|

A 40-year-old male presented complaining of progressive swelling of his right eye. An ophthalmologist saw him one week prior and gave him unknown drops; however, his swelling continued to worsen. A different ophthalmologist then diagnosed him with epidemic keratoconjunctivits (EKC) and started him on Tobradex (tobramycin/dexamethasone, Alcon) drops and erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. His swelling progressed even further, which prompted him to go to the emergency department. He denied any double vision, pain or blurry vision.

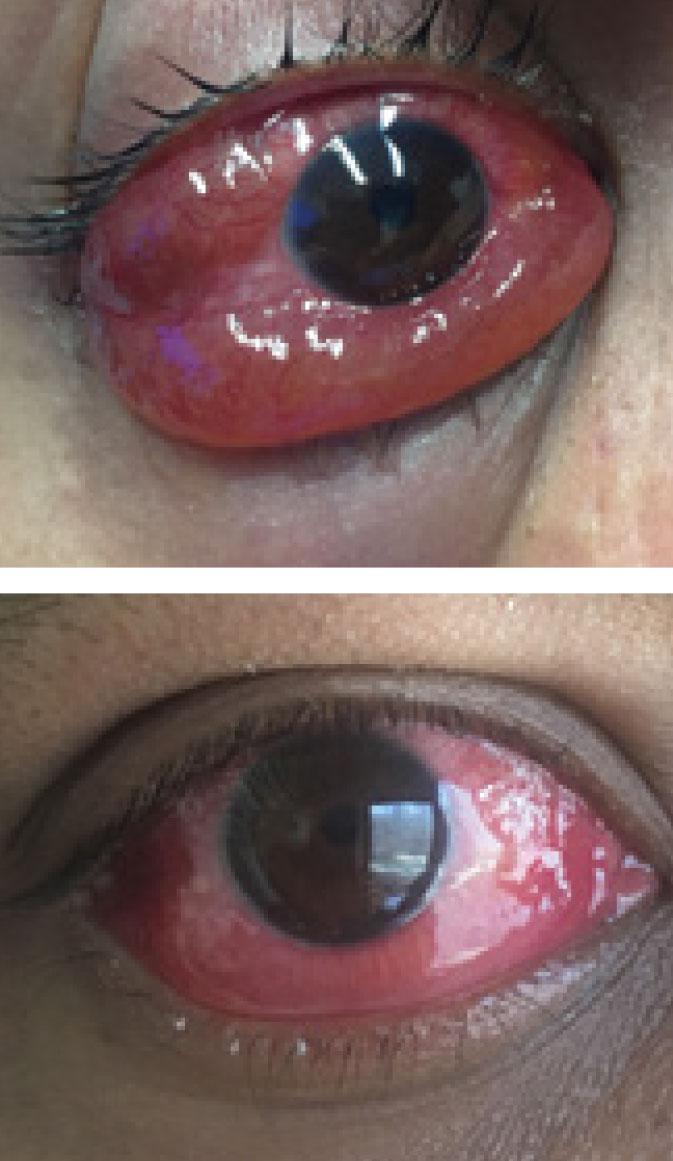

On exam, his visual acuity was 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS. No afferent pupillary defect was noted and his intraocular pressures via Tonopen (Reichert) were 11mm Hg OD and 12mm Hg OS. There was marked swelling and chemosis of the right eye. There was lateral restriction of his ocular motility on the right eye, and, although he did not report diplopia during the initial history, he reported seeing two images when instructed to look to the right. Other than the swelling and reduced ocular motility, the rest of his exam was unremarkable. There was no retinal abnormality noted and no disc edema was present.

|

| One dose of prednisone led to significant improvement of the patient’s injection and severe chemosis of the right eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Guessing Game

The initial differential list included: idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI), thyroid associated orbitopathy (TAO), orbital lymphoma, orbital cellulits, carotid cavernous fistula and EKC. His lack of pain made orbital cellulitis unlikely, and the degree of swelling made EKC unlikely; however, they were still considered in the initial differential list. A complete blood count (CBC) was ordered along with computed tomography CT of his orbits and CT angiography (CTA) of his brain. His CBC and CTA were unremarkable. The orbital CT demonstrated enlargement of the right lacrimal gland and right lateral rectus muscle with proptosis. There appeared to be swelling of both the belly and tendinous insertion of the lateral rectus.

After reviewing his imaging, orbital cellulitis, carotid cavernous fistula and EKC were excluded from the differentials. Additionally, because both the lateral rectus muscle belly and tendon were enlarged, TAO was unlikely to be the cause. Lastly, granulomatosis with polyangiitis and sarcoidosis can rarely affect the extraocular muscles (EOMs) and lacrimal gland, so serology studies for these disorders were ordered and were negative.

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation and CT findings were most consistent with IOI, and the patient was given 80mg of prednisone and instructed to follow up 24 hours later.

On exam the following day, there was significant improvement of the chemosis. Given the rapid response to just one dose of prednisone, IOI continued to seem the most likely diagnosis. The patient was instructed to continue 80mg of prednisone for three more days then cut to 60mg daily. On follow up one week later, he showed continued improvement of the eye swelling. The EOM restriction had resolved, and he did not notice the diplopia when looking to the right anymore. I slowly tapered the prednisone over the next six weeks, dropping 10mg each week.

On follow-up after he finished the prednisone taper, his clinical exam was completely normal with no proptosis, EOM restriction, chemosis or diplopia. As of his last exam, four months after finishing the prednisone, there was no recurrence.

|

| CT findings revealed swelling of right lateral rectus muscle and lacrimal gland, which helped narrow down the diagnosis to IOI. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

IOI is a noninfectious, inflammatory disorder of the orbit without any identifiable local or systemic cause.1-4 The syndrome can be categorized depending on which structure(s) are involved: myositis, dacryoadenitis, anterior, apical or diffuse inflammation.3 Rarer types of IOI include periscleritis and perineuritis.4

Anterior IOI causes inflammation of the globe, conjunctiva and eyelids generally without proptosis, while diffuse IOI affects the same structures but tends to be more severe and more often seen with proptosis.4 Myositis involves single or multiple EOMs where the medial rectus is most commonly affected, followed by the superior, lateral and inferior rectus muscles.4

Dacryoadenitis is the most common subtype of IOI and causes inflammation of the lacrimal gland. With apical IOI, inflammation of the orbital apex is seen, which can spread intracranially affecting the cavernous sinus and middle cranial fossa.4 Lastly, periscleritis involves inflammation of the scleral, uvea or tenon’s capsue. Perineuritis is defined by inflammation of the optic nerve sheath. This is in contrast to optic neuritis, which affects the axons of the nerve.4

In general, the presenting symptoms of IOI include pain, periorbital edema, chemosis, proptosis, diplopia and reduced vision. It is typically a unilateral disease with only rare bilateral involvement. Diagnosing IOI can be challenging, as there can be similarities between IOI, TAO and orbital lymphoma. Certain features, however, can help to distinguish them from one another. With IOI myositis, both the muscle belly and tendon tend to be inflamed, as seen in this patient, in contrast to TAO, where only the muscle belly is involved and the tendinous insertion is typically spared.

Also, TAO most commonly affects the inferior followed by the medial and then the superior rectus. Isolated lateral rectus muscle involvement as seen in this patient is extremely rare for thyroid orbitopathy. Additionally, IOI is commonly unilateral where TAO is usually bilateral. Lastly, TAO is generally unresponsive to steroid therapy—which wasn’t the case in treating this patient.

Orbital lymphoma can also be difficult to differentiate from IOI; however, this patient’s dramatic response to just one dose of prednisone with no recurrence since stopping treatment makes that an unlikely scenario. A biopsy isn’t indicated initially if the suspicion for IOI is high, but it is necessary if there is a higher suspicion for another etiology or if patients aren’t improving on steroid treatment. Serology studies testing can also be helpful to role out orbital sarcoidosis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Treatment

IOI treatment largely involves oral steroids, and more than 75% of patients show significant improvement within 24 to 48 hours.4 An initial dose of 1mg/kg/day to 2mg/kg/day is recommended, and I almost always start with 80mg to 100mg per day. A slow taper, generally over six to eight weeks, is necessary to prevent a flare up of the inflammation. For patients who don’t respond to oral steroids, radiotherapy, antimetabolies, T-cell inhibitors, alkylating agents, lymphocyte inhibitors and TNF-alpha inhibitors have all been reported as alternatives.4

IOI can be a difficult syndrome to diagnose, especially early in its course. Treatment is largely successful with oral steroids, and patients typically respond quickly. Because biopsy can be difficult to obtain when the inflammation is deeper within the orbit, it isn’t always recommended initially. Differentiating IOI from other orbital disorders can take some experience, but certain radiologic, serologic and clinical differences aid the diagnosis.

1. Jacob MK. Idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2012;5(2):124-5. 2. Kamili, MA, G A, Dar IH, et al. Orbital pseudotumor. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2009;2(2):96-9. 3. Chaudhry IA, Shamsi FA, Arat YO, Riley FC. Orbital pseudotumor: Distinct diagnostic features and management. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2008;15(1):17-7. 4. Yesiltas YS, Gündüz AK. Idiopathic orbital inflammation: review of literature and new advances. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2018;25(2):71-80. |