20th Annual Dry Eye ReportCheck out the other feature articles in this month's issue: |

For more than a decade, omega-3 fatty acid supplements have been hailed for their role in helping to alleviate dry eye symptoms with no significant side effects. While they’re not effective in every case and are typically used in conjunction with other methods, this avenue of care is pretty well-established. Then came the Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) study last May, which seemed to upend the validity of fish oil, as it found omega-3 fatty acids offered no benefit over the olive oil placebo.1

In light of these findings, should optometrists think about tossing omega-3 supplements from their dry eye treatment arsenals? Not so fast, caution some experts who suggest peeling back the layers of the study and taking a closer look before making up your mind.

“Be sure to read the scientific study, not just the headline and abstract, before making a decision on how to treat patients,” says Jeffrey Anshel, OD, of Encinitas, CA. “The protocol of a study must cover many bases and not be influenced by flaws in the design of the study. Also, no one study should represent the gold standard for treatment in any disease.”

Not everyone has taken the DREAM study with a grain of salt, however. According to Paul Karpecki, OD, of Lexington, KY, some doctors have stopped using fish oil altogether because of the results. He notes that those who had been on the fence about omega-3 supplements have now ruled them out as a dry eye treatment option and are wondering what neutraceuticals or other alternatives they should offer instead.

“Some people think the study results mean fish oil doesn’t work for dry eye, and that’s not the case,” Dr. Karpecki adds. “The fish oil treatment arm had a phenomenal statistical improvement from baseline. So, fish oil does work, and it’s very effective. But, why did the placebo arm work too?” It’s that parallel effect seen among the placebo group that has some doctors now questioning the role of omega-3 supplementation.

Meanwhile, the DREAM researchers stand by the study’s methodology and findings, and readily dispute the criticisms lobbed at the work.

In this article, experts in dry eye and ocular nutrition weigh in on the controversy.

|

| Click to enlarge image. Image: Getty Images |

Omega-3 Faces Scrutiny

The first mention of using omega-3 as a treatment for dry eye was in a 2005 study that showed women who ate regular amounts of tuna in their diets had lower rates of dry eye symptoms.2 It wasn’t until 2011, however, that a pilot study was specifically designed to determine if omega-3 would alleviate dry eye symptoms.3 The study concluded that dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids for dry eye had no significant effect on meibum lipid composition or aqueous tear evaporation rate.3 On the other hand, the average tear production and volume increased in the omega-3 group, as indicated by Schirmer testing and fluorophotometry.3 Dr. Anshel notes that many studies since have found that omega-3 essential fatty acids have a positive effect on dry eye.

The DREAM Study—a one-year, double-masked, randomized multicenter study by the National Eye Institute—took a fresh look at the benefits, or lack thereof, of omega-3 supplements in a dry eye patient population.1

The study recruited patients from private and academic optometry and ophthalmology practices throughout the United States.1 Eligible participants included those who had signs and symptoms of moderate-to-severe dry eye on two consecutive examinations performed two weeks apart, dry eye symptoms for at least six months, an Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score ranging from 25 to 80 at a screening visit and an OSDI score ranging from 21 to 80 at the baseline eligibility visit.1 Patients also had to be willing to continue their current dry eye treatment regimens, use or want to use artificial tears at least twice daily in the previous two weeks and have at least two of the following four signs of dry eye in the same eye at the screening and baseline eligibility visits:1

- Conjunctival staining score ≥1

- Corneal fluorescein staining score ≥1

- Tear break-up time (TBUT) ≤7

- Schirmer’s test with anesthesia ≥1mm and ≤7mm in five minutes

|

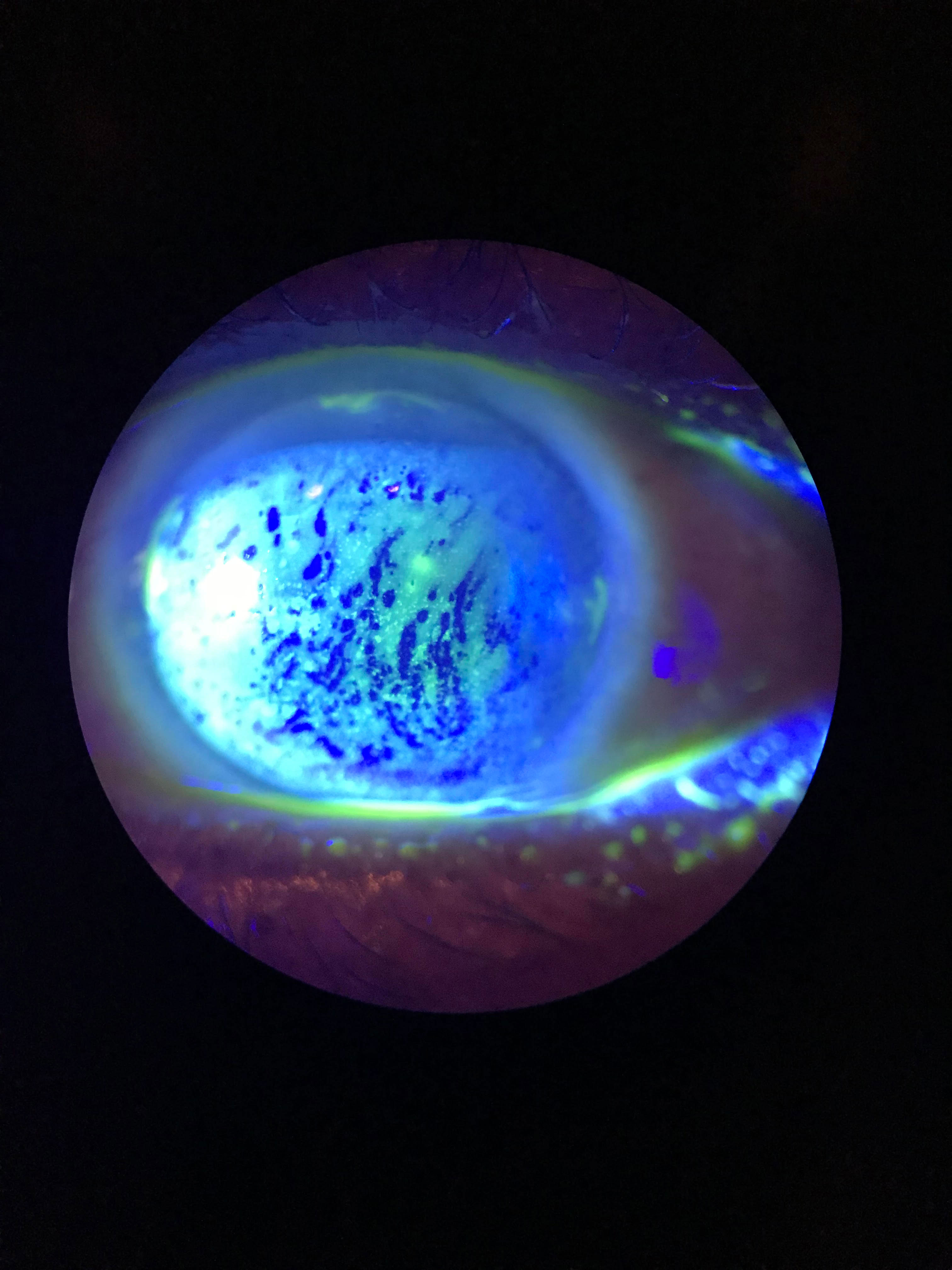

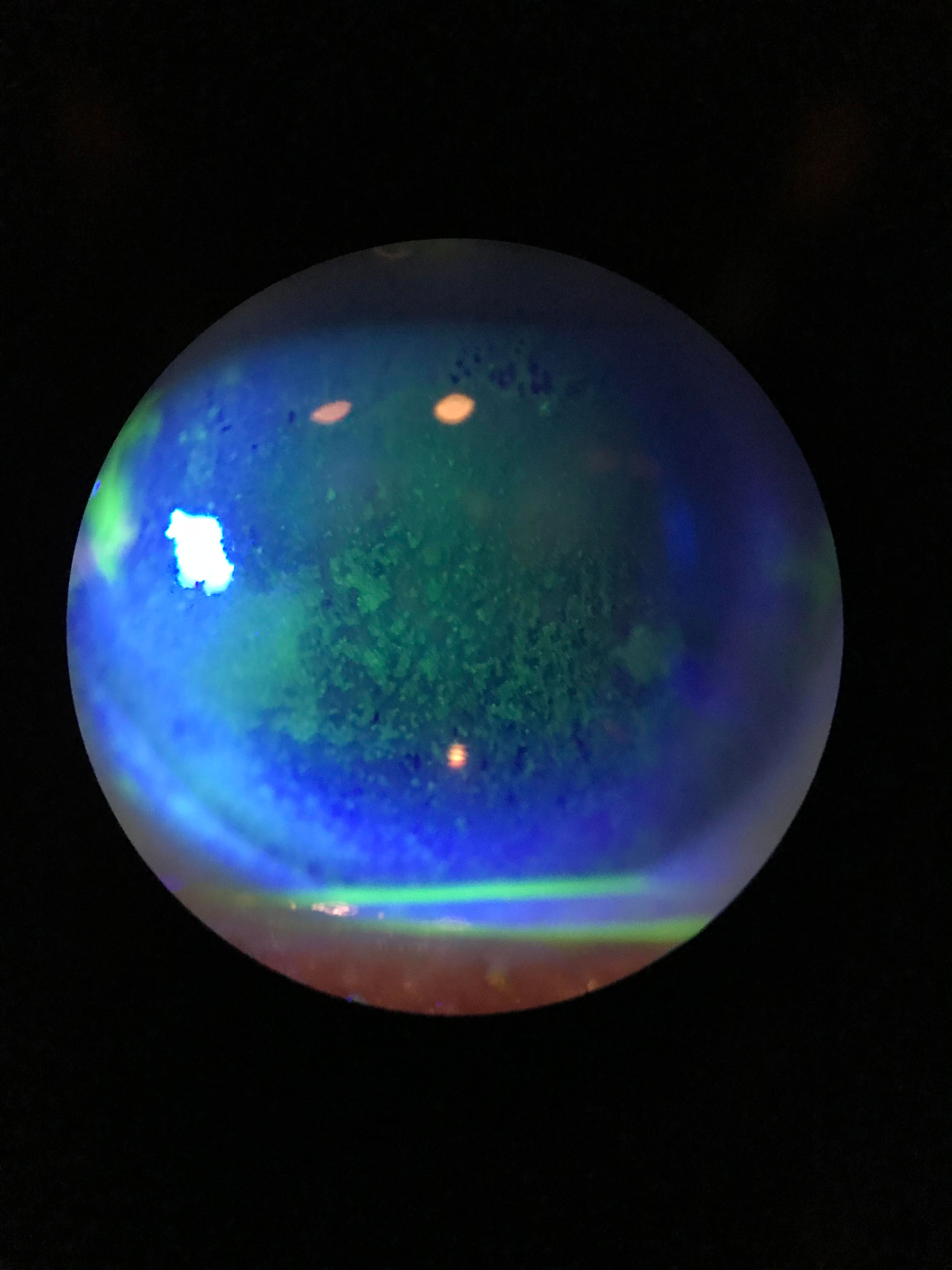

| This patient displays diffuse superficial punctate keratitis (SPK) with a decreased TBUT. Click to enlarge image. Photo: Cecelia Koetting, OD |

Since nutritional supplementation is often used as an adjunct to other dry eye treatments, the inclusion criteria were broad to mimic “real-world” clinical application, says Whitney Hauser, OD, of Southern College of Optometry in Memphis. A total of 329 patients were enrolled in the treatment group and 186 in the placebo group.

The clinical trial was considered “real-world” because it included patients with dry eye disease who sought relief of symptoms despite the use of other interventions. “Patients were allowed to continue their current treatments for dry eye disease, which is not the case in most industry-sponsored trials of treatments for this disease,” the DREAM researchers wrote in their paper.

Additionally, patients with a history of thyroid disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory diseases could be included in the trial if they were otherwise eligible.

The 3000mg daily dosage of n-3 fatty acids was the highest dose used to date in clinical trials of fish-derived n-3 fatty acids.1 The daily placebo was approximately 1tsp of olive oil, which primarily delivered n-9 oleic acid, a substance considered to be neutral with respect to changes in signs and symptoms of dry eye.1

After 12 months, the study authors did not find significant differences in mean OSDI (primary outcome measure) or conjunctival staining, corneal staining, TBUT and Schirmer’s test (secondary outcome measures) between both groups.1

Penny Asbell, MD, who helped conduct the DREAM study, says that because there was no difference between the groups, you can’t conclusively say omega-3 actually works.4 “In fact, some people have said what really worked is seeing [patients] four times a year,” Dr. Asbell suggested in an online interview following release of the study. “Just seeing them seemed to make everybody feel better.” She noted that while dry eye signs and symptoms both improved, the effect was more pronounced among symptoms, which may lend credence to her supposition than the effect was more a subjective experience influenced by the higher level of care provided.

“Within the profession, the study results stimulated a lot of talk and, in my opinion, a return to our scientific roots to read into the study to better understand the methodology and what was really being tested,” says Cecelia Koetting, OD, of Norfolk, VA.

Dr. Anshel notes that the DREAM results also raised a lot of eyebrows in the profession. “Most eye care professionals were surprised at the results of this study since many of them use just omega-3 fish oil to treat dry eye patients and have positive outcomes,” he says.

He adds that he was also slightly surprised omega-3 fell short with how well he usually hears it works for dry eye treatment.

|

| Staining shows this dry eye patient’s diffuse dense superficial punctate keratitis. Click image to enlarge. Photo: Cecelia Koetting, OD |

DREAM Interpretation

In the year since the DREAM study’s release, elements of its methodology have come under fire. In particular, the choice of placebo and whether the olive oil played a confounding role have been under the most intense scrutiny.

“What’s interesting in the study is that both the treatment and placebo groups saw improvements in signs and symptoms of dry eye,” says Mile Brujic, OD, of Bowling Green, OH. He notes that the oils are similar in a way, as they both have strong anti-inflammatory properties.

“It seems that the treatment and the placebo improved outcomes in the study,” Dr. Brujic adds. “Not that the treatment arm didn’t work, but the placebo arm (olive oil) had a strong level of efficacy that met the omega-3’s.”

These results prompt an obvious question: why did the olive oil group do so well?

The olive oil used in the study was refined, meaning it had no significant levels of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory polyphenol compounds, Dr. Karpecki notes. He says oleic acid—an olive oil component and seemingly unlikely placebo candidate—wasn’t incorporated to any significant degree in either group and no other olive oil components offered a plausible explanation on why the placebo group did so well, especially at a dosage of just 1tsp per day.

Compared with the Mediterranean diet (which uses 60g of olive oil), DREAM investigators have suggested the olive oil placebo dose (5g, the equivalent of one tablespoon) was too low to have a therapeutic effect.4,5

“That’s less than you usually put on your salad,” Dr. Asbell noted in her recorded comments.4 “It’s really not comparable to a Mediterranean diet, where it’s 12 times as much per day.” She explained that the study measured blood levels of each group, and found a fourfold increase from baseline in omega-3 levels in the study group but no change in oleic-9 levels among the olive oil users.4

Some critics, however, have fixated on the study’s purported demonstration of a treatment effect from olive oil as a rationale to continue use of omega-3 supplements. “If you want to continue believing that, stop buying omega-3 and tell them to use olive oil,” Dr. Asbell observed in response to the criticism. “It’s a lot less expensive.”4

The researchers defended their choice of placebo by arguing that the anti-inflammatory effects associated with olive oil are attributed mainly to polyphenols not found in the refined olive oil used in the study.6 However, research shows that oleic acid can alter the microbiome and reduce dysbiosis, conferring anti-inflammatory effects elsewhere in the body.6 Oleic acid may also counter the negative impact of saturated fat on the microbiome.7

Dr. Koetting notes that the omega-3 used in the treatment arm was 3000mg of fish-derived n-3 eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids but did not include gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), which has been validated in six dry eye clinical trials for treating dry eye and is an anti-inflammatory omega not found in fish, flax or the average diet.8-13 Given the “real-world” study design, the results of the placebo would have made everything a challenge even if GLA was included and ended up being superior, Dr. Karpecki adds.

“It’s a mystery, but with a p-value of 0.005, I find it hard to believe it could all be a placebo effect,” Dr. Karpecki says. “My only hypothesis is that the ‘real-world’ study design led to murky data, so the dry eye improvements were more due to outside factors that were unaccounted for.”

Further complicating things was the lack of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, Dr. Karpecki notes. Including moderate-to-severe dry eye patients of different demographics and health profiles makes it increasingly difficult to come to a definitive conclusion and say that all oral omegas are ineffective, says Dr. Koetting.

“The study shows that not all omegas perform the same in treating dry eye symptoms,” she notes, “and that olive oil and omegas can both improve dry eye symptoms.”

Dr. Karpecki believes the study did measure a good indicator of dry eye by including osmolarity as an endpoint. He says, however, that unless osmolarity is a factor for enrollment, findings will be too variable and, consequently, inconclusive. And that’s exactly what he thinks happened.

Additionally, while the study was promoted as “real-world,” it assumed most dry eye patients are already using excessive amounts of fish oil, Dr. Anshel notes.

“I have to wonder if the investigators considered the safety of large amounts of omega-3 on a daily basis,” he says, adding that studies have linked excessive omega-3 fatty acids with high blood sugar and other negative side effects.14-16

| DREAM Extension Study Corroborates Original Findings If fish oil therapy had effected a decrease in clinical signs and symptoms in the DREAM study, a worsening of outcomes might be expected following cessation. However, in a follow-up study recently presented at ARVO 2019, the DREAM researchers found no significant difference in outcomes between patients who stopped taking the omega-3 supplements and those who continued taking them over an additional 12-month period. This finding conforms with the original study results of no demonstrable benefit from omega-3 supplementation, the researchers say. The team pulled a subset participants (n=43) from the original treatment arm, randomizing them into two groups: those who continued with therapy (21 patients) and those who switched to the olive oil placebo (22 patients). The primary outcome was a mean change from baseline (month 12 of the primary trial) in Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score. Secondary outcomes included changes in conjunctival and corneal staining scores, tear break-up time (TBUT), Schirmer’s test results and adverse event incidences. After 12 months, the study authors reported that the mean change in the total OSDI score (-0.6 points) was not significantly different between the omega-3 and the placebo groups. Additionally, they did not observe any significant differences between the groups in mean changes from baseline in conjunctival staining scores (-0.5 points), corneal staining scores (-0.6 points), TBUTs (-0.8 seconds) and Schirmer’s test results (1.2mm). They add that the rates of adverse events were also similar between both groups. These latest discoveries are consistent with the results of the primary clinical trial released last year, which also found that there was no beneficial effect of omega-3 relative to olive oil.

|

The Profession Reacts

The DREAM Study did not change Dr. Koetting’s current practice of recommending omega-3 fatty acid supplements to her dry eye patients, and she believes the study’s findings shouldn’t sway others either. “I have found, in practice, that omega supplementation, especially one that is GLA-based, is an effective part of treatment for these patients,” she notes.

The results of the study also haven’t altered Dr. Anshel’s nutraceutical recommendations for dry eye, as he doesn’t use stand-alone omega-3 fish oil as a treatment.

For Dr. Karpecki, the study reinforced the rationale for recommending a GLA (or possibly flaxseed oil/alpha-linolenic acid) along with fish oil. “I think it’s quite notable that the DREAM protocol discusses GLA metabolism and anti-inflammatory pathway at length,” he says.

The DREAM study likely hasn’t had a significant impact on prescribing practices for nutritional supplements in optometry, according to Dr. Hauser. While many would like to dismiss the study based on its design or choice of placebo, she says the results cannot be ignored and it’s possible that nutraceuticals can play a valuable role in dry eye through evolving formulations or the addition of new components. “The study offers an opportunity to talk to patients about their whole food nutrition, which is a conversation many doctors do not have,” Dr. Hauser says.

As a dry eye patient herself, Dr. Hauser continues to take omega-3 supplements and recommends the supplements to her patients. “Doctors committed to omega products use them because they have seen clinical improvement in their patients and believe in the supplements’ anti-inflammatory effects,” she adds. “However, the study does raise the question of whether some patients would have potentially experienced improvement regardless. The DREAM study opened a dialogue about nutrition and supplementation in dry eye. I don’t think it’s the end of the conversation but rather the beginning.”

1. Asbell PA, Maguire MG, Pistilli M. n-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of dry eye disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1681-90. 2. Miljanović B, Trivedi KA, Dana MR, et al. The relationship between dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and clinically diagnosed dry eye syndrome in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(4):887-93. 3. Wojtowicz JC, Butovich I, Uchiyama E, et al. Pilot, prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an omega-3 supplement for dry eye. Cornea. 2011;30(3):308-14. 4. Galor A, Asbell PA. DREAM Study: can omega-3 treat dry eye disease? American Academy of Ophthalmology. www.aao.org/interview/dream-study-can-omega-3-treat-dry-eye-disease. Published 2018. Accessed April 17, 2019. 5. Gorzynik-Debicka M, Przychodzen P, Cappello F, et al. Potential health benefits of olive oil and plant polyphenols. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3). 6. Dennis Ruskin, Julie Poteet, Stuart Richer. Four Great Debates in Ocular Nutrition, Wellness Essentials for Clinical Practice. A Supplement to Review of Optometry. Pages 24-25, Sept. 15, 2018. 7. Alcock J, Lin HC. Fatty acids from diet and microbiota regulate energy metabolism. F1000Res. 2015;4(F1000 Faculty Rev):738. 8. Aragona P, Bucolo C, Spinella R, et al. Systemic omega-6 essential fatty acid treatment and pge1 tear content in Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(12):4474-9. 9. Barabino S, Rolando M, Camicione P, et al. Systemic linoleic and gamma-linolenic acid therapy in dry eye syndrome with an inflammatory component. Cornea. 2003;22(2):97-101. 10. Rashid S, Jin Y, Ecoiffier T, et al. Topical omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids for treatment of dry eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(2):219-25. 11. Macrì A, Giuffrida S, Amico V, et al. Effect of linoleic acid and gamma-linolenic acid on tear production, tear clearance and on the ocular surface after photorefractive keratectomy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241(7):561-6. 12. Brignole-Baudouin F, Baudouin C, Aragona P, et al. A multicentre, double-masked, randomized, controlled trial assessing the effect of oral supplementation of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids on a conjunctival inflammatory marker in dry eye patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(7):e591-7. 13. Sheppard JD Jr., Sing R, McClellan AJ, et al. Long-term supplementation with n-6 and n-3 PUFAs improves moderate-to-severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Cornea. 2013;32(10):1297-304. 14. Brasky TM, Darke AK, Song X, et al. Plasma phospholipid fatty acids and prostate cancer risk in the SELECT trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(15):1132-41. 15. Gow RV, Hibbeln JR. Omega-3 fatty acid and nutrient deficits in adverse neurodevelopment and childhood behaviors. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23(3):555-90. 16. Link R. 8 little-known side effects of too much fish oil. www.healthline.com/nutrition/fish-oil-side-effects. Published July 17, 2018. Accessed April 30, 2019. |