|

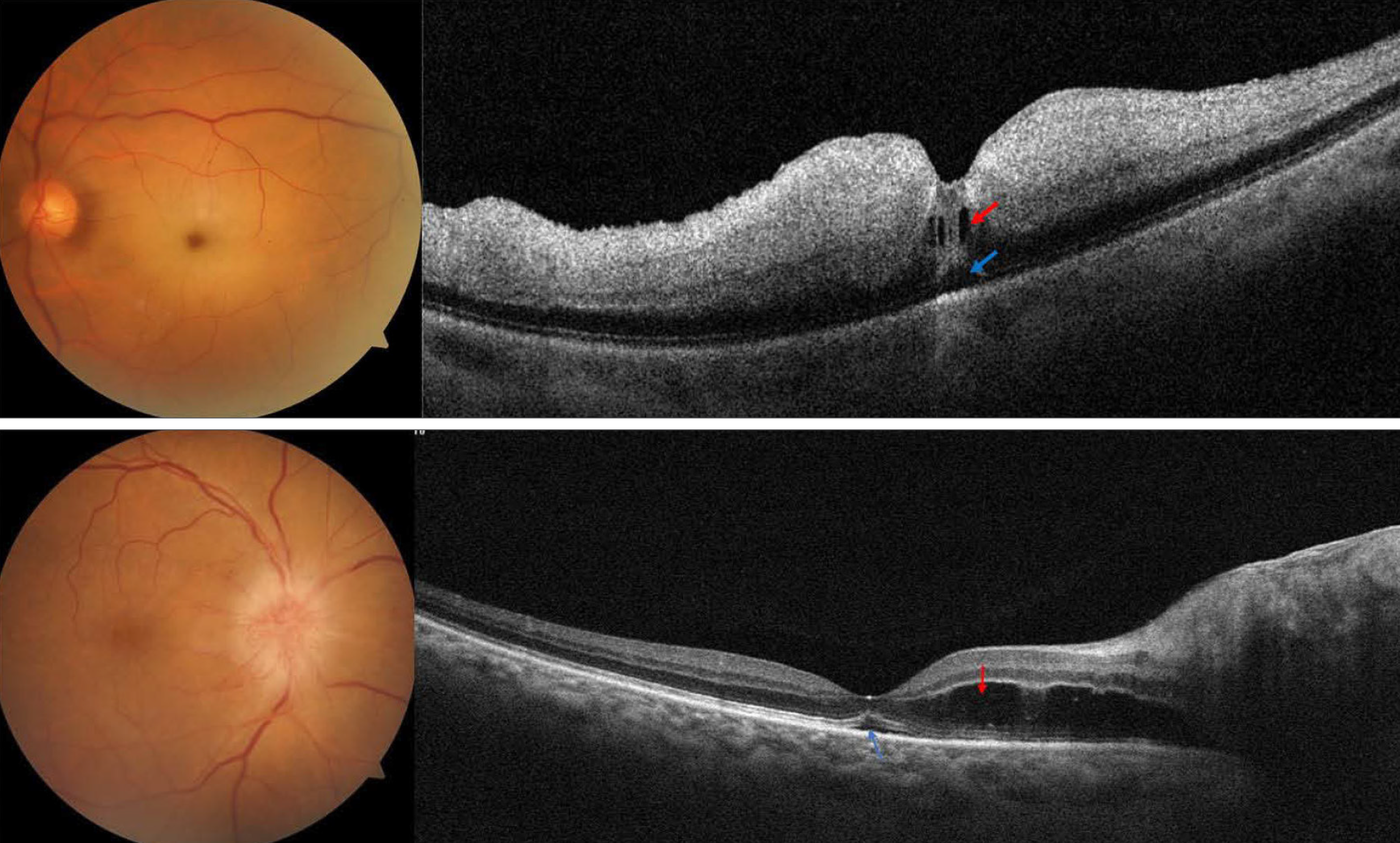

| Representative cases of macular fluid in acute central retinal artery occlusion (top) and acute non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, from the study. Evidence of intraretinal fluid (red arrow) and subretinal fluid (blue arrow) is noted in each case. Photo: Fouad YA, Hamza MN, Wessam MM. Clin Ophthalmol. March 21, 2024. Click image to enlarge. |

Fluid detection on macular OCT most often raises suspicion for retinal vein occlusion. Other potential areas of interest involve macular fluid’s connection with acute infarction of the retina or optic nerve head. Consequently, one group of researchers examined both the prevalence and distribution of fluid within a cohort of eyes with either acute central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) or non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) using OCT.

Included in the small retrospective study were 16 eyes with acute CRAO and 11 eyes with acute AION, of which all patients had no comorbidities known to cause macular fluid. Of eyes with CRAO, fluid was seen in 31%. This was mainly subretinal or intraretinal located within the outer retinal layers, both of which categories included three separately affected eyes. Only one eye displayed inner retinal cysts.

Fluid was present in 73% of eyes with acute AION, with subretinal fluid noted in four eyes and extended into the foveal area in three of these. Outer retinal cysts were discovered in six eyes, while inner retinal cysts were seen in three. No eyes showed hard exudate deposition. A small subset of eyes with CRAO and macular fluid were followed-up with, and of that category, visual acuity improved, while eyes with AION retained stable visual acuity.

Upon their findings, the study authors indicate that “fluid is an understudied feature of retinal and ONH infarction and may have a role in predicting neuronal damage extent and visual outcome.”

In their discussion, the authors further elaborate that macular edema associated with acute CRAO has been suggested for a while to be distinct from other retinal vascular disorders presenting edema, like diabetic retinopathy. It is thought as being intracellular swelling rather than extracellular fluid accumulation.

Further elaborated on are the potential reasons for subretinal fluid being present with AION. Possible pathophysiological mechanisms may include ischemic breakdown of the inner blood-retinal barrier with fluid leakage exceeding the capacity of removal by the retinal pigment epithelium, venous return impairment or Muller cell dysfunction. What’s more, this type of fluid is likely a transudate than an exudate because no hard exudates are deposited in association, which was found in this cohort.

The results of this investigation urge the importance of the need for identifying biomarkers for CRAO, as biomarkers offer a way to stratify patients and determine who may benefit from certain interventions.

Related to this, the authors posit that “fluid leakage in eyes with acute CRAO and AION likely represents a feature of neuronal damage with blood-retinal barrier breakdown and understanding the implications of fluid accumulation and its distribution might help in understanding the extent of damage and in counseling the patients about their visual prognosis.”

Fouad YA, Hamza MN, Wessam MM. Prevalence and distribution of macular fluid with central retinal artery occlusion and anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Clin Ophthalmol. March 21, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. |