Two of the most protective structures of the ocular system are the conjunctiva and sclera. The conjunctiva, a thin layer of tissue lining the eye and eyelids, contributes to homeostasis of the tear film, provides a layer of protection from foreign material and wards off infection. The sclera, a dense connective tissue made of collagen and elastin, encapsulates the eye, giving it structure and rigidity. Anteriorly, the scleral connects to the cornea at the limbus. Posteriorly, it merges with the meninges at the optic nerve, penetrates the globes and joins with choroidal tissue from the lamina cribrosa.

The integrity of the conjunctiva and sclera is crucial for healthy eyes, and when it is compromised by abnormalities or inflammation, the ocular system quickly becomes chaotic. As primary eye care providers, we often have patients present with symptoms of disorders that affect these structures, and it is our job to provide timely intervention.

This atlas highlights the clinical presentations of some of the most common conjunctival and scleral anomalies so you can quickly identify them in your chair. Prompt diagnosis and treatment will ensure your patients are on the road to recovery in no time.

You will see any number of these issues in your chair, and being able to recognize them quickly will give you a head start on diagnosis and management.

Pinguecula

|

Pinguecula is a common nonmalignant, raised lesion that is most often in the interpalpebral bulbar conjunctiva. This yellowish lesion is a degeneration of elastic tissue and subepithelial collagen with hyalinized connective tissue that does not often involve the cornea. The etiology appears to arise from the effects of environmental elements such as wind, dust and UV light exposure. Research suggests the more common nasal side occurrence is related to the light passing medially through the cornea, which focuses on the nasal limbus, whereas the nose may reduce the intensity of the UV light to the temporal limbus. Other risk factors include age, gender (M>F), smoking, proximity to the equator and diabetes mellitus.3-5 Once the pinguecula is formed, the elevated nature will create symptoms similar to dry eye. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

Pemphigoid

|

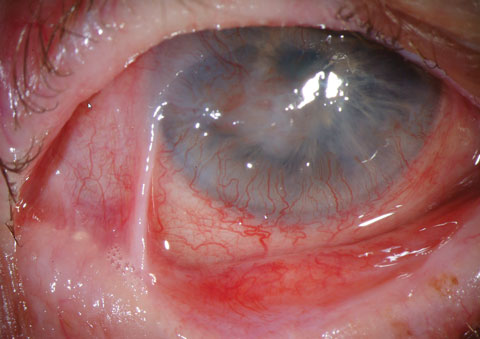

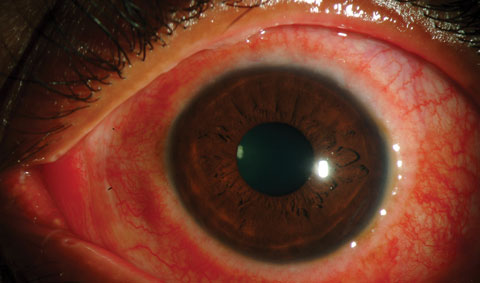

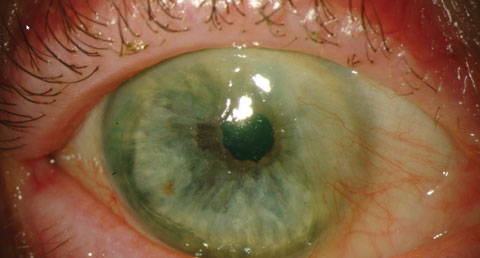

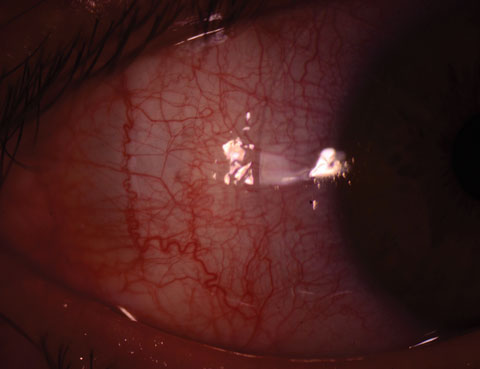

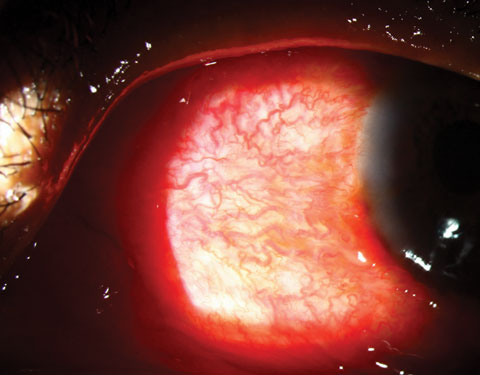

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP), commonly known as a subtype of mucous membrane pemphigoid, is a bilateral, progressive autoimmune conjunctivitis, leading to cicatrization and shrinkage of the conjunctiva with opacification of the cornea. Early symptoms of OCP are hyperemia, discomfort, itching and discharge. However, there are many different stages of this disease, and progression leads to eyelid—most notably trichiasis—and corneal damage and sometimes blindness. The initial presentation of pemphigoid is often a nonspecific hyperemia, and commonly appears as a chronic conjunctivitis or tear reduction. Without discharge in certain quadrants, the condition progresses to: symblephera (adhesions between the tarsal and bulbar conjunctiva); trichiasis; keratoconjunctivitis sicca; corneal neovascularization, opacification and keratinization; and conjunctival shrinkage. The latter represents end stage, with extensive adhesions of the lid to the globe. Chronic corneal epithelial defects can also lead to secondary bacterial ulceration, scarring and, due to restricted movement and opacification of the cornea, loss of sight. The differential diagnosis of progressive conjunctival scarring includes previous radiation exposure and atopic disease. Medicamentosa, sequelae of medical allergic response, can result in a psuedopemphigoid, the clinical appearance of which is identical to that of OCP, but with different causation. The clinical diagnosis of cicatricial pemphigoid is made when there is progression of a symblepharon without a history of local radiation, long-term topical medications or severe perennial allergic conjunctivitis. Photos: Christine Sindt, OD |

|

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis—typically a result of infection, allergy or irritation—is characterized by conjunctival hyperemia, ocular discharge and, depending on the etiology, discomfort and itching. The various etiologies present with differing signs and symptoms, and knowing what to look for will help tailor treatment appropriately:

Viral Conjunctivitis

|

Viral conjunctivitis is often an acute, contagious conjunctival infection usually associated with an infection of the upper respiratory tract or may be related to an adenovirus. Symptoms, which often are limited to one eye at a time, include irritation, photophobia and watery discharge. Conjunctivitis may accompany the common cold and other systemic viral infections, especially measles, but also chickenpox, rubella and mumps. Localized viral conjunctivitis without systemic manifestations usually results from adenoviruses or enteroviruses. Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC), pharyngoconjunctival fever and acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis—a rare conjunctivitis found in Africa and Asia—result from adenovirus serotypes. The virus is often seen with conjunctival hyperemia, watery discharge and ocular irritation, usually beginning in one eye and spreading rapidly to the other. Although the signs may seem common, they vary from patient to patient. Characteristically, follicles may be present on the palpebral conjunctiva, and a preauricular lymph node is often enlarged and painful. Adenoviral conjunctivitis presents with photophobia and foreign body sensation due to corneal involvement. Chemosis, pseudomembranes of fibrin and inflammatory cells on the tarsal conjunctiva, focal corneal inflammation, as well as the subepithelial infiltrates (SEIs) are a direct result of the virus. Corneal opacities occasionally result in decreased vision and significant halos and starbursts. However, extreme redness, light sensitivity and discomfort are the driving symptoms. Even after the conjunctivitis has resolved, SEIs may be visible with a slit lamp, and the threat of dormant virus reactivating the inflammation is common. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

|

Adult Inclusion Conjunctivitis

|

Adult inclusion conjunctivitis is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and has an incubation period of two to 19 days. Most patients have a unilateral mucopurulent discharge, as well as a follicular and hyperemic tarsal conjunctiva response. Preauricular lymph nodes may be swollen on the side of the involved eye. Often, symptoms have been present for weeks or months while nonresponsive to topical antibiotics. A chronic conjunctivitis, mucopurulent discharge, marked tarsal follicular response and failed treatment with topical antibiotics should alert the clinician to the differential of adult inclusion conjunctivitis. Photo: Paul M. Karpecki, OD, and Diana L. Shechtman, OD. |

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

|

Bacterial conjunctivitis is often a byproduct of the natural flora of the individual and is most commonly caused byStaphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia and Haemophilus. Most bacterial conjunctivitis is acute; however, Chlamydia and, rarely, Moraxella may cause a chronic bacterial conjunctivitis. Chlamydial conjunctivitis includes trachoma and adult or neonatal inclusion conjunctivitis. Symptoms are typically unilateral, but frequently spread to the opposite eye within a few days. The bulbar and tarsal conjunctivae can become intensely hyperemic with a mucopurulent discharge. The condition often has a papillary reaction on the palpebral conjunctiva. In cases of adult gonococcal conjunctivitis, symptoms include eyelid edema, chemosis and a prolific purulent discharge. Symptoms of ophthalmia neonatorum secondary to gonococcal infection are bilateral and include intense papillary conjunctivitis with eyelid edema, chemosis and mucopurulent discharge. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

Trachoma

|

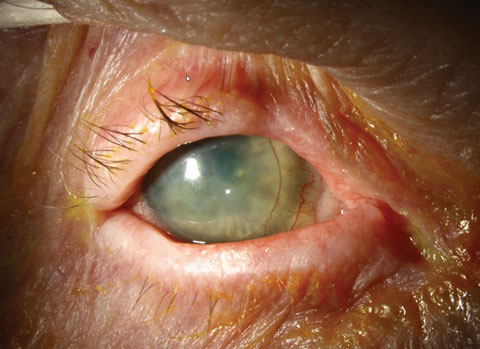

Chlamydia trachomatis, or trachoma, is endemic in poverty-stricken parts of the world, with most blinding occurring in Africa, and rarely occurring among Native Americans and immigrants in the United States. The disease tends to affect children three to six years of age.1 The clinical manifestations are often divided into active disease and those associated with repeat infections. Active disease is symptomatic for a follicular conjunctivitis, and follicles are dome-shaped and the center is avascular. Large follicles located near the cornea may leave depressions known as Herbert’s pits, cicatrial scars of follicles at the limbus, and are considered pathognomonic for trachoma. The active disease will also show signs of papillary hypertrophy and corneal pannus. In contrast, the repeat infections have significant conjunctival scarring, cicatricial entropion with trichiasis and the potential to induce corneal opacification. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

Allergic Conjunctivitis

|

Allergic conjunctivitis is due to a type I hypersensitivity reaction to a specific antigen. Statistics show that more than 50 million Americans suffer from allergies each year.2 Airborne mold spores and the pollen of trees, grasses and weeds cause seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Perennial allergic conjunctivitis (atopic conjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis) is caused by dust mites, animal dander and other nonseasonal allergens. The symptoms of allergy and dry eye tend to overlap; however, patients report bilateral, mild to intense ocular itching, conjunctival hyperemia, photosensitivity, eyelid edema and watery or ropy discharge. Concomitant rhinitis is common. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

|

| Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is a more severe form of conjunctivitis and is most likely allergic in origin. It is most common among males ages five to 20 who also have eczema, asthma or seasonal allergies. Trantas’ dots in the superior limbus represent an aggregation of epithelial cells and eosinophils. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

Pterygium

|

|

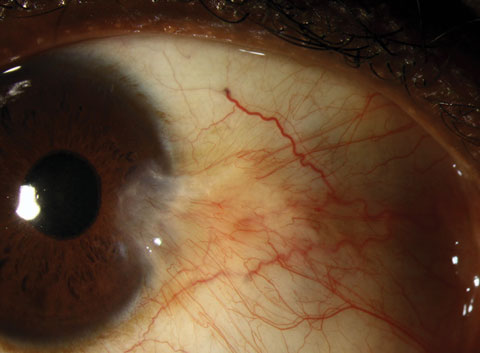

Pterygium is a common conjunctival fibrovascualr lesion originating from the limbus within the palpebral fissure. The nasal limbus is more common for this triangular growth. The growth may spread across the cornea, inducing astigmatism and ultimately affect the visual acuity. The actual etiology of the pterygium is unknown, but a higher incidence is noted in areas closer to the equator or a higher incidence of UV light exposure.6-9 Pterygia are an accumulation of degenerated subepithelial tissue, destroying Bowman’s layer. A slit lamp exam will reveal the typical limbal growth pattern. The thin translucent membrane or thickened, elevated mound may be in the presence of a pinguecula. Because the lesions tend to stay in the interpalpebral zone, lesions resembling a pterygia outside this area are highly suspicious. Photos: Christine Sindt, OD. |

|

Episcleritis

|

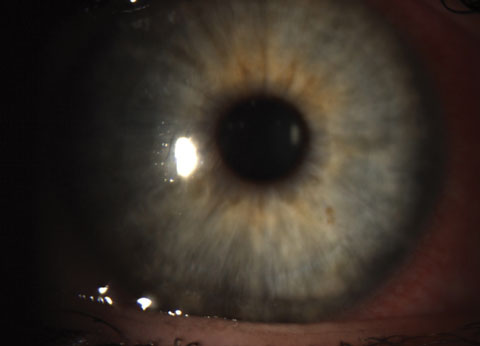

Episcleritis is an idiopathic inflammation of the episcleral tissue and occurs in young adults, more commonly among women.10 It is usually idiopathic and can be associated with connective tissue diseases and, rarely, with serious systemic diseases.11 Episcleritis is classified as either nodular or simple. Nodular episcleritis has discrete, elevated areas of inflammation; simple episcleritis is present without nodules. Episcleritis is distinguished from conjunctivitis by hyperemia localized to a limited sector or diffuse areas of the globe, much less lacrimation and no discharge. It is distinguished from scleritis by lack of photophobia and lack of severe pain. The condition is often described as self-limited, and a diagnostic assessment for systemic disorders is not routinely warranted. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

Scleritis

|

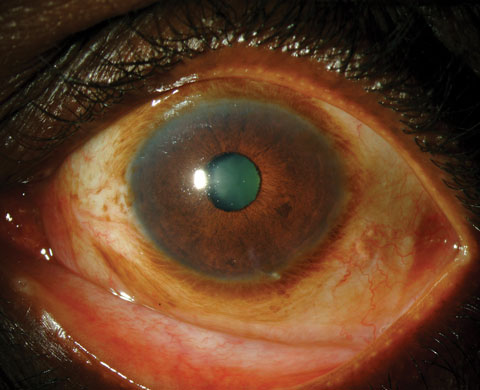

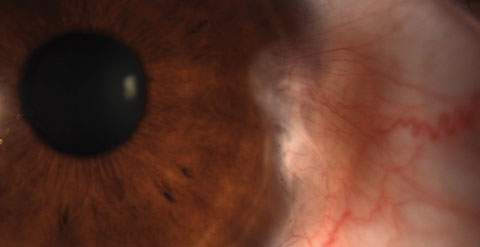

Scleritis is a destructive, vision-threatening inflammation involving the deep episclera and sclera. Fourteen percent of patients with scleritis lose significant visual acuity within a year, and 30% lose significant visual acuity within three years.12 Scleritis is most common in females in their third to fifth decade, many of whom have connective tissue diseases.12 About half of the cases of scleritis have no known cause. Symptoms are moderate to marked pain, hyperemia of the globe, tearing and light sensitivity. Scleritis most commonly involves the anterior segment and occurs in three types: diffuse, nodular and necrotizing. Pain, often characterized as a deep, boring ache, is often severe enough to interfere with sleep and appetite. Hyperemic patches develop deep beneath the bulbar conjunctiva and with a more violet color compared with those of episcleritis or conjunctivitis. The involved area may be focal (usually one quadrant of the globe) or involve the entire globe and may contain a hyperemic, edematous, raised nodule (nodular scleritis) or an avascular area (necrotizing scleritis). Posterior scleritis is less common and is less likely to cause red eye but more likely to cause blurred or decreased vision. In severe cases of necrotizing scleritis, perforation of the globe and loss of the eye may result. Necrotizing scleritis in patients with connective tissue disease signals underlying systemic vasculitis. Patients with necrotizing scleritis and underlying systemic vasculitis have a mortality rate mostly due to myocardial infarction. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. |

Conjunctivochalasis

|

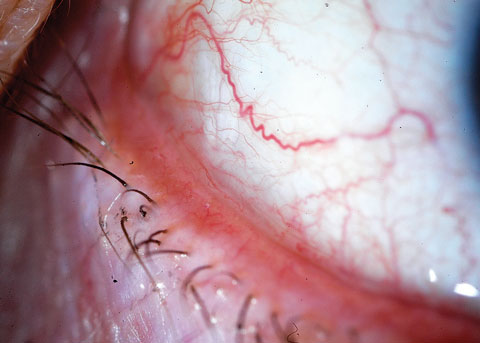

Most conjunctivochalasis is thought to be caused by the gradual thinning and stretching of the conjunctiva that accompanies age as well as a loss of adhesion between the conjunctiva and underlying sclera related to the dissolution of Tenon's capsule. The resulting loose, excess conjunctiva may mechanically irritate the eye and disrupt the tear film and its outflow, leading to dry eye and excess tearing. A correlation may also exist between inflammation in the eye and conjunctivochalasis; however, it is unclear if this correlation is causal. Conjunctivochalasis may be associated with previous surgery, blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) and aqueous tear deficiency. Symptoms range from dry eye, epiphora and irritation to localized pain, foreign body sensation, subconjunctival hemorrhage and ulceration. Symptoms often worsen due to vigorous blinking. |

|

| Photo: John P. Herman, OD. |

Dr. Bloomenstein is director of optometric services at Schwartz Laser Eye Center in Scottsdale, Ariz.

|

1. International Trachoma Initiative. The world’s leading cause of preventable blindness. Available at http://trachoma.org/about-trachoma. Accessed Sept. 13, 2016. 2. American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Allergy Facts. Available at http://acaai.org/news/facts-statistics/allergies. Accessed September 13, 2016. 3. Ozer PA, Altiparmak UE, Yalniz Z, et al. Prevalence of Pinguecula and Pterygium in Patients With Thyroid Orbitopathy. Cornea. 2010;29(6):659-63. 4. Yam JC, Kwok AK. Ultraviolet light and ocular diseases. Int Ophthalmol. 2013 May:14(2)187-94. 5. Mimura T, Obata H, Usui T, et al. Pinguecula and diabetes mellitus. Cornea. 2012 Mar;31(3):264-8. 6. Moran DJ, Hollows FC. Pterygium and ultraviolet radiation: A positive correlation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:343-6. 7. Taylor HR, West S, Munoz B, et al. The long-term effects of visible light on the eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:99-104. 8. Ang LP, Chua JL, Tan DT. Current concepts and techniques in pterygium treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:308-13. 9. Singh G. Pterygium in the tropics. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(5):542-3. 10. Homayounfar G, Nardone N, Borkar DS, et al. Incidence of Scleritis and Episcleritis: Results From the Pacific Ocular Inflammation Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013 Oct;156(4):752-8. 11. Akpek EK, Uy H, Christen W, et al. Severity of episcleritis and systemic disease association. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(4):729-31. 12. Roque MR. Scleritis. Medscape. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1228324-overview#a6. Accessed September 13, 2016. |