|

In February 2015, an 86-year-old white female presented on an urgent basis referred from a local urgent care center due to the possibility of zoster, with a note of “blisters” on the eyelid. She had been to the urgent care center the previous day with complaints of blurred vision in the right eye as well as periocular pain on the right side.

The patient was in no acute distress. She complained of intermittent pain and redness in and around the right eye for the past couple of weeks. She mentioned that she had received the shingles vaccine about two years earlier. She denied any photopsia.

The last time I saw her in my office was in 2012, and she was lost to follow up until this presentation. What initially brought her into the urgent care center was the discomfort in her right eye, which she described as a dull, non-stabbing pain that had worsened in the past three days.

Current medications included omeprazole QD, metoprolol QD and an unknown Rx sleep aid HS. She had no allergies to medications.

Diagnostic Data

Her visual acuity was hand motions at three feet in her right eye, 20/40 in her left, neither improving with pinhole. She displayed an equivocal afferent pupillary defect in the right eye, with both pupils sluggishly reacting to light. Extraocular motilities were full in all positions of gaze.

| |

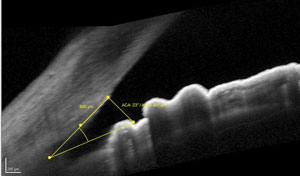

| Gonioscopy could not confirm neovascularization in the angle, although OCT shows that it is open. The question remains whether a vascularization is present. |

Slit lamp examination of the anterior segment was remarkable for several items. Of minimal significance was mild blepharitis and dermatochalasis in both eyes. The cornea in the right eye was mildly hazy, with moderate striate keratopathy and guttatae. The cornea of the left was clear, except for a symmetric presentation of the guttatae. Examination of the anterior chambers—specifically looking for cells and flare—was difficult in the right eye because of the corneal haze, so no cells were appreciated; the left anterior chamber was unremarkable. Iris details were also somewhat obscured in the right eye, and were normal in the left. The right eye also showed moderate episcleral injection.

Intraocular pressure measured 42mm Hg OD and 26mm Hg OS at 2:15 PM. Angles appeared to be open by Van Herick estimation.

Upon dilation, her crystalline lenses were characterized by 2+ anterior and posterior cortical cataracts, 3+ nuclear cataracts and mild posterior subcapsular haze in both eyes. The posterior cortical cataract in the right eye was on the visual axis; that of the left eye was off the visual axis.

Her cup-to-disc ratios were 0.35 x 0.35 OD and 0.20 x 0.20 OS. Disc margins were distinct, although the right was somewhat hyperemic, and fine details were difficult to ascertain due to the media opacities in that eye.

Both maculae were characterized by retinal pigment epithelial granulation and drusen, consistent with mild nonangiogenic age-related macular degeneration. But the significant finding in the right eye was a central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) with what appeared to be resorbing intraretinal hemorrhages in all quadrants. The retinal vasculature was characterized by moderate arteriolar sclerotic retinopathy in both eyes, clearly discernable in the left eye. The retinal venules were moderately tortuous OD>OS. Peripheral retinal evaluation was unremarkable OU.

| |

| While difficult to see by gonioscopy, our patient had neovascularization of the angle, as seen in this similar patient. Photo: Greg Black, OD, and Julie Tyler, OD. |

Upon gonioscopic examination, details of the angle anatomy in the right eye were obscured by the hazy cornea. In the left eye, the angle was normal and open. Anterior segment OCT imaging confirmed the presence of open angles in both eyes.

OCT evaluation of the macula was unremarkable in the left eye, but the right was consistent with macular edema associated with the CRVO. Lastly, I took fundus photos to document the state of the CRVO at this initial presentation.

Diagnosis

The patient’s right eye certainly has a CRVO of unknown duration, associated macular edema and significantly elevated IOP, OD>OS. The elevated IOP was very likely the source of her intermittent pain in the right eye. She had no evidence of an active outbreak of herpes zoster.

Management and Discussion

Elevated IOP can induce a CRVO. Also, one of the sequelae of long-standing CRVO is the development of neovascularization of the posterior and anterior segments, and subsequently, due to neovascularization of the iris and anterior chamber angle, neovascular glaucoma. Because the media were not clear, neovascularization of neither the posterior segment nor anterior segment were visible. The quandary at this visit pertained to the presence of two distinct clinical entities, each of which can induce the other.

So which came first? Did the VO induce neovascularization and subsequent neovascular glaucoma? Or, did elevated IOP (of non-neovascular origin) induce the VO?

In preparing a management plan for this patient, multiple problems need to be sorted out; so, it’s the optometrist’s duty to direct the patient’s care with the help of other subspecialties. It’s important to also include evaluations that may in fact help shed light on the ultimate cause of these two problems. Obviously, IOP needs to be lowered, not only to reduce the likelihood of neuro-retinal rim damage, but also to mitigate the role that IOP may have had in inducing the VO. Given the macular edema associated with the VO, a retinal consult is in order, but not necessarily specifically for the reduction of the macular edema. On the contrary, a retinal consult was ordered primarily to obtain a fluorescein angiogram (FA) to help determine whether an occult retinal neovascularization was present. The presence of neovascularization of the retina can be a good indicator that the underlying etiology of the elevated IOP is, in fact, sequelae from the neovascularization due to retinal hypoxia.

At the completion of the initial visit, we scheduled the patient for a fluorescein angiogram, and I prescribed Lumigan (bimatoprost 0.01%, Allergan) HS OD as well as Alphagan P (brimonidine 0.1%, Allergan) BID OD.

When the patient returned for follow up, she was still in as much pain, but her IOP now measured 44mm Hg OD and 25mm Hg OS. Obviously, the IOP-lowering agents were having little effect, so the likelihood that her ocular hypertension was neovascular in origin seemed more plausible. The patient’s FA was scheduled the following day, so I did not make any changes in her medications pending the results.

Sure enough, the FA revealed occult neovascularization of the retina, and possible anterior segment late fluorescein staining was noted.

In light of the FA findings, and given that the IOP-lowering agents had no effect, we can safely assume that we are dealing with neovascular glaucoma. To answer the original question—which came first?— the vein occlusion was probably the precipitating factor that led to the patient’s current constellation of problems.

But there are a few other items that were put on the back burner until the clinical picture became clearer, and now need to be dealt with. One is her rather dense cataracts. The other is establishing the etiology of the VO in the first place as these are often associated with elevated blood pressure, elevated cholesterol and diabetes. This of course is managed by the patient’s primary health care provider, and I’ve contacted him for consultation.

The retinal specialist, whose view in the right eye was likewise limited, felt that the cataract in that eye should be removed prior to performing panretinal photocoagulation (PRP). My opinion was that the patient would be best served if the cataract surgery was performed by a glaucoma surgeon comfortable in lens extractions.

Ultimately, after consultation with a glaucoma surgeon, the current plan is to proceed with lens extraction with IOL in the right eye, with the combination of Ahmed valve implantation at the same time (to facilitate quicker IOP reduction and better long-term IOP stability), followed shortly by PRP.

For now, the patient is continuing with follow-up visits here. In such cases, the optometrist must maintain visits with these patients during surgical interventions. After all, the patient will return to the OD for long-term care, so it’s critical that the optometrist be involved with all aspects of the perioperative care.