|

There’s no avoiding the glaucoma patients and suspects who, for whatever reason, do not comply with follow-up care and visits. When they do eventually return to the office, most of the time their condition has worsened and your work is much harder. Oddly enough, for one of my recent patients, the opposite was true.

|

|

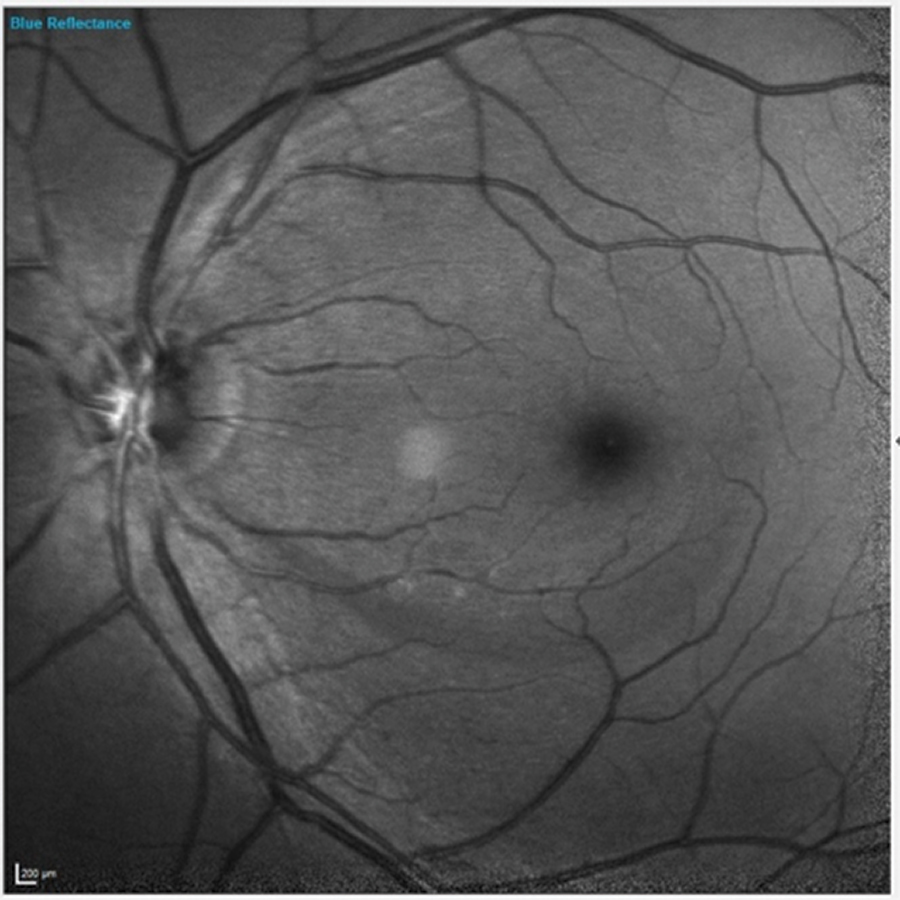

Fig. 1. Note the inferior wedge defect clearly visible in the patient’s left eye. Click image to enlarge. |

The Case

In 2016, a 66-year-old Caucasian male presented as a new patient. It had been about eight years since he had last seen an eye specialist. He reported gradually decreasing vision in both eyes that involved both distance and near. His medications included lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, Lipitor (atorvastatin calcium, Pfizer), famotidine, metformin, Cialis (tadalafil, Eli Lilly) and 81mg acetylsalicylic acid, and he reported no allergies to medications.

|

|

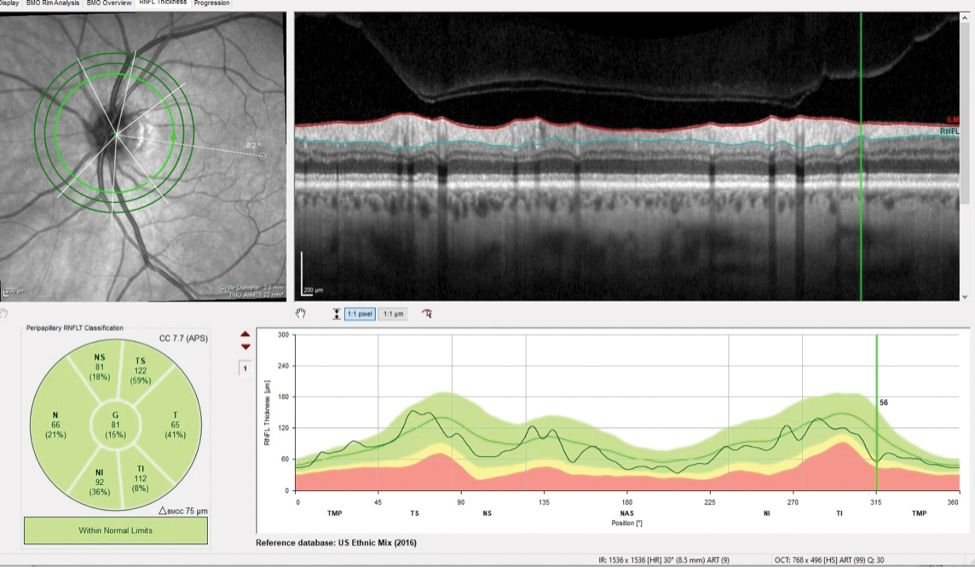

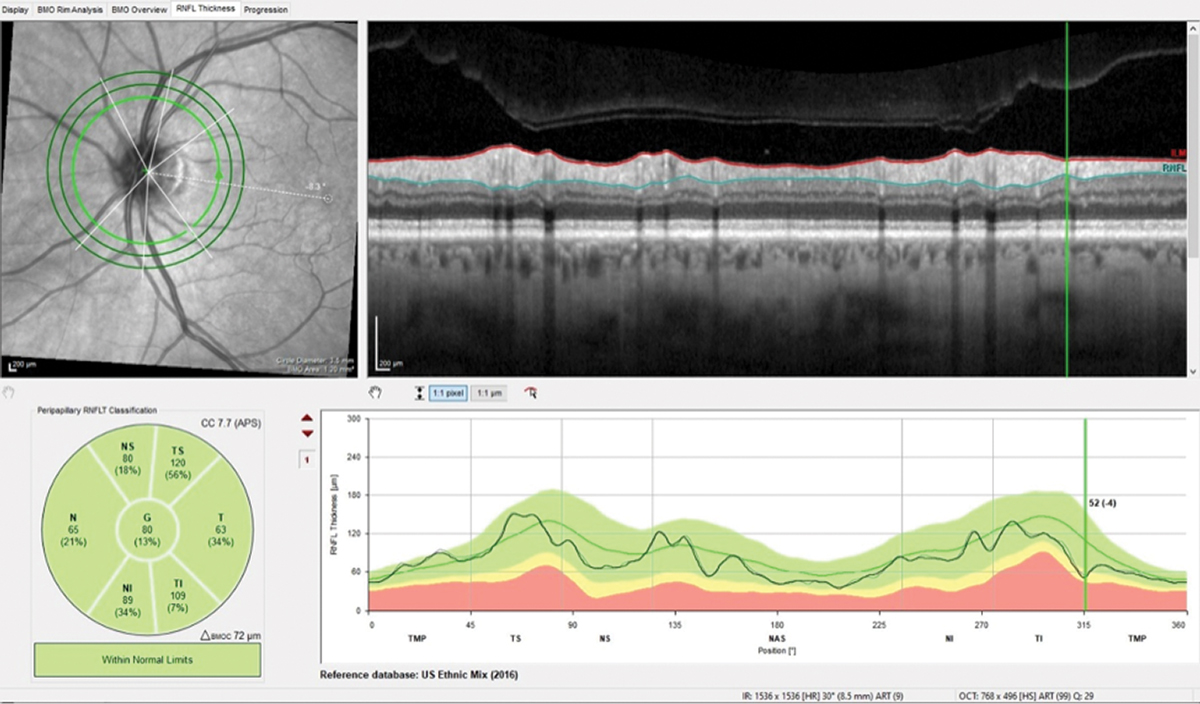

Fig. 2. The patient’s inferotemporally thinned RNFL in the area of the wedge defect measured 56µm. Click image to enlarge. |

The patient’s entering visual acuities were 20/40 OD and 20/30- OS, and his best-corrected visual acuities through hyperopic astigmatic and presbyopic correction were 20/20- OD and 20/25+ OS. His pupils were equal, round and reactive to light and accommodation, with no afferent pupillary defect, and his extraocular muscles were full in all positions of gaze.

Slit lamp examination of the anterior segment was essentially unremarkable. The patient’s applanation tensions were 18mm Hg OD and 19mm Hg OS.

Through dilated pupils, the patient’s crystalline lenses were characterized by early nuclear sclerosis bilaterally and cortical spokes in the anterior cortex outside of the visual axis. His optic nerves were characterized by cup-to-disc ratios of 0.3/0.3 OD and OS. The neuroretinal rims were plush and well-perfused.

The patient’s retinal vascular examination revealed mild arteriolarsclerotic retinopathy and venular dilation consistent with well-controlled type two diabetes. His last HbA1c was 6.2, which was obtained about four months prior. There was no evidence of neovascularization or diabetic macular edema in either eye. Both maculae had age-consistent retinal pigment epithelium granulation. Bilateral posterior vitreous detachment was present, and the peripheral retinal evaluation was normal OU.

|

|

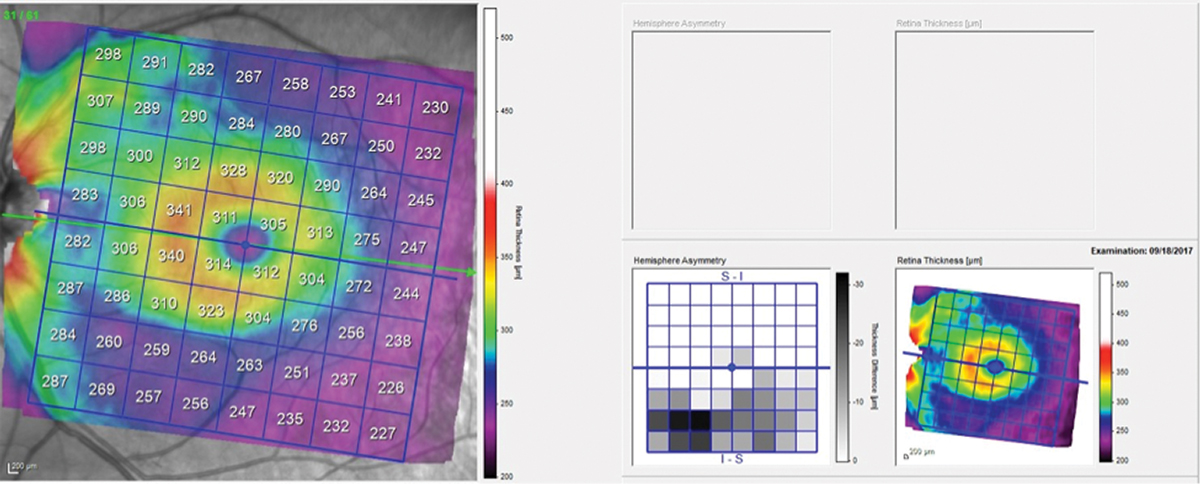

Fig. 3. Total retinal thickness in the left macula shows asymmetry between the superior and inferior hemispheres, with the inferior hemisphere thinner in the area of the wedge defect. Click image to enlarge. |

Of interest in the patient’s left eye was a clearly visible retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) wedge defect originating inferiorly just temporal to the foveal avascular zone and extending to the optic nerve (Figure 1). The wedge defect was consistent with those often seen in glaucoma. But similar wedge defects are also seen in focal anterior retinal vascular problems, such as severe arteriolar stenosis. A closer look at the vasculature in this area did not raise any red flags to indicate that this wedge defect was of vascular origin.

Given the lack of a suggested vascular etiology, the question turned into whether the wedge defect was associated with early-onset glaucoma, as the optic nerve was normal in appearance and the neuroretinal rim did not appear to be compromised. Accordingly, I asked the patient to return for further evaluation.

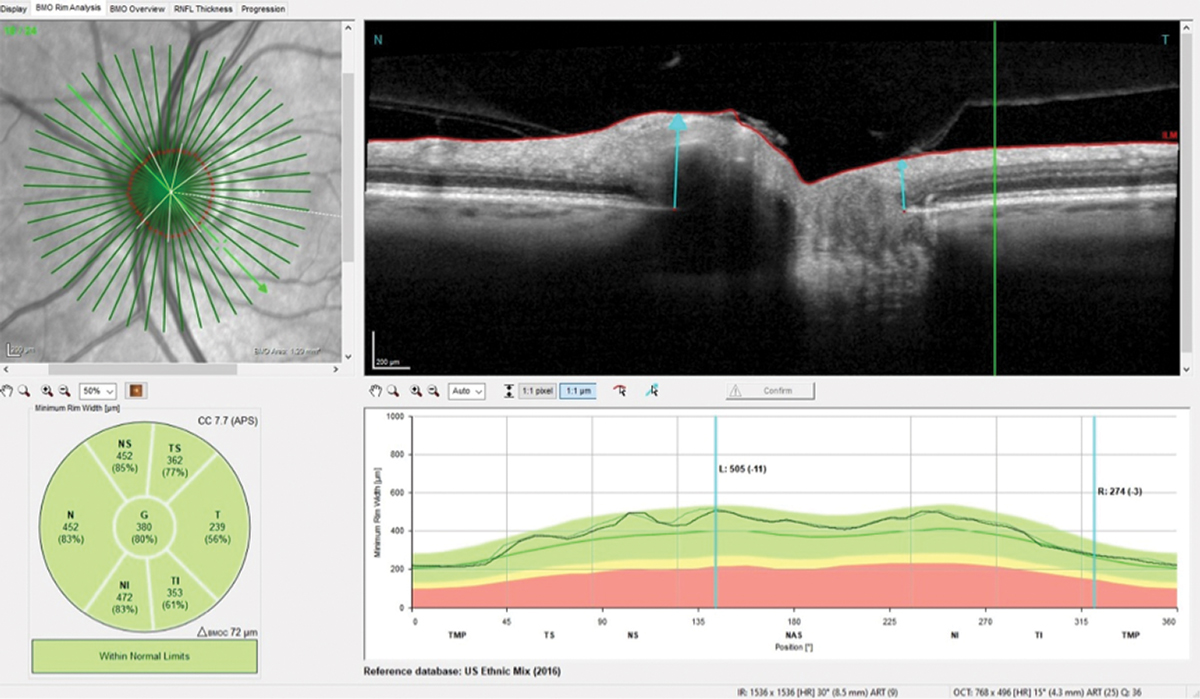

The patient presented about three weeks later, at which point his intraocular pressures were essentially the same. His pachymetry readings were 566µm OD and 549µm OS. Perioptic RNFL scans of the left eye demonstrated a depression in the area of the wedge defect OS (Figure 2). The macular scan also showed hemispheric asymmetry in the area of the wedge defect (Figure 3). The Bruch’s membrane opening minimum rim width (BMO-MRW) scan had a normal appearance, indicating that the wedge defect did not extend into the neuroretinal rim. The clinical appearance as seen in vivo confirmed this finding.

|

|

Fig. 4. Note the difference of only 4µm in the wedge defect and overall stability in this follow-up scan of the perioptic RNFL. Click image to enlarge. |

There was not enough firm evidence at this time that the patient did, in fact, have glaucoma, but he did need close monitoring. I scheduled a threshold field test for a month out, but he was a no-show. He was lost to follow-up until this past August, at which point he returned with complaints of gradually decreasing vision OU. I anticipated that his cataracts had progressed (they had) and was worried that he had developed frank glaucoma in the interim.

Surprisingly, repeat imaging of the perioptic RNFL, the macula and the BMO-MRW did not indicate any significant changes over the four-year period (Figures 4 and 5). Funduscopically, the wedge defect was still present but did not appear to have enlarged. This certainly made my life easier, as no change meant no conversion to glaucoma. This was not what I was expecting and was a rare surprise. I asked the patient to return in a year. Will he show up this time? I’ll let you know in a year.

Discussion

One of the hallmark structural signs of glaucoma is change that worsens over time. With the advances in OCT technology that we’ve experienced over the past several years, determining this change is now much easier, improving the quality of glaucoma care for our patients.

|

|

Fig. 5. The neuroretinal rim remained stable compared with baseline despite the four years the patient was lost to follow-up. Click image to enlarge. |

It’s incumbent that we as clinicians obtain quality baseline measurements of areas susceptible to glaucomatous damage so that we have a point of comparison. It’s necessary to obtain baseline scans in all three areas where glaucomatous damage can occur, namely the neuroretinal rim, circumpapillary RNFL and macula. In reality, while damage can be seen in any or all of these areas, we really don’t know exactly where the damage initially presents and progresses from. It may be that damage occurs initially in different locations depending on patient-specific characteristics.

While there are many pieces to the glaucoma puzzle, structurally there are only two scenarios: stability or progression. Glaucoma does not get better; loss of the neuroretinal rim tissue of ganglion cells does not reverse and regenerate. Taking advantage of the technology we have at our disposal is our best chance of pinpointing which situation we’re dealing with.