|

A 34-year-old Hispanic female presented with symptoms of hazy vision and floaters in her left eye for a few months. The eye was not red and she denied having any pain or discomfort. The right eye was unaffected. She reported good general health and had no prior ocular problems. She was not nursing or pregnant.

Upon examination, her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 OD and 20/30 OS. Confrontation visual fields were full to careful finger counting OU and ocular motilities were normal.

Her pupils were equal, round and reactive to light with no afferent pupillary defect. The right eye was completely normal. The left eye showed trace cell, but was otherwise normal.

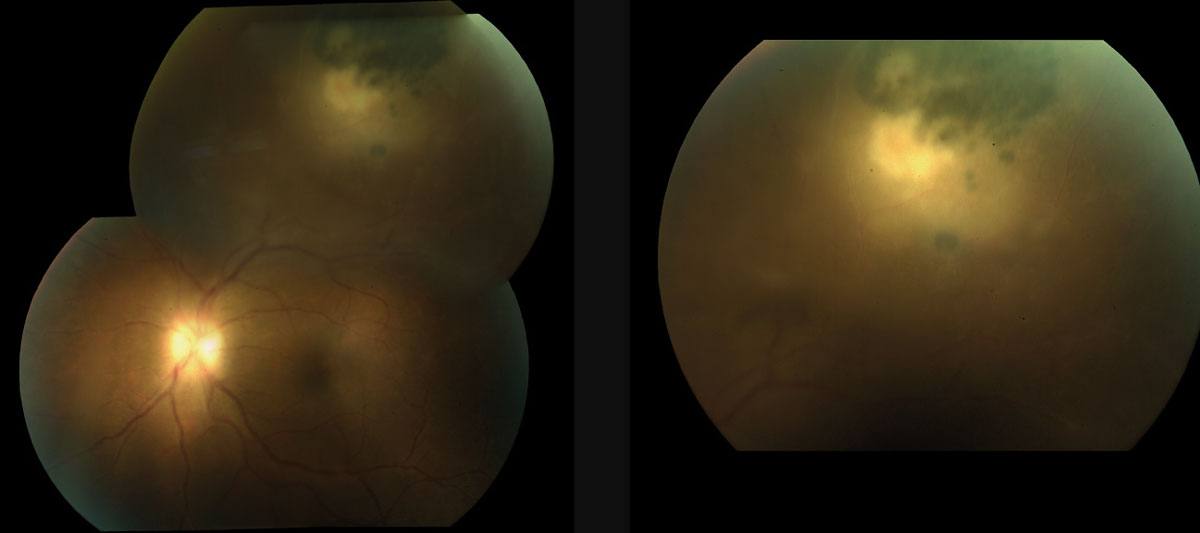

On dilated fundus exam, the right eye was unremarkable. The vitreous of the left eye had 2+ vitreous cells. The exam did reveal some other changes (Figure 1). An SD-OCT of the macula in the left eye was normal.

|

| Fig. 1. Can this 34-year-old patient’s fundus images explain anything about her hazy vision and influx of floaters? |

Take the Quiz

1. What does the fluffy white lesion represent?

a. Myelinated nerve fiber (MNF).

b. Cotton wool spot.

c. Active retinochoroiditis.

d. Chorioretinal scar.

2. What is the correct diagnosis for the fundus lesion?

a. Active syphilis.

b. Toxocara canis.

c. Toxoplasmosis.

d. Histoplasmosis.

3. What is the treatment for this patient?

a. Bactrim PO, clindamycin PO, steroids PO, folic acid.

b. Azithromycin PO.

c. Doxycycline PO.

d. Observation.

4. What additional testing would be most helpful in making the correct diagnosis?

a. Elisa blood test for IgG and IgM.

b. Blood test for FTA-ABS, RPR.

c. PPD.

d. HLA-B27, HLA-A29.

5. Which statement best character-izes her condition?

a. Likely acquired.

b. Likely congenital.

c. Reactivation.

d. Autoimmune.

For answers, see below.

Discussion

Our patient presented with symptoms of hazy vision with an increase in floaters. These symptoms are due to the vitreous cells that were seen on her clinical exam once she was dilated. She also has a fluffy-white lesion superotemporal that is adjacent to a pigmented chorioretinal scar. This is a classic presentation of active toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis. Because it is adjacent to the pigmented chorioretinal scar, this likely represents reactivation of a previous infection.

Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of posterior uveitis and accounts for approximately 90% of focal necrotizing retinitis.1 It is caused by an intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii.1 Cats are the definitive hosts for Toxoplasma gondii, and humans and other mammals act as intermediate hosts. T. gondii exists in three forms, all of which are able to infect its hosts. Tachyzoites can infect almost all leated cells through a process of active invasion. Tissue cysts, which contain the bradyzoites, are the dormant form and primarily found in the brain and skeletal muscles. Oocysts are produced during the sexual cycle that takes place in the intestine of acutely infected felines.

The transmission occurs by many routes, including ingestion of raw or undercooked meat infected with tissue cysts, ingestion of food and water contaminated with oocysts, ingestion of eggs and milk contaminated with tachyzoites, blood transfusion, organ transplantation or transplacental transmission.

The most common form of transmission of the disease is mother to child, transplacentally. Mothers who are seropositive for toxoplasmosis show rates of transmission between 60% and 81%, often noticeable in the third trimester.2 Manifestations of congenital toxoplasmosis include: hydrocephalus, seizures, intracranial calcifications, and retinochoroiditis. Pregnant mothers are cautioned to avoid con-tact or exposure to litter boxes.

|

| Fig. 2. This fundus image shows our patient three years after her initial presentation. She was able to resolve on her own without treatment. |

Making the Call

The diagnosis toxoplasmosis is usually made based on the clinical presentation. Serologic blood studies such as the Toxoplasma ELISA can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Detection of IgM antibody titers are present within the first two weeks of infection and suggests a recently acquired infection. IgG antibodies means they were exposed to the infection some time in their life time. The IgG antibodies are produced within two weeks and peak at two months and will be present for life.

Interestingly, a positive toxoplasmosis titer doesn’t always ensure that the diagnosis of a lesion in the eye is from toxoplasmosis. This is because there is a high seropositivity in the general population. In fact, more than 60 million people in the United States may have been affected with the parasite, but those who have been affected have few symptoms, if any.3 This is because a healthy person’s immune system usually keeps the parasite from causing illness. A negative titer should give strong deliberation to alternate diagnosis.2 Blood work up was not performed on our patient because it was a pretty “classic” presentation.

Toxoplasmosis is generally self-limiting in immunocompetent patients and will resolve spontaneously in four to eight weeks. Treatment is reserved for lesions threatening or involving the macular or optic nerve or if there is a significant reduction in visual acuity due to a severe vitritis. Other indications for treatment include an active lesion greater than one disc diameter in size and /or any immunocompromised patient.1-2 Peripheral lesions that do not affect visual acuity generally can be carefully followed without treatment.

Treatment

The standard for treating active toxoplasmosis patient is clindamycin 30mg PO TID, Bactrim DS PO BID, and prednisolone 40mg PO QD. This is referred to as “triple-therapy.” Some uveitis specialists will also give an intravitreal injection of dexamethasone 0.4mg/clindamycin 1mg. This is considered quadruple therapy.4

In one study of 68 patients with active toxoplasmosis, investigators compared the standard triple-therapy (34 patients) with local therapy with only an intravitreal injection of clindamycin and dexamethasone (34 patients) and found both groups of patients did equally well. They concluded that this might be an acceptable alternative to the clas-sic triple-drug treatment in ocular toxoplasmosis.

Advantages of intravitreal treatment include convenience, improved systemic side effect pro-file, greater availability and fewer follow-up visits and hematological evaluations.5

Azithromycin has also emerged as an alternative treatment for toxoplasmosis. Research compar-ing traditional triple therapy with azithromycin shows no significant difference in results.6

Our patient did not admit to having any cats nor eating any raw or undercooked pork, lamb or venison. She was observed with-out treatment and spontaneously resolved on her own.

Retina Quiz Answers:

1) c; 2) c; 3) d; 4) a; 5) c.

1. Yanhoff N, Duker J. Uveitis and Other Intraocular Inflammations” Ophthalmology: Expert consult, 3rd edition. Mosby November 2008; 828-831. |