|

Symptoms of headache concurrent with clinical findings of bilateral optic disc edema are of serious concern. Papilledema is optic disc swelling due to high intracranial pressure (ICP). Its causative conditions can include hydrocephalus, spinal cord lesions, cerebral sinus drainage impairment, intracerebral mass, cerebral hemorrhage, meningitis and idiopathic intracranial hypertension (Table 1).

Visual function loss is the feared morbidity of papilledema. Treatment is directed at the underlying cause of the high ICP, and options include both medical and surgical modalities.

A thorough neuro-ophthalmic workup helps the clinician sort through the myriad differential diagnoses, which can include Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). This is an acute polyneuropathy in which the immune system attacks myelin within the peripheral nervous system. GBS manifests as an acute inflammatory neuropathy with weakness and diminished reflexes. Patients initially experience numbness and tingling in their extremities. The condition may progress, eventually resulting in paralysis.1,2

Case Example

While on active military duty, a 19-year-old Asian male experienced sudden numbness and loss of sensation in his lower extremities, causing him to fall down the stairs at his barracks. Prior to this episode, he was in excellent health without any medical conditions. He did, however, receive a flu vaccination a few weeks prior to his symptoms. He was immediately admitted to the hospital, where neuroimaging was performed and a lumbar puncture and serologic testing confirmed a diagnosis of GBS. Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment was initiated and a plasmapheresis (plasma exchange) was also completed.

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Bilateral Disc Edema

|

The patient presented for an eye examination two months following his GBS diagnosis. He was now wheelchair bound. The patient had no visual or ocular complaints, though he reported occasional generalized headaches of low intensity. The patient was taking amitriptyline 100mg QHS, gabapentin 600mg TID, morphine ER 15mg QHS and metoprolol 25mg BID.

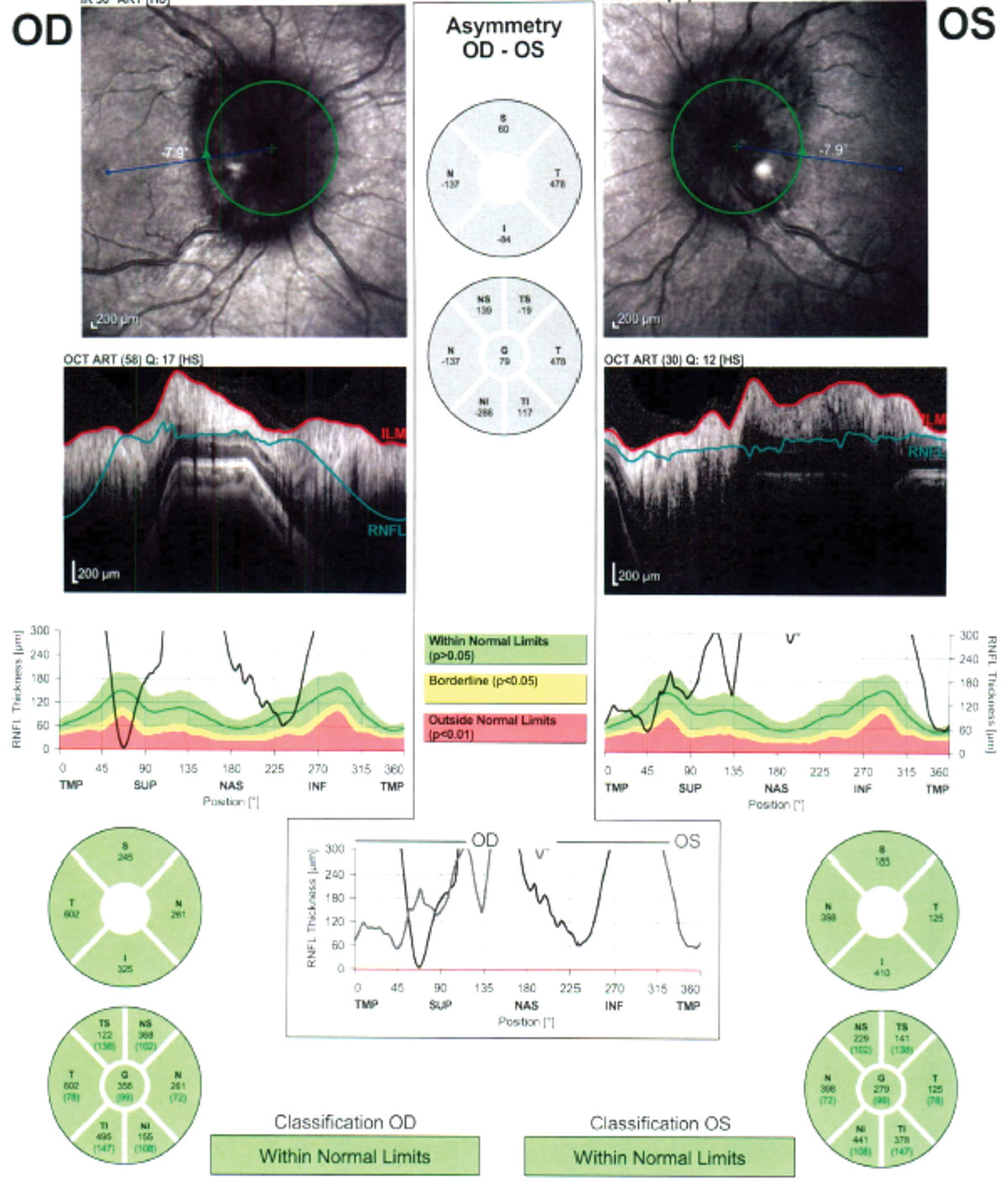

His best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 OD and OS and all other preliminary findings were unremarkable. Posterior segment evaluation revealed bilateral small optic cups with 3+ optic disc edema OD and OS. A splinter hemorrhage was detected temporal to the disc OD. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) revealed thickening of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) OD and OS (Figure 1). A Humphrey 24-2 visual field revealed enlarged blind spots in both eyes.

The patient was diagnosed with bilateral disc edema. We ordered an MRI of the brain and orbits, with and without contrast, as well as targeted serologic workup.

The MRI revealed nonspecific T2/FLAIR hyperintense foci within the right frontal white matter. These lesions may result from migraine, demyelination or inflammation. No other intracranial or intraorbital abnormalities were detected. Serology was negative for HIV, syphilis, Lyme disease and neuronal antibodies. Copper levels and serum protein electrophoresis were within normal limits.

Lumbar puncture showed an elevated opening pressure of 40cm H2O (the normal range for adults is 10cm to 20cm H2O). The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed elevated protein levels. The patient was diagnosed with papilledema associated with GBS. He was prescribed 500mg acetazolamide BID PO. Following treatment, the patient’s papilledema gradually began to resolve.

GBS: The Basics

GBS occurs more often in females (1.5:1) and its risk tends to increase with age. Ever since the eradication of polio, GBS has been the leading cause of acute paralytic disease within the western world.1,2 Researchers speculate it is triggered by a viral infection, as approximately 60% to 70% of people with GBS had a preceding infection, most commonly gastroenteritis or an upper respiratory infection. Studies have also linked GBS and the flu vaccination, but have yet to establish causation. GBS frequency rose in 1976 and 1977 during the mass immunization campaign against the swine flu. However, no subsequent vaccines have been associated with an increased incidence of GBS.1,2

|

| Fig. 1. SD-OCT revealed peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickening in both eyes. Click image to enlarge. |

GBS develops over the course of a few days to a month. Early symptoms include numbness, tingling and weakness in the extremities. Later, paresthesia, quadriplegia and hyporeflexia can occur.3 Approximately 15% of cases develop weakness in the muscles required for breathing. Diagnosis is made based on a combination of electrophysiological studies demonstrating slowed or blocked nerve conduction and CSF protein level testing. Glycolipid antibodies are observed in the sera of 60% to 70% of GBS patients during the acute phase, with gangliosides being the major target antigens.

Therapy aims to eliminate symptoms and speed recovery with immunoglobulin therapy, plasma exchange or a combination.1-3

GBS and The Eye

Ophthalmic manifestations of GBS include oculomotor palsy (which occurs in 10% of patients), accommodative dysfunction, optic neuritis and true papilledema, although the latter is exceedingly rare in GBS.2,4 Approximately 80% to 90% of patients with papilledema first seek treatment for a headache.5 In this case, our patient only mentioned occasional, mild headaches. However, the morphine may have been masking their intensity.

Other ocular symptoms and signs in papilledema secondary to GBS may include reduced visual acuity, enlarged blind spot, transient visual obscurations and diplopia secondary to a sixth cranial nerve palsy.6 MRI with concomitant magnetic resonance venography (MRV) to rule out venous sinus thrombosis are the preferred neuroimaging studies for bilateral disc edema.

Although research does not widely report ICP with GBS, the increased ICP has been associated with an elevated CSF protein level—common in GBS.7 Investigators hypothesize that the increased CSF protein decreases the rate of reabsorption of CSF through the brain’s arachnoid granulations, leading to increased ICP.8 CSF protein concentration is one of the main factors to consider in differentiating papilledema associated with GBS from idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Treatment of papilledema involves addressing the underlying cause, as well as lowering the ICP. First-line treatment is usually a diuretic drug such as acetazolamide. If medical treatment is insufficient, serial lumbar punctures may be beneficial in providing temporarily relief from symptoms of intracranial hypertension. Other more invasive therapies such as a ventriculoperitoneal shunt or optic nerve sheath fenestration may be necessary in severe cases.4

Patients with GBS may present to the optometrist with ocular manifestations, including true papilledema. In any case of bilateral disc edema, clinicians should comanage with neuro-ophthalmology to rule out serious threats to vision and life. MRI, MRV, serum analysis and, if indicated, lumbar puncture with CSF analysis, can help uncover the underlying cause.

Dr. Bishop, a graduate of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry with an advanced studies certificate in neuro-ophthalmic disease, is completing a residency in brain injury vision rehabilitation/ocular disease at the Audie L. Murphy Memorial VA Hospital in San Antonio.

Dr. Fox is the eye care provider at the Polytrauma Rehabilitation Center of Texas at the Audie L. Murphy Memorial VA Hospital in San Antonio. Her area of specialty is low vision rehabilitation with an emphasis on neuro rehabilitation.

|

1. van Doorn PA. Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). Presse Med. 2013 Jun;42(6 Pt 2):e193-201. 2. Alrohimi A, Ba F. Headache and papilledema in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Canadian J Neurol Sci. 2018;42(3):351-53. 3. Gurwood AS, Drake J. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Optometry. 2006;77(11):540-46. 4. Rigi M, Almarzouqi SJ, Morgan ML, Lee AG. Papilledema: epidemiology, etiology, and clinical management.” Eye Brain. 2015 Aug;7:47-57. 5. Sadun AA, Wang YM. Papilledema and raised intracranial pressure. In: Levin LA, Albert DM. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010:883-86. 6. Farmakidis C, Inan S, Milstein M, Herskovitz S. Headache and pain in Guillain-Barré syndrome.” Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015;19(8):40. 7. Zhao PP, Ji QK, Sui RB, et al. Increased intracranial pressure in Guillain-Barré syndrome: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(30):e11584. 8. Gardner WJ, Spitler DK, Whitten C. Increased intracranial pressure caused by increased protein content in the cerebrospinal fluid. N Engl J Med. 1954;250(22):932-6. |