|

In February, a new patient—a 78-year-old female—presented with complaints of sudden onset of blur, in the right eye more so than the left, for the last month. She reported that her vision in the right eye in particular was blurry, “as if I’m looking through something.” She reported that her last ophthalmic examination was approximately a year and a half earlier and her doctor then had reported that everything “was fine.”

Her current medications included simvastatin, atenolol, metformin, Prilosec, Lexapro (escitalopram, Teva), vitamin supplements and ibuprofen. She did not tolerate Lopid (gemfibrozil, Pfizer), she reported.

On gross physical exam, she presented with a cane and guarded ambulation, secondary to a fibular fracture on her right side. She was also casted on her right arm, the result of a pickleball injury during which her leg was also injured. During rehab, she fell again and fractured her right radius.

She had recently moved to the area to be closer to family, but what should have been a positive lifestyle move had morphed into one medical problem after another, and the patient was understandably upset. I’ll get to the relevance of this shortly.

|

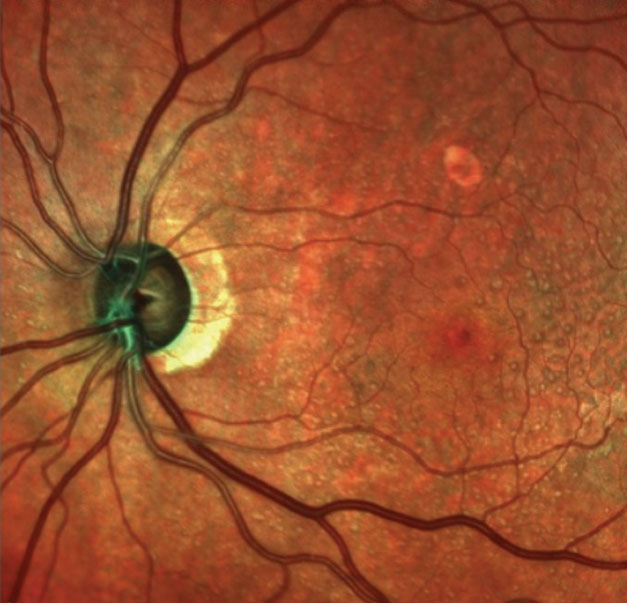

| This multimodal image shows the patient’s left optic nerve. Note the significant neuroretinal rim thinning. |

Diagnostic Data

She was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes 15 to 20 years earlier, with reportedly good control. She was unsure of her last A1c, but reported that her internist was not concerned with the value. She did not check her glucose levels regularly.

Her entering visual acuities were 20/40-2 OD and 20/40 OS through compound hyperopic astigmatic correction. Her best-corrected visual acuities were 20/40 OD and 20/30 OS with minimal refractive change.

Her pupils were equal, round, responsive to light and accommodation with no afferent pupillary defect. Her extraocular muscles were full in all positions of gaze. However, a slit lamp examination of her anterior segments was remarkable for moderate blepharitis in both eyes, with concurrent diffuse staining of the lower corneas. Her angles were wide open, as the patient was pseudophakic. There was no evidence of iris neovascularization in either eye and her applanation tensions were 11mm Hg OD and 12mm Hg OS.

Through dilated pupils, her intraocular lenses (IOLs) were clear and centered in the capsular bags. There was mild posterior capsular opacification in her right eye well off the visual axis, and the posterior capsule of the left eye was opened. Her cup-to-disc ratios were 0.75 x 0.90 OD and 0.6 x 0.80 OS. Her neuroretinal rims were exceedingly thin temporally in both eyes, with significant loss of the rim tissue in the right eye inferotemporally. There was mild bilateral peripapillary atrophy.

Both maculae were characterized by scattered drusen formation and retinal pigment epithelium disruption. No evidence pointed to diabetic macular edema or subretinal neovascular membrane formation. Her retinal vascular examination was consistent with mild hypertensive retinopathy as well as moderate arteriolarsclerotic retinopathy in both eyes. Her peripheral retinal evaluations were unremarkable. No evidence pointed to diabetic retinopathy in either eye.

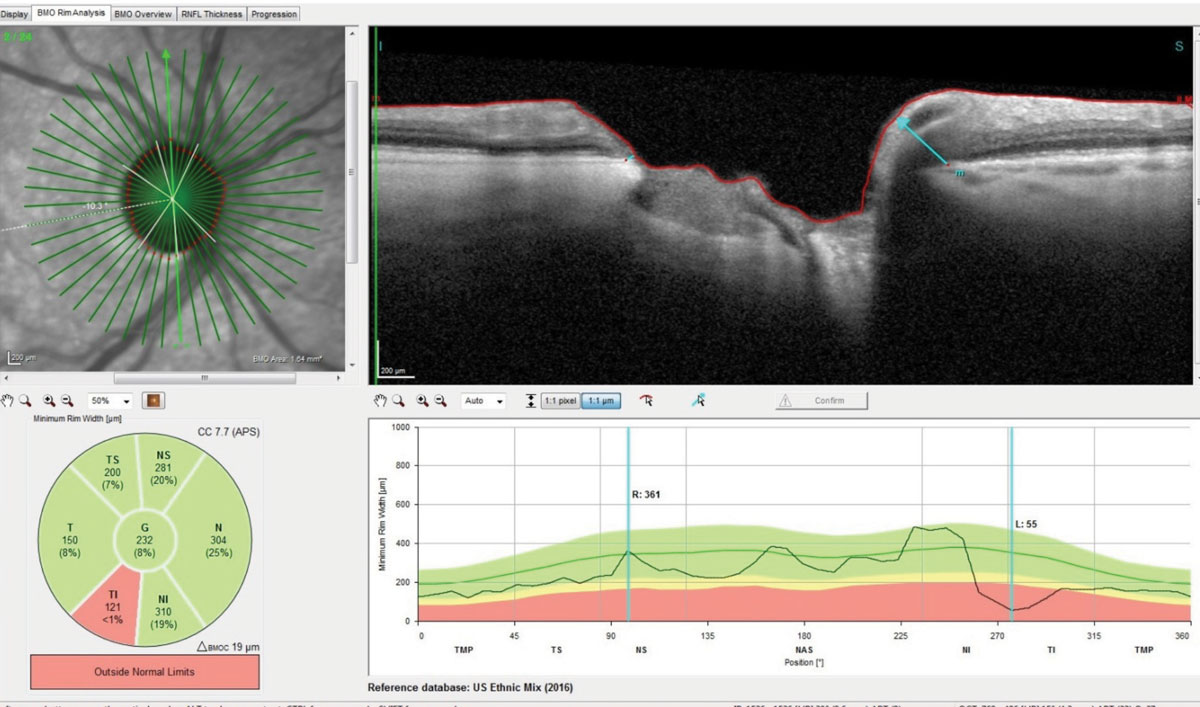

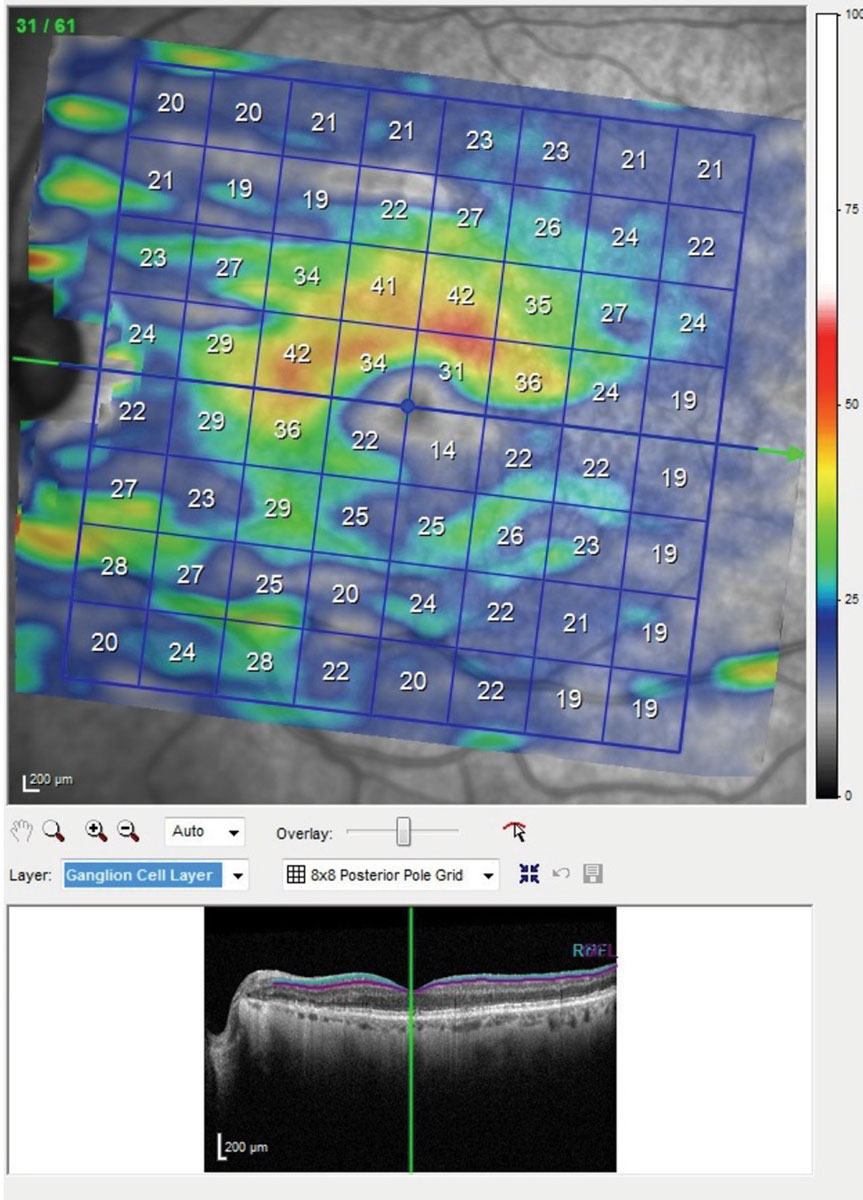

Multicolor laser images of both posterior segments were obtained, as well as optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans of both the optic nerves and maculae. In addition, technicians obtained pachymetry readings. Her central corneal thicknesses were 512µm OD and 503µm OS. The multimodal imaging was consistent with the clinical picture of neuroretinal rim thinning and macular drusen. The OCT imaging of the optic nerves confirmed extraordinarily thin temporal neuroretinal rims and notching, as well as ganglion cell layer loss in both eyes, with loss extending to fixation (more so in the right eye than the left).

|

| This radial set of OCT scans through the right optic nerve demonstrate marked thinning of Bruch’s membrane opening. Note the significant loss of ganglion cells in the inferotemporal rim and a thickness reading of only 55µm in the highlighted scan. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

At the initial visit, it was pretty evident that the patient presented with advanced glaucomatous damage, more so in the right eye than the left. Since this was her first visit with us, and time was limited, we did not have her undergo a threshold visual field test at this visit; rather, it was scheduled for one to two weeks later along with gonioscopic exam of the anterior chamber angles, ultrasonic biomicroscopy and anterior segment OCT imaging of the anterior chamber angles. Given her significant structural damage, as evidenced on the OCTs of both the optic nerves and ganglion cell layers in the maculae, I would expect significant visual field loss in both eyes. In fact, given that the ganglion cell loss extends OU to fixation, I would expect the field defects also to extend to fixation. And this is the most likely etiology of her entering complaint of having difficulty seeing out of the right eye.

This is a straightforward case of how a patient with undiagnosed advanced glaucoma may present to your office and the findings associated with the advanced disease. However, we still have important patient management issues to work out. How do we break this bad news to her, especially given her recent history of two limb fractures, in the context of a disappointing set of circumstances associated with her relocation to the area?

|

| This is the posterior pole map of the ganglion cell layer in the macula of the patients left eye. Though this is the better eye, note the extreme thinning of the ganglion cell layer below the horizontal raphe involving fixation. The same scan of the right eye showed even more damage. With damage to this extent seen structurally, you would expect a superior arcuate visual field defect involving fixation. Click image to enlarge. |

Bedside Manners

Just as every case of glaucoma is different, so too are your patients. The key to delivering this kind of bad news is to get a feel for what kind of patient you are dealing with. I knew from the history that the patient gave, that she was (spiritually) broken. She had moved to a new area to start a new life and instead suffered a series of health mishaps.

But medical information must be delivered openly, honestly and in a manner that you would want to hear if the roles were reversed. I am a straightforward kind of guy. Not all people are like me, but that is who I am.

Knowing that breaking the bad news to an already broken spirit was not going to be pleasant for the patient, I put on my best “I’ve got you covered” tone and laid out the findings to her. “Mrs. Jones, you and I have known each other now for about 10 minutes, and I want to tell you something about me: I’m a straight-shooter when it comes to patient care. You were referred to me because your internist wanted me to evaluate why you weren’t seeing well. I wish I could tell you that this was a simple matter of changing your glasses, but it’s not. For me to imply otherwise would do you a disservice, and I don’t think you want me to do that. I wish it was just a matter of new glasses, but the reason why you’re not seeing well is because my findings indicate that you have glaucoma, and it is affecting both eyes.”

Boom: the bad news was just dropped, but I immediately follow with good news.

“The good news is that we have ways to prevent this from getting worse, and it’s great that Dr. MacDonald referred you this week and not next month. We’ve got great medications and therapies that can help, and this is what we do well. I’ll take good care of you, and we will get through this together.” Now she has an ally in the process and is not alone.

Was she thrilled with the news? Of course not. Was she upset? Yes, but a little hand-holding can go a long way in cases like this. Did she ask why her previous doctor told her “everything was OK”? Yes, she did. And my response there too was positive, explaining simply that her form of glaucoma is hard to diagnose.

Is this the verbiage you should use in your clinic? Not necessarily. This is just a snapshot of what I said in this particular situation. But it was open, honest and delivered in a way I would have wanted to receive news of this kind. As I write this, she is scheduled this afternoon for a follow-up evaluation where her visual fields will most likely demonstrate field loss involving fixation. And she will be greeted with a warm smile, a hand shake/holding and a “how are you doing?” open-ended question.

Delivering bad news is our job. It’s part of managing glaucoma. Pawning off bad news for another provider to deliver is shirking our responsibility as health care providers. Most of what we do is deliver good news, but not always. It may seem counterintuitive, but learning to deliver bad news in a compassionate way makes us better clinicians.