Macular edema is a common cause of vision loss in several retinal disorders such as vein occlusion, diabetic retinopathy, and idiopathic and post-surgical cystoid macular edema. However, intravitreal injections of Kenalog (triamcinolone acetonide), a steroidal agent, appear effective in reducing macular edema and improving visual acuity in these conditions. Kenalog also has shown dramatic, though temporary, improvement in patients with refractory macular edema that resisted previous treatments.1

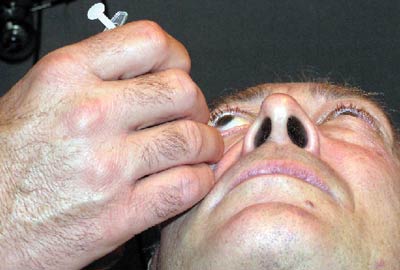

The intravitreal injection.

Limitations of Thermal Laser Therapies

The Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) demonstrated that focal thermal laser photocoagulation can effectively reduce the risk of moderate vision loss in patients with clinically significant macular edema (CSME) in which fluorescein angiography clearly delineated diabetic leakage.

However, in cases where diffuse diabetic leakage is present without an angiographically identified nidus for the edema, grid laser photocoagulation is typically employed. Unfortunately, this type of photocoagulation treatment has not been proven to be as effective as focal laser photocoagulation.2

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is a common retinal vascular disorder that can lead to significant visual disability. Macular edema is the major cause of decreased vision in these patients. The Central Vein Occlusion Study evaluated the efficacy of macular grid laser in patients with macular edema.3 While thermal laser photocoagulation reduced the amount of macular edema seen on angiography, it did not result in a significant improvement in visual function. Thus, study results discourage this treatment. There is currently no effective laser management for macular edema secondary to central vein occlusion.

A New Possibility?

In the quest for new treatment options, recent research has looked at intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Published results have shown that triamcinolone acetonide injections for CME associated with CRVO are effective at resolving the edema, and that there is corresponding improvement in visual acuity.4

Researchers injected 10 eyes with non-ischemic CRVO with 4mg in 0.1ml of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide. The mean time from diagnosis to treatment was 15.4 months. Visual acuity improved in all 10 eyes, and ocular coherence tomography demonstrated corresponding improvement in edema. Some 30% of eyes without a history of glaucoma required topical aqueous suppressants following the treatment. One eye with a previous history of primary open-angle glaucoma required a trabeculectomy. There were no other reported side effects or complications in this study. Intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide has shown great promise in reducing cystoid macular edema from central vein occlusions.

|

| The injection materials |

In published case reports, clinicians reported a prompt anatomical and functional improvement in a patient with macular edema secondary to nonischemic CRVO after intravitreal triamcinolone injection.5 Specifically, visual acuity improved from 20/20 to 20/25 in one month following treatment. This improvement correlated with reduction of central foveal thickness as demonstrated by OCT.

By contrast, the patient with ischemic CRVO achieved significant but temporary anatomic benefit from intravitreal steroid injection. Visual improvement in this patient was not as dramatic as in the patient with non-ischemic CRVO, and required repeat injections. It was hypothesized that the increased severity of ischemic CRVO accounted for the differences in outcome. The authors of the report believe that one injection of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide that lasts three months may be sufficient for nonischemic vein occlusions but not for ischemic central vein occlusions. Though this publication is a small sample of retrospective case studies, intravitreal Kenalog injections show promise for effectively managing CRVO complicated by macular edema.

Diabetic Macular Edema

Since results of ETDRS became available, focal argon laser has been the gold standard for treating diabetic macular edema resulting from angiographically identifiable leaking microaneurysms. However, when angiography does not reveal the source for diffuse macular edema, laser treatment cannot be focused on specific areas of retinal leakage. The efficacy of grid laser treatment, which scatters fine laser coagulation spots throughout the macular region, has been controversial and not yet proven.6

These uncertainties in the management of diabetic macular edema have paved the way for alternative treatment options, such as intravitreal triamcinolone injections. Clinical case studies have shown that 25mg of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide improves visual acuity in patients with diffuse diabetic macular edema.6

Intravitreal triamcinolone injection may also be useful where focal laser has failed.6,7 Eyes with persistent macular edema previously treated with two sessions of laser photocoagulation were offered intravitreal triamcinolone at least six months after initial treatment. Mean improvement in visual acuity measured 2.4, 2.4 and 1.3 Snellen lines at one, three and six months post-injection, respectively. Central macular thickness, as measured by OCT, decreased by 55%, 57.5% and 38%, respectively, over the same intervals.7

The Steroids

Triamcinolone acetonide is a corticosteroid that has been used for years to treat conditions such as uveitis and chalazion. Two other corticosteroids, Depro-Medrol (methylprednisolone acetate) and Celestone Soluspan (betamethasone sodium phosphate) produce intense retinal degeneration, lens damage (within 24 hours) and pre-retinal membrane formation in their standard concentrations when injected intravitreally.4,8 These toxic effects are believed to be caused by the preservatives or the inadequate osmolarity of the vehicles themselves.8 In contrast, studies that compared 1mg of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide to saline injections in rabbit eyes did not demonstrate ocular toxicity.9

The mechanism of action of triamcinolone acetonide appears to be through reducing the breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier through the non-specific blockade of the arachidonic acid pathway, or down regulating vascular endothelial growth factor.5 The duration of effect of a single intravitreal injection ranges from two to nine months, with the average expected to last about three months.10-12 Low, but measurable, intraocular concentrations have been documented for up to 1.5 years after application.12

The Technique

The technique may vary slightly depending upon the individual doctor. The procedure is often performed in a reclined examination chair in the office.

The most common technique involves cleaning the lids and lashes with a 10% povidone-iodine solution after anesthetizing the eye with proparacaine. One to three drops of iodine may also be placed in the cul-de-sac of the eye. An alternative to this would be to instill two drops of a fluoroquinolone antibiotic, separated by five minutes. Gentle pressure is often applied prior to injection in order to allow more room for the space occupying material. A lid speculum may be used to secure the lids if necessary and either a proparacaine swab is applied to the conjunctiva for one minute or a subconjunctival injection of xylocaine is performed at the injection site.

The material is a thick suspension and needs to be shaken well prior to withdrawal from the vial and cannot be left in the syringe for long as it will coalesce. An injection of 4mg/0.1ml triamcinolone acetonide is administered through the pars plana (about 1mm from the limbus) with a 27 or 30 gauge needle. After injection, inspect the vitreous for the presence of the drug, which will appear as a white ball of material. The intraocular pressure will rise immediately secondary to the space occupied by the injected material, but will normalize within an hour. Some physicians will prophylactically prescribe aqueous suppressants and fluoroquinolone antibiotics for the first week after the injection.

Reappoint the patient within one to two weeks to measure intraocular pressure and rule out endophthalmitis. The corticosteroid may be visible in the vitreous cavity for up to six weeks, gradually diminishing over that period of time. Material injected into the anterior vitreous may get caught in the aqueous convection current and accumulate in the anterior chamber, where it may appear similar to a hypopyon and mimic endophthalmitis.

Immediately following the procedure, the patient may have a sub-conjunctival hemorrhage at the injection site. The patient will see a large floater or obstruction in his or her vision due to the presence of the drug; reassure the patient that this will gradually resolve over a period of up to three weeks as it shrinks and settles inferiorly.

|

|

| Subconjunctival injection of xylocaine at injection site. |

Complications

Potential complications of intravitreal triamcinolone injections include elevated intraocular pressure, cataract formation, and globe-threatening endophthalmitis.4 Complications such as choroidal hemorrhage and retinal detachment have also been reported, although these appear to be more a result of injection technique and not the medication itself.

Of the reported complications, elevated intraocular pressure is most common with the incidence ranging from 30 to 50% of patients receiving 4mg/0.1ml intravitreal triamcinolone injections.4,10,13,14 In one study, 48.8% of patients had an increase in intraocular pressure of 5mm Hg or greater, and 27.9% had an increase of 10mm Hg or greater. 13 The elevation occurred on average 4.1 weeks after injection with the maximum increase at 6.6 weeks. All eyes responded to topical glaucoma medications. In patients requiring additional injections, elevated intraocular pressure was shown if only after the first injection a rise occurred.13 The side effect of elevated pressure appears transient and resolves in time with intraocular dissipation of the medication.

The incidence of acute endophthalmitis appears to be less than 1%.15 Bacterial endophthalmitis may present in an atypical, delayed manner with decreased vision but without pain or redness.16 The presenting sign may be uveitis and hypopyon, which may be a sterile response or the steroid itself.17

In many cases, the condition resolves without treatment. In patients with ocular inflammation following injection and presumed infectious endophthalmitis, subsequent microbiologic studies failed to reveal the presence of any organisms and the inflammatory response resolved with improvement of visual acuity.18 Therefore, it may be appropriate to closely observe noninfectious endophthalmitis patients who have an absence of eye pain.

Vision loss from edematous macular conditions remains a significant problem. The mainstay of treatment for these conditions, thermal laser photocoagulation, carries the risk of tissue damage. Furthermore, many conditions are not amenable to laser therapy.

This has led to the advent of intravitreal steroid injection in an attempt to better manage macular edematous conditions and preserve vision. Recent research has demonstrated benefits from this new therapeutic approach and, in time, there should be clear indications as to the proper usage of intravitreal steroid injections for the management of edematous macular diseases.

Dr. Vollmer is an Instructor of Optometry at Nova Southeastern University in Ft. Lauderdale. Dr. Sowka is a Professor of Optometry at Nova Southeastern University. Special acknowledgements also go to Julio Perez, M.D., and Rena Cappelli, O.D.

- Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Rosenfeld PJ. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for idiopathic cystoid macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol 2003 Oct;136(4):737-9.

- Early photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 9. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology 1991 May;98(5 Suppl):766-85.

- Evaluation of grid pattern photocoagulation for macular edema in central vein occlusion. The Central Vein Occlusion Study Group M report. Ophthalmology 1995 Oct;102(10):1425-33.

- Park CH, Jaffe GJ, Fekrat S. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide in eyes with cystoid macular edema associated with central retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2003 Sep;136(3):419-25.

- Ip MS, Kumar KS. Intravitreous triamcinolone acetonide as treatment for macular edema from central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 2002 Sep;120(9):1217-9.

- Jonas JB, Kreissig I, Sofker A, Degenring RF. Intravitreal injection of triamcinolone for diffuse diabetic macular edema. Arch Ophthalmol 2003 Jan;121(1):57-61.

- Martidis, A, Duker JS, Greenberg PB, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2002 May;109(5):920-7.

- Hida T, Chandler D, Arena JE, Machemer R. Experimental and clinical observations of the intraocular toxicity of commercial corticosteroid preparations. Am J Ophthalmol 1986 Feb 15;101(2):190-5.

- McCuen BW 2nd, Bessler M, Tano Y, et al. The lack of toxicity of intravitreally administered triamcinolone acetonide. Am J Ophthalmol 1981 Jun;91(6):785-8.

- Jonas JB, Kreissig I, Degenring RF. Treatment of oedematous, proliferative and neovascular diseases by intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 2003 Jun;220(6):384-90.

- Beer PM, Bakri SJ, Singh RJ, et al. Intraocular concentration and pharmacokinetics of triamcinolone acetonide after a single intravitreal injection. Ophthalmology 2003 Apr;110(4):681-6.

- Jonas JB. Intraocular availability of triamcinolone acetonide after intravitreal injection. Am J Ophthalmol 2004 Mar;137(3):560-2.

- Bakri SJ, Beer PM. The effect of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide on intraocular pressure. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2003 Sep-Oct;34(5):386-90.

- Jonas JB, Kreissig I, Degenring R. Intraocular pressure after intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Br J Ophthalmol 2003 Jan;87(1):24-7.

- Moshfeghi DM, Kaiser PK, Scott IU, et al. Acute endophthalmitis following intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection. Am J Ophthalmol 2003 Nov;136(5):791-6.

- Nelson ML, Tennant MT, Sivalingam A, et al. Infectious and presumed noninfectious endophthalmitis after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection. Retina 2003 Oct;23(5):686-91.

- Roth DB, Chieh J, Spirn MJ, et al. Noninfectious endophthalmitis associated with intravitreal triamcinolone injection. Arch Ophthalmol 2003 Sep;121(9):1279-82.

- Benhamou N, Massin P, Haouchine B, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory pseudophakic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol 2003 Feb;135(2):246-9.