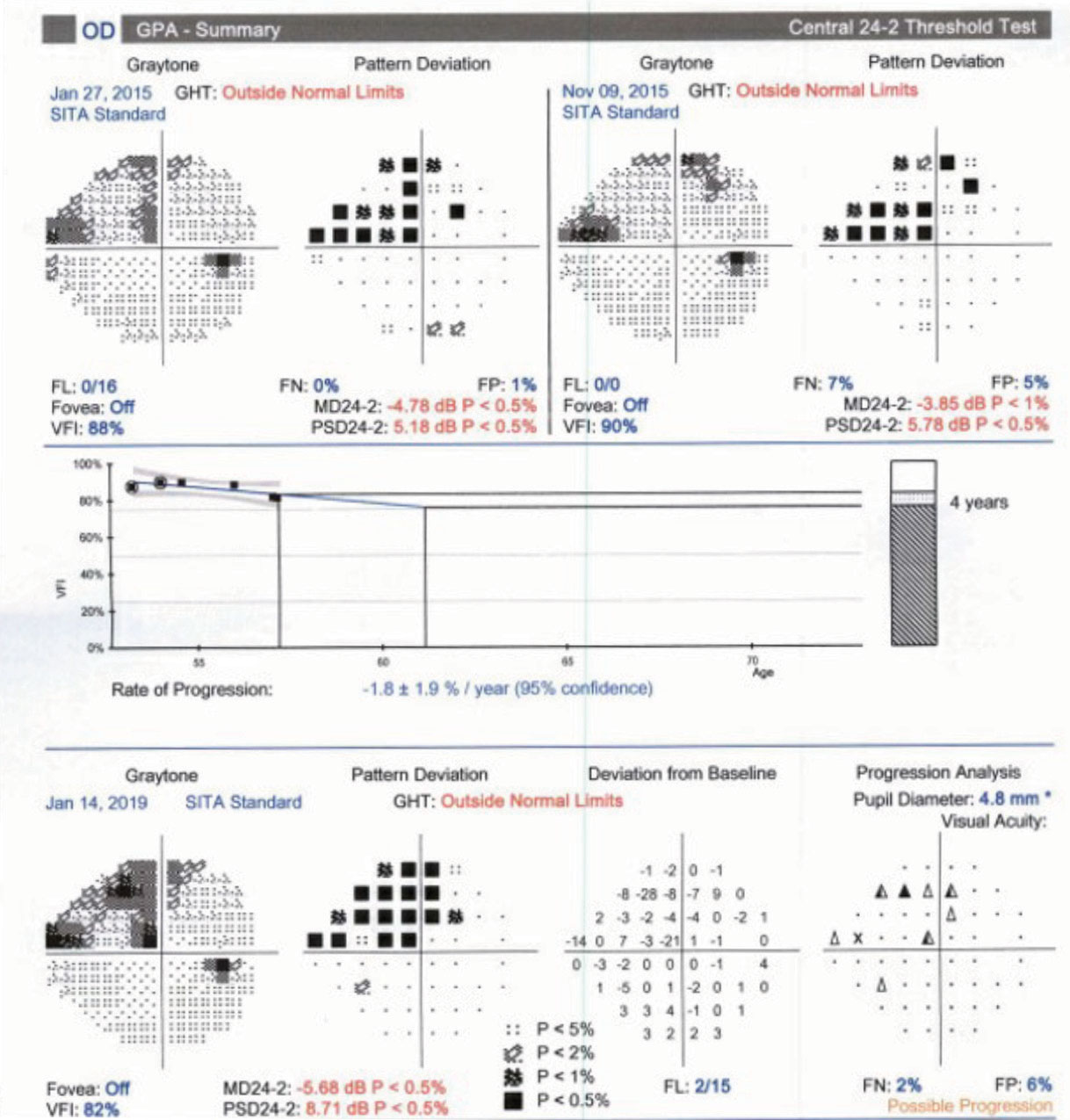

| Fig. 3. Proper periodic repetition of threshold perimetry allows clinicians to employ a guided progression analysis to determine if glaucoma has progressed and at what rate the progression has occurred. |

Better? Or Worse?

Differentiating clinically relevant progression from inherent variability and fluctuation is one of the biggest challenges in managing glaucoma patients. While some identifiers of progression, such as upward trending IOP, above your target pressure, optic disc hemorrhage, new wedge or nerve fiber layer defects are relatively objective. Assessing progression using adjunctive tests such as OCT and visual fields can be more challenging. Other factors tend to muddy the waters of progression identification further—the amount of baseline damage, the patient’s age and IOP may all have different relative weights in your threshold for determining clinically relevant progression.

While optometry has not identified a single standard for identifying progression, a combination of functional, structural and clinical data contribute to the identification of clinically meaningful change. While most patients with glaucoma progress slowly, those who may progress quickly are at significant risk of vision loss, even with treatment, and it’s necessary to identify them early. This can be achieved with OCT, perimetry systems, progression analysis software, visual field and OCT RNFL evaluation.13

Progression analysis software removes the ambiguity of a normative database and compares RNFL thickness of a patient to their own baseline to determine change over time. This means that the raw baseline images for every patient should be checked to ensure that they are of good quality, well-centered, without missing data points, and that the automated segmentation has been performed correctly; otherwise, with an inaccurate baseline, true progression may be masked or true stability may appear as progression. Also, if you’re performing multiple scans of the same type on the same day, delete the poorer quality images; otherwise, the device will automatically include the scan, which was performed first in the progression analysis.

When analyzing the guided progression analysis information, keep in mind that some age-related decrease in RNFL is expected.14 Typically, a change of 10µm of average RNFL thickness (or at least twice the inherent variability in measurement) is recommended before considering real change as a possibility.15 Proprietary differences in imaging software between manufacturers exists, so if you are imaging a patient on different instruments of different manufacturers, while the general trends of data is valuable, direct RNFL and GCC thickness parameters cannot be directly compared between instruments.

While structural tests such as OCT do not require patient input, they are still subject to measurement errors and inconsistencies that can lead to perception of progression in the absence of real change. Functional evaluation, using visual field analysis, is a mainstay of glaucoma management and key data to incorporate when determining if a patient may be progressing. Amassing a number of reliable visual fields is essential to employ a guided progression analysis to determine if change is not only taking place but also the rate at which the progression is occurring (Figure 3).

|

| This worksheet was designed to help you learn more about glaucoma and how to diagnose and manage it. Feel free to photocopy it and use it in your own practice. Click image to download. |

Individualize Care

In general, most patients seek care when they have a specific problem—with their goal being improvement of that problem with treatment. However, managing glaucoma requires a shift in our patient’s understanding of the typical ‘problem-prescription-cure’ algorithm. The clinician’s goal in managing patients with glaucoma, which is central for patients to understand, is not to cure the condition or improve functionality or quality of life—but instead to prevent functional decline or to prevent reduced quality of life. This isn’t the same thing as simply lowering the IOP, or preserving the nerve fiber layer—over-prescribing can be just as harmful as under-prescribing. Adverse effects and the significant impact of the cost of medications all impact a patient’s quality of life.

Quality of life as it relates to glaucoma describes the feeling or perception that the patient has about how they are functioning. For example, if a patient has a paracentral defect, which has slowed their reading speed, how does she feel about this change? For some patients this may be a minor inconvenience, but for others, this may have a drastic impact on their quality of life. Along the same line, take patient concerns seriously. If that same patient reports that she has been having worsening difficulty reading, consider that this change could be related to disease progression. In this case, a 10-2 visual field may highlight a deepened paracentral defect, which may result in a change in therapy.

Simply asking a patient how they’re feeling and managing with their medications, especially when patients may be facing functional vision loss, can go a long way. Although we’re not professional counselors, identifying when a patient may be having difficulty dealing with vision loss and recommending that they discuss these challenges with their primary care doctor or with a counselor while arranging for low vision services can have a significant impact on a patient’s well-being.

Despite our growing understanding of the complex pathophysiology of glaucoma, we still only have one option to slow disease progression—reducing the pressure. Luckily, we have a number of pharmaceutical options to accomplish that, but their use must be paired with proficient clinical acumen. This means navigating the patient’s risk factors for progression, setting a target pressure range and being ready to change that initial target by monitoring changes using available technology.

Dr. Steen is an attending optometrist and assistant professor of ocular pharmacology at Nova Southeastern University College of Optometry.

Dr. Sowka is chief of advanced care and director of the glaucoma service at Nova Southeastern University College of Optometry.

1. Tanna A, Lin A. Medical therapy for glaucoma: what to add after a prostaglandin analogs? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(2):116-20. 2. Katz LJ, Steinmann WC, Kabir A, et al. SLT/Med Study Group. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus medical therapy as initial treatment of glaucoma: a prospective, randomized trial. J Glaucoma. 2012;21(7):460-8. 3. Sit AJ, Liu JH, Weinreb RN. Asymmetry of right versus left intraocular pressures over 24 hours in glaucoma patients. Ophthalmol. 2006;113(3)425-30. 4. Realini T, Weinreb RN, Wisniewski S. Short-term repeatability of diurnal intraocular pressure patterns in glaucomatous individuals. Ophthalmol. 2011;118:1:47-51. 5. Leung CKS, Ye C, Weinreb RN, et al. Impact of age-related change of retinal nerve fiber layer and macular thickness on evaluation of glaucoma progression. Ophthalmol. 2013;120(12):2485-2492. 6. Nguyen CT, He Z, Luo K. Conversion of primary to phacomorphic angle-closure glaucoma: case report. Clin Exp Optom. 2016;99(6):604-6. 7. Smith SD, Singh K, Lin SC, et al. Evaluation of the anterior chamber angle in glaucoma. Ophthalmol. 2013;120:1985-97. 8. Gordon M, Beiser H ,Brandt J, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):714-20. 9. Chauhan BC, Garway-Heath DF, Goni FJ, et al. Practical recommendations for measuring rates of visual field change in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(4)569-73. 10. Reardon G, Kotak S, Schwartz GF. Objective assessment of compliance and persistence among patients treated for glaucoma and ocular hypertension: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:441-63. 11. Nordmann JP, Akesbi J. Improve adherence in glaucoma patients: a doctor’s duty. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2011;34(6):403-8. 12. Nordstrom BL, Friedman DS, Mozaffari E, et al. Persistence and adherence with topical glaucoma therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(4):598-606. 13. Leung CKS, Liu S, Weinreb R, et al. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer progression in glaucoma: a prospective analysis with neuroretinal rim and visual field progression. Ophthalmol. 2011;118:1551-7. 14. Leung C, Ye C, Weinreb R, et al. Impact of age-related change of retinal nerve fiber layer and macular thickness on evaluation of glaucoma progression. Ophthalmol. 2013;120(12):2485-92. 15. Mwanza J, Chang R, Budenz D, et al. Reproducibility of peipapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and optic nerve head parameters measured with Cirrus HD-OCT in glaucomatous eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(11):5724-30. |