Because conjunctival lymphomas present with redness and swelling, they are easy to misdiagnose as inflammatory conditions, such as allergic eye disease or non-specific conjunctivitis. While malignant tumors of the conjunctiva are relatively rare compared to other cancers of the eye, we must nevertheless consider some patients who present with an inflamed conjunctiva suspect for conjunctival lymphoma.

There are several lymphomas of the conjunctiva and ocular adnexa. (See Lymphoma: An Overview.) Here, we will profile low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. We will also review the symptoms of MALT, present cases of misdiagnosis and discuss appropriate treatment of patients who are diagnosed with MALT.

|

| The initial presentation of MALT lymphoma is mild generalized injection and swelling at the caruncle. |

MALT lymphomas are extra-nodal tumors; that is, tumors that originate at sites other than the lymph nodes and spleen. Also known as marginal zone lymphomas or extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphomas, MALT lymphomas can occur in various organ systems. These include the gastrointestinal tract, skin, lung, thyroid, salivary gland, breast and ocular adnexa (including the conjunctiva). Most MALT lymphomas originate from B cells, with the gastrointestinal tract as the most common tumor site.1

We describe these lymphomas as low grade or high grade, according to the tumors specific histological and cellular characteristics. Low-grade MALT tumors generally have a better prognosis than high-grade tumors.2,3 Low-grade tumors are usually indolent, and they tend to remain localized to the original site for long periods.4

One study evaluated more than 100 cases of ocular lymphoid proliferation and found that the site of involvement was useful in predicting prognosis. Specifically, conjunctival lesions were associated with a 20% incidence of extraocular lymphoma vs. lesions of the orbit and eyelid, which were associated with a 35% and 67% incidence, respectively.5 Still, other studies have failed to find a statistically significant correlation between tumor location and outcome.6,7

The stage of the lesion at initial presentation seems to correlate highly to the final outcome. Lesions that are diagnosed while still localized to the ocular tissues (stage I tumors) have a far more favorable prognosis than stage II, III or IV tumors, which spread to distant sites and display systemic involvement.6-9 High-grade tumors and those that arise from T cells rather than B cells are associated with higher morbidity and a poorer prognosis.1,10

|

Lymphoma: An Overview |

| Commonly, lymphomas are considered either Hodgkins lymphoma (also called Hodgkins disease) or non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Hodgkins disease comprises about 15% of all lymphoma diagnoses and typically affects patients before age 30.8 Non-Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL) is more commonly found in patients past age 60, but this varies with the specific type of NHL.8 Hodgkins is much more predictable in its clinical presentation in terms of the structures affected. Both Hodgkins and NHL affect lymph tissue (lymph nodes and spleen) and non-lymphoid tissue, although Hodgkins lymphoma does so less frequently than does NHL.12 Another general classification system for lymphomas is based upon the tissue from which the tumor originated. This system consists of two broad categories: nodal, made up of tumors that originate in the lymph nodes or the spleen, and extranodal, made up of tumors that originate at other sites.2,13 The nodal type comprises half to three-quarters of all lymphomas.8 Within these two broad categories are many subtypes of tumors. MALT is the most common subtype of conjunctival lymphoma (63 of 112 patients in one study, for instance).8 However, seven other subtypes statistically carry a relatively higher risk of morbidity, with a higher probability that systemic lymphoma is also present.2 These other subtypes are follicle center lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, plasmacytoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, hairy cell leukemia and T-cell lymphoma.K.R., A.E. |

Initial Presentation

MALT conjunctival lymphomas present as pink- to salmon-colored conjunctival masses or chemosis. Nearly half these tumors are located in the fornix. Most others occur in the midbulbar region. Less commonly, the limbus and caruncle are affected.11

Symptoms of MALT most often include a mass or irritation. Patients may also complain of redness, tearing, itching, irritation, photophobia, proptosis, pain, ptosis and diplopia. Sometimes, however, patients may not have any complaints at all.11,12

The differential diagnoses of MALT lymphoma of the conjunctiva include granulomatous disease (such as sarcoidosis or tuberculosis), giant papillary conjunctivitis, allergic eye disease, non-specific conjunctivitis, amyloidosis, adult inclusion conjunctivitis and keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Cause for Misdiagnosis

The biggest pitfall in managing patients who have conjunctival lymphomas is misdiagnosis. MALT lymphomas are not immune to this problem, as the medical literature demonstrates.

For instance, two cases of bilateral MALT lymphomas were initially diagnosed as allergic conjunctivitis. One patient presented with chronic discharge and pain O.U. The other presented with a four-month history of pain in both eyes. After both patients were unresponsive to therapy, a biopsy was taken. They were diagnosed with MALT conjunctival lymphoma.9

In another report of five MALT conjunctival lymphoma cases, one patient had previously been diagnosed with allergic conjunctivitis due to irritation, redness and discharge, while another patient was initially diagnosed with papillary conjunctivitis secondary to contact lens wear.13

In another case, a female patient presented with hyperplastic altera-tions, cystic structures, mild chemosis of the conjunctiva and bilateral swelling in the parotid glands. Sjgrens syndrome was initially suspected, but examination revealed marked conjunctival hyperplasia. A biopsy revealed low-grade MALT lymphoma.14

Finally, a patient presented with a three-month history of irritation and mucopurulent discharge in the left eye. Hypertrophic conjunctival changes were present in the left eye, while small conjunctival follicles were present in both eyes. Con-junctival swabs revealed a diagnosis of chlamydia in both eyes. Despite successful treatment of the chlamydia, the conjunctival changes persisted. A biopsy of the left eye revealed MALT lymphoma.15

|

Case Report: 38-Year-Old Female with MALT Lymphoma | |||||||

|

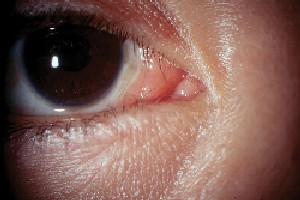

A 38-year-old Hispanic female presented complaining of a red growth in the corner of her right eye. She first noticed this growth about four months earlier. Upon examination, the condition appeared to be worsening and was associated with tearing and itching. Diagnostic Data

Her best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 O.D. and 20/15 O.S. Both pupils were reactive to light, and neither had an afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motility was full to all positions of gaze, and confrontation visual fields were full to finger counting in both eyes. Slit lamp examination of the right eye revealed a pink, swollen and chemotic bulbar conjunctiva. The findings extended 360 degrees, but were more marked in the caruncle and in the inferior bulbar region. The perilimbal area was relatively uninvolved. There was mild inflammation around the caruncle of her left eye as well, but the anterior segment of that eye was otherwise unremarkable. IOP measured 17mm Hg O.U. Dilated fundus evaluation showed a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.3/0.3 in both eyes with normal posterior poles and peripheral grounds. Based on the clinical appearance of her right eye, we diagnosed an allergic/toxic conjunctivitis and prescribed Acular (ketorolac tromethamine, Allergan) q3h O.D. and cold compresses, as needed, for relief of symptoms. At follow up, both three days and one week later, the patient reported a slight improvement in her symptoms, but the clinical findings were unchanged. We decided to keep her on the Acular for another two weeks, hoping that the clinical appearance would improve as well. We instructed the patient to return for follow-up two weeks later. Three weeks later, she returned and said that she felt the same as she had at her prior visit. The clinical presentation was unchanged. We switched her to Patanol (olopatadine, Alcon) b.i.d. O.D., and OTC Benadryl (diphenhydramine, Pfizer) at night to help control the inflammatory changes. We also instructed her to continue the cold compresses and return in two weeks.

At follow-up, the patient reported persistent variable redness from day to day and intermittent tearing. Clinical findings remained unchanged. We referred the patient for an ophthalmologic consult. She remained on the Patanol and Benadryl until she saw the M.D.

Diagnosis Treatment and Follow-up

About two years later, she presented with no signs of recurrence. However, dilation at this visit revealed fundus changes consistent with radiation retinopathy K.R., A.E. |

So, how can you avoid a misdiagnosis? Suspect conjunctival lym-phoma in any patient who has conjunctival inflammation, chemosis or erythema that is non-responsive to standard anti-infective and/or anti-inflammatory therapy within the expected time frame. Once you suspect ocular lymphoid proliferation, a prompt referral for a biopsy is indicated.

We cannot distinguish among the various types of lymphoid proliferation via slit lamp. However, histologic examination is highly accurate in accomplishing this.16 In the few cases that are histologically indeterminate, polymerase chain reaction analysis is often useful.7

Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis of MALT lympho-mas by the presence of:17

Centrocyte-like (CCL)cells.1,17 These cells are small to medium in size, with irregular nuclei and a moderate amount of cytoplasm.

Plasma cells in the subepithelium.1,18 These cells may have intranuclear inclusions or Dutcher bodies, but they are more commonly found in MALT tumors of non-conjunctival tissues.19,20

Follicular colonization. This is common in low-grade MALT lymphomas.17,21 This phenomenon is characterized by infiltration of reactive follicles by CCL cells, which then replace the follicles with neoplastic cells.

Lymphoepithelial lesions.1 These lesions occur when the mucosal surface is infiltrated by lymphoma cells that move to the space between the mucosal and glandular epithelium.

Once the biopsy confirms the diagnosis of conjunctival MALT lymphoma, patients should undergo a complete oncologic evaluation (also known as staging of the disease) to determine if systemic lymphoma is also present. This process generally includes a physical exam, laboratory testing and radiological evaluation of the chest and abdomen (X-ray, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging).2,13

|

FAST FACTS |

|

Conjunctival lymphomas are easy to misdiagnose as inflammatory conditions. MALT lymphomas are pink-to salmon-colored conjunctival masses or chemosis. Suspect conjunctival lymphoma in any patient with |

External beam radiation is the primary treatment for MALT lymphoma.22 The main side effects of radiotherapy include dry eye, cataract development, reduced visual acuity and radiation chorioretinopathy. Radiation retinopathy is characterized by a delayed-onset retinal occlusive vasculopathy that is slowly progressive and can lead to irreversible visual function.23

A recent study compared observation alone to radiation, with

favorable results for both groups. But, the conjunctival lesions in this study were resected to as great an extent as possible at the time of biopsy. So, the biopsy itself could be considered treatment by excision.24 Chemotherapy has been considered in cases of disseminated disease.

While the prognosis is generally quite good for patients with stage 1-type tumors, such as MALT, recurrences have been documented.25 Hence, long-term follow-up is required. (See Case Report: 38-Year-Old Female with MALT Lymphoma.) Still, most of these tumors are successfully removed with a single series of radiation treatments, and most patients remain alive and disease-free at long-term follow-up.2,10,19-22,25

Unfortunately, several ocular diseases can masquerade as other diagnoses. But, by educating ourselves about these diseases and the various cases of misdiagnoses, we can prevent further misdiagnosis and provide these and other patients with appropriate treatment at onset.

Dr. Reed is an associate professor of optometry at Nova Southeastern University College of Optometry in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. She teaches the course on Anterior Segment Ocular Disease, and is a clinical preceptor and the director of externships.

Dr. Espejo is an assistant professor of optometry at Nova South-eastern. She is module director in the Primary Care Clinic, and is actively involved in both externships and residency education.

1. Isaacson PG, Spencer J. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Histopathology 1987 May;11(5) :445-62.

2. Taal BG, Boot H, van Heerde P, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the stomach: endoscopic pattern and prognosis in low versus high-grade malignancy in relation to the MALT concept. Gut 1996 Oct;39(4):556-61.

3. Chan JK, Ng CS, Isaacson PG. Relationship between high-grade lymphoma and low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALToma) of the stomach. Am J Pathol 1990 May;136(5):1153-64.

4. Isaacson PG, Spencer J. The biology of low grade MALT lymphoma. J Clin Pathol 1995 May;48(5):395-7.

5. Knowles DM, Jakobiec FA, McNally L, Burke JS. Lymphoid hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma occurring in the ocular adnexa (orbit, conjunctiva, and eyelids): a prospective multiparametric analysis of 108 cases during 1977 to 1987. Hum Pathol 1990 Sep;21(9):959-73.

6. Auw-Haedrich C, Coupland SE, Kapp A, et al. Long term outcome of ocular adnexal lymphoma subtyped according to the REAL classification. Revised European and American Lymphoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2001 Jan;85(1):63-9.

7. Coupland SE, Krause L, Delecluse HJ, et al. Lymphoproliferative lesions of the ocular adnexa. Analysis of 112 cases. Ophthalmology 1998 Aug;105(8):1430-41.

8. Bierman P, Harris NL, Armitage JO. Non-Hodgkins Lymphomas. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil Textbook of Medicine. 22nd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1998: 1174-84.

9. Lee DH, Sohn HW, Park SH, Kang YK. Bilateral conjunctival mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma misdiagnosed as allergic conjunctivitis. Cornea 2001 May;20 (4) :427-9.

10. Hoang-Xuan T, Bodaghi B, Toublanc M, et al. Scleritis and mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: a new masquerade syndrome. Ophthalmology 1996 Apr;103

(4) :631-5.

11. Shields CL, Shields, JA, Carvalho C, et al. Conjunctival lymphoid tumors: clinical analysis of 117 cases and relationship to systemic lymphoma. Ophthalmology 2001 May;108 (5):979-84.

12. White WL, Ferry JA, Harris NL, Grove AS Jr. Ocular adnexal lymphoma. A clinicopathological study with identification of lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type. Ophthalmology 1995 Dec;102(12):1994-2006.

13. Hardman-Lea S, Kerr-Muir M, Wotherspoon AC, et al. Mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol 1994 Sep;112(9):1207-12.

14. Kurz-Levin MM, Flury R, Bernauer W. Diagnosis of MALT lymphoma by conjunctival biopsy: a case report. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1997 Sep;235(9):606-9.

15. Yeung L, Tsao YP, Chen PY, et al. Combination of adult inclusion conjunctivitis and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in a young adult. Cornea 2004 Jan;23(1):71-5.

16. Sharara N, Holden JT, Wojno TH, et al. Ocular adnexal lymphoid proliferations: clinical, histologic, flow cytometric, and molecular analysis of forty-three cases. Ophthalmology 2003 Jun;110(6):1245-54.

17. Mori N, Yatabe Y, Asai J. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Pathol Int 1995 Aug;45(8):544-51.

18. Wotherspoon AC. Choosing the right MALT. Gut 1996 Oct;39(4):617-8.

19. Bailey EM, Ferry JA, Harris NL, et al. Marginal zone lymphoma (low-grade B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type) of skin and subcutaneous tissue: a study of 15 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1996 Aug;20

(8):1011-23.

20. Wotherspoon AC, Diss TC, Pan LX, et al. Primary low-grade B-cell lymphoma of the conjunctiva: a mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type lymphoma. Histopathology 1993 Nov;23(5):417-24.

21. Isaacson PG, Androulakis-Papachristou A, Diss TC, et al. Follicular colonization in thyroid lymphoma. Am J Pathol 1992 Jul;141(1):43-52.

22. Heffler KF. Tumors of the cornea and conjunctiva. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1995 Aug;6(4):32-8.

23. Gunduz K, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Radiation retinopathy following plaque radiotherapy for posterior uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1999 May;117(5):609-14.

24. Matsuo T, Yoshino T. Long-term follow-up results of observation or radiation for conjunctival malignant melanoma. Ophthalmology 2004 Jun;111(6):1233-7.

25. Cahill MT, Moriarty PA, Kennedy SM. Conjunctival MALToma with systemic recurrence. Arch Ophthalmol 1998 Jan;116(1):97-9.