|

A 30-year-old black male presented with blurred vision in his right eye. He said he had been experiencing this problem for the past two weeks. He also said he had experienced a rather sudden loss of vision over a few days.

He reported no vision problems in the past, and denied any injuries or infections. His medical history was unremarkable, and he said he didnt take any medications.

Visual acuity measured 20/30 O.D. and 20/20 O.D. Extraocular motility was normal. Confrontation fields were full to careful finger counting O.U. The pupils were briskly reactive without afferent pupillary defect. Anterior segment exam was unremarkable. IOP measured 13mm Hg in both eyes.

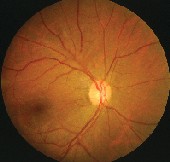

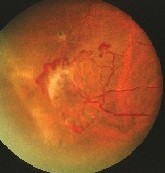

Dilated fundus exam revealed 1 to 2+ cells in the vitreous O.D., but the vitreous was clear O.S. Both optic nerves appeared healthy, with a small cup and good rim coloration and perfusion. The right fundus appearance is shown in figure 1. There were retinal changes temporally and superiorly O.D. (figures 2 and 3), and fibrous changes infero-temporally in the peripheral retina O.S. (figure 4).

|

| 1. Posterior pole view O.D. shows an area of haziness along the superior arcade. |

1. How would you explain this patients blurred vision?

a. Macular edema.

b. Macular ischemia.

c. Vitreous hemorrhage.

d. Retinal detachment.

2. What do the changes in the peripheral retina O.D. represent?

a. Neovascularization of the retina.

b. Sea fans.

c. Retinal angioma.

d. Eccentric neovascular membrane.

3. What additional testing is likely to be abnormal?

a. Blood pressure.

b. Fasting blood glucose.

c. Hemoglobin electrophoresis.

d. Hemoglobin A1C.

4. What is the correct diagnosis?

a. Resolved ischemia from a central retinal vein occlusion.

b. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

c. Eales disease.

d. Proliferative sickle cell retinopathy.

5. What is the appropriate management for this patient?

a. Observation.

b. Focal laser photocoagulation.

c. Scatter panretinal laser photocoagulation.

d. Pars plana vitrectomy.

|

|

| 2, 3. Suspicious peripheral retinal lesions appeared temporally (left) and superiorly in the right eye. |

Discussion

The peripheral retinal changes in this patient represent active neovascular fronds. There is also an area of fibrous proliferation from older neovascularization that has autoinfarcted. Note that the changes we see are isolated to the peripheral retina and not to the posterior pole, which is essentially normal.

Given the patients negative systemic history, we initiated a work-up, as we were highly suspicious of sickle cell anemia. Hemoglobin electrophoresis was positive for sickle cell-hemoglobin E (HbE) disease, a very rare form of sickle cell anemia.

Sickle-cell disease, an inherited multisystem disease that occurs predominantly in black people, is caused by abnormal red blood cells.1 These cells contain mutant sickle cell hemoglobin (HbS), which results in sickling of the erythrocytes. The abnormal erythrocytes cause obstruction of the microcirculation because of their abnormal shape. This results in lack of oxygen to the tissues, leading to chronic hemolytic anemia, episodes of recurrent pain and organ dysfunction.

There are several types of sickle cell syndromes based on inheritance patterns and mutations within the sickle cell gene. These syndromes are divided into sickle cell anemia and sickle cell trait. Those who have anemia may develop the systemic complication, while the traits are largely asymptomatic. The common types of sickle cell hemoglobinopathies (Hb) include SS (sickle cell anemia), CC (hemoglobin C disease), SC (sickle cell-hemoglobin C disease), AS (sickle cell trait), AC (hemoglobin C trait) and beta thalassemia. Thalassemia can present as hemoglobin S (HbS) thalassemia or S-beta thalassemia (SThal) disease.

Systemic disease is most common with Hb SS, occurs less frequently in Hb SThal and Hb SC, and is exceedingly rare with Hb AS. Patients with Hb SC and Hb SThal are more likely to have retinal complications from sickle-cell disease.1

Hb SE, a type of beta-thalassemic hemoglobinopathy, is found predominantly among Southeast Asians. Although our patient did not appear to be of Asian descent, he is from the Caribbean, where there is a large Asian population on some of the islands. In HbE, anemia is either absent or very mild.1 HbE is a type of thalassemic anemia, which probably explains the retinal findings and why this patient was not aware that he had SC disease.

|

| 4. Inferotemporal portion of the left eye shows areas of fibrous proliferation. |

Several ocular complications are associated with sickle cell anemia. Most of these are mild and can go unrecognized. They are grouped as:

Nonproliferative manifestations. More common nonproliferative changes include alterations in the conjunctival vasculature, iris atrophy and salmon-patch hemorrhages. The latter results from a blowout in the vascular wall, which has been weakened by prior episodes of occlusion and ischemia. Retinal iridescent spots form after resorption of the salmon patch hemorrhages. Black sunbursts form due to migration of hyperplastic retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

Other nonproliferative changes include angioid streaks, choroidal occlusions and vascular changes in the optic nerve.

Proliferative sickle cell retinopathy. This develops due to arteriolar occlusions within the peripheral retina that result in localized ischemia. This ischemia leads to the production of vascular growth factors.

The end result: development of sea fan-shaped areas of neovascularization fronds. These sea fans can develop vitreous hemorrhage, which may lead to the formation of tractional vitreous membranes and finally, tractional and/or rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. The sea fans spontaneously autoinfarct on their own in as many as 60% of cases, resulting in localized areas of fibrous proliferation.2

Indications for treatment of proliferative sickle cell retinopathy are not always clear because the sea fans often resolve spontaneously. Because progression of the retinopathy and sea fans is slow, observation is often recommended. Laser photocoagulation may be indicated in patients who have recurrent vitreous hemorrhage, bilateral disease or large sea fans. Options include targeted feeder vessel photocoagulation and scatter photocoagulation.

We observed the two active sea fans in this patient and an area of fibrous proliferation from autoinfarcted sea fans. A diffuse vitreous hemorrhage was responsible for his blurred vision.

We initially chose to observe the patient. Three months later, he developed a tractional retinal detachment and required a segmental scleral buckle. He also underwent scatter laser photocoagulation to the areas of the sea fans. The sea fans resolved, and visual acuity returned to 20/20. He eventually developed proliferative sickle cell retinopathy O.S., but surgical intervention has not yet been necessary.

Retina Quiz Answers: 1) c; 2) b; 3) c; 4) d; 5) a.

1. Embury SH. Sickle cell anemia and associated hemoglobinopathies. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, Cecil Textbook of Medicine. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2004:1030.

2. Harlan JB, Fekrat S, Lutty GA, Goldberg MF. Hemoglobinopathies. In: Ryan SJ. Schachat AP, Murphy RP, eds. Retina, Vol. IIMedical Retina. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2000:1454-71.